The oil fields on Signal Hill above Long Beach were so densely dotted with derricks, people started calling it "Porcupine Hill."

Thankfully, we've got a better view now.

circa 2013

These Long Beach Unit islands are known as THUMS, an acronym for the collective of oil companies that partnered to tackle the enormous Wilmington Oil Field—first discovered 1936 and extended to the east in 1961, making it one of the largest such fields in the continental U.S.

They are:

But the "THUMS" entity was later purchased by ARCO and, in 2000, Occidental Petroleum, the predecessor to California Resources Corporation.

Because of its proximity to both Long Beach and the Los Angeles harbor neighborhood of Wilmington, it requires some cooperation between both cities—which includes inviting community stakeholders onto the islands for occasional tours.

Living in Beverly Hills, I've never had the chance to visit any of the THUMS islands, until Long Beach Architecture Week hosted a tour—and I got to cross this adventure off my bucket list.

Constructed in 1965 out of 640,000 tons of boulders from Catalina Island and over 3 million cubic yards of sand (dredged from the harbor bottom), the 10-acre "oil islands" took two years to complete. The closest one is Island Grissom, followed by Island White—named in memoriam of Gus Grissom and Ed White, U.S. astronauts who, alongside another island namesake Roger Chaffee, died in the first Apollo mission.

A fourth island, which actually clocks in at 12 acres, is named after another lost astronaut—the first fatality among the NASA Astronaut Corps, Ted Freeman. That explains how the THUMS islands got their other nickname—"Astronaut Islands." It's a fitting tribute, considering Long Beach's aerospace legacy—and it's an improvement over their original names (Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, and Delta), which only lasted until 1967.

The original idea behind the construction of the islands was to beautify the shoreline and provide some escapism in an otherwise industrial setting. This was just 10 years after Disneyland first opened, and the timing coincided with the optimistic futurism of the 1964/65 World's Fair in New York City—so, it's no wonder that theme park designer Joseph H. Linesch (of the firm Linesch and Reynolds, with his partner Horace E. Reynolds) was chosen to help design the project.

Linesch had already disguised a Venice derrick as a lighthouse and a Beverly Hills one as an office building. On the islands, he ended up camouflaging the oil drilling rigs with "condo-style" soundproof towers that rise 178 feet up out of a thematic landscape that appears to be recreational.

Traveling to one of the islands by boat feels not altogether different from riding the Jungle Cruise at Disneyland, and disembarking somewhat mimics an arrival to Tom Sawyer Island. Then again, Linesch had worked on some landscapes at Walt's theme park, including those of Adventureland, as well as Busch Gardens.

The tropical plantings—from palm trees to bougainvillea—were his idea. They don't really help the islands blend in, per se. But it's not the tiki-fied "South Seas" approach that the City of Long Beach originally wanted, either.

The creation of the entire "fantasy island" environment—replete with waterfalls and concrete "sculptures"—was a team effort that also included architectural sculptor Herbert J. Goldman and Santa Monica's own landscaper, Morgan "Bill" Evans (who'd helped execute Linesch's Disneyland plans with his brother, Jack Evans).

The concrete facades aren't just strangely beautiful in a space-age kind of way (especially when they're lit up in colors at night) but also functional. They help block the drilling noise from reaching the shore—especially since the work never ceases on the island, with operations running 24/7, 365 days a year.

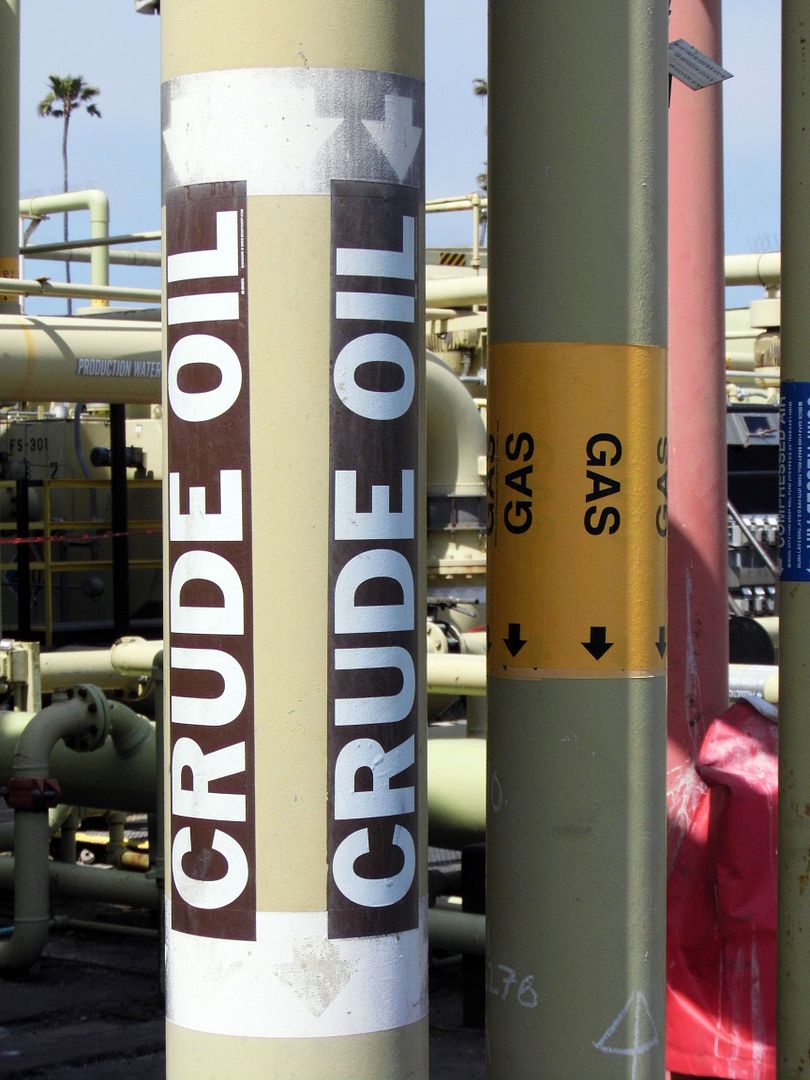

They mask some of the gritty operations from becoming visible to Long Beach residents and tourists alike, too. Although much of the activity happening on the islands isn't above the platforms, but underneath—as deep as 8000 feet! As many as 731 active wells—including horizontal ones—"fan out" under the islands from a single drilling site, minimizing the surface area needed.

If Long Beach was going to tap into the Wilmington Oil Field at all in the 1960s, it would have to build these islands with technology to prevent the city from sinking. When you extract crude oil, you also get water, silt, sand, etc.—and all that leaves an empty space. From 1930 to 1956, the land surface at the Port sank nearly 30 feet—a phenomenon known as "subsidence"—because there was nothing to replace the void that was left behind.

Now, they keep the islands (and the shore) from rising or falling by injecting (mostly recycled) water into aquifers, thereby stabilizing reservoir pressures and surface elevations. The whole thing is monitored by sensitive GPS, which tells them when to stop pulling oil and start pumping water, and vice versa.

So far, total oil production for the islands is about 1043 million barrels of oil (MMBO), or 1.043 billion barrels—which is a little more than a third of the Original Oil In Place (OOIP), estimated at 7 billion barrels. They hit the 1 billionth barrel mark in 2011.

Right now, they're getting about 20,000 barrels of crude oil a day. Ultimately, they'll probably get 3 billion barrels total.

Among the costs that are rising most steeply is actually electricity—for which you can at least partially blame those nighttime lighting schemes and manmade waterfalls.

But there's more to the THUMS island operations than just drilling oil, pumping water, and beautifying the whole process.

There's also pigging.

That's the term used for how they clean out and inspect the pipelines.

Apparently the first apparatus ever used in such a manner sounded like it was squealing like a pig.

And that's one sound the Long Beach neighbors definitely don't want to hear.

The THUMS islands have captured the imaginations of all those who've noticed them—either from the shore or by boat. Adding to the mystery is the fact that the "buildings" actually move along a track around the circumference of the islands, depending on where they need to drill.

Long Beach never exactly became the "Riviera of the West," but people still mistake the oil islands for offshore hotels or even casinos. Local businesses are quick to perpetuate the myth.

When the islands were built, it was estimated that they'd only be in operation for 35 years—and after 1990, they'd be turned into amusement parks.

I guess back then, nobody considered the decontamination that would need to happen before any of these islands could be used for pubic recreation. Many former oil fields are now superfund sites.

But the oil islands will eventually stop producing oil and will close.

I hope we get to keep them.

Related Posts:

The View By Boat

Photo Essay: Chevron's El Segundo Refinery

Photo Essay: Ventura Oil Refinery, Abandoned - Part 1

Nice article--glad you could join us! :)

ReplyDeleteWonderful photos and stories beneath each. I was hoping for a picture of old Signal Hill from the 30's. I remember it and how fascinating it was for a kid to see all those pumps working. I remember the smell too - my uncle loved it - he may have been the only one who did. Did you know that during the Christmas holidays they turned the pumps into a vision of Santa and his sleigh with reindeer bobbing up and down in front of the sleigh, looking as if they were pulling it. At night it was all lit up and quite an eye full for passing cars and people gawking. Love to have a picture of that, but we didn't think of that at the time. Thanks for the info and pictures.

ReplyDelete