The Greystone estate he built for his son Ned looms over streets named Doheny Road and Doheny Drive, in the hills directly above where I live.

I'd toured the mansion and traveled those roads enough to think I knew the oil baron's story.

But even having visited the Doheny Mansion on Chester Place in LA environs farther east, and the Doheny Memorial Library built in Ned's honor on the USC campus, I had more to learn.

And I had to cross the county line and go to the City of Brea to discover a major missing piece of the puzzle.

The word "brea" means "tar"—just like the La Brea Tar Pits and La Brea Avenue, both of which seep our natural source of "black gold" no matter how much we try to pave it over.

But within the Brea boundaries, there's another town—a forgotten one that's all but disappeared.

That is, all except the Olinda Oil Museum.

This marks the spot where oil put the town of Olinda on the map—by 1898, 10 wells had been drilled into the hillsides here. Olinda was a boomtown in the 1920s, at its peak housing 3000 workers and their families in 700 cottages and other dwellings—and boasting one of the richest school districts in Orange County.

By 1949, the Brea-Olinda oilfield ranked #18 in the country—but you'd never know by visiting the grounds of this former company town, now a ghost town, whose last residents moved out 1950s-60s with the construction of various local dams (including the nearby Carbon Canyon Dam).

It's now been transformed into a 12-acre historical park, the oil operation's former lease office/headquarters (built 1912, vacated 1999) now serving as a museum that collects artifacts and tells the story of how crude oil and water became big business—especially in powering the railroad.

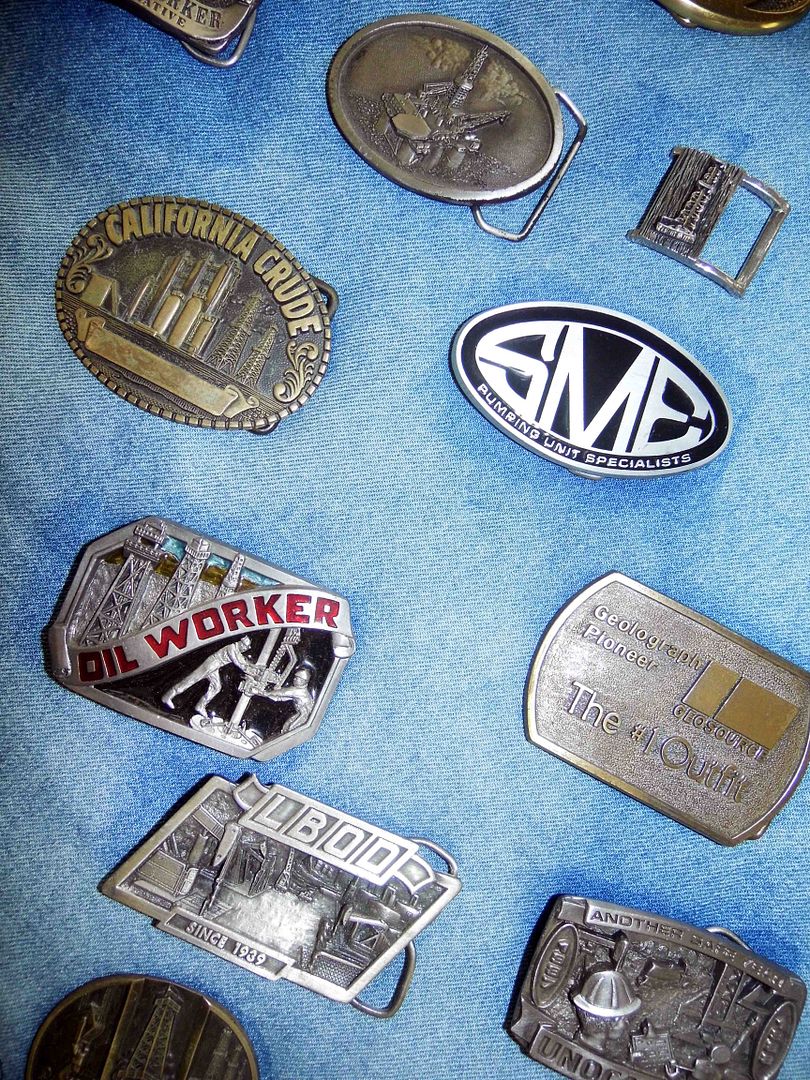

Through photographs and memorabilia, it provides a slice of life of oil workers and the "wildcatters" (or oil prospectors) that migrated to Southern California in droves—primarily from Pennsylvania, whose oil rush had already peaked by 1891.

Southern California's most infamous wildcatter, the elder Doheny, simply expanded his oil empire beyond where he first struck black gold in Los Angeles—establishing Olinda Oil Well #1 in 1897 at only 806 feet deep. It once produced 50 barrels/day (bpd).

Now, 123 years later, that horsehead pump is still going—making it the oldest operating well in SoCal. It still produces about 2 barrels/day (operated and managed by Breitburn Energy Partners), even though it's been primarily preserved for historical and not economic reasons.

That still-working first oil pump is one of the many outdoor displays at the Olinda Oil Museum, which also has a pumping unit for shallow wells (less than 1000 feet deep, most pre-1920, like #1)—this one in particular once used by Shell Oil Company.

There's also a Jack Line oil pump unit, housed in its original central jack plant that once could power up to eight wells, as far as a quarter of a mile away.

To pump from deeper wells (1000-8000 feet in depth), units like the wooden "walking beam" pump, with its 10-foot diameter band wheel, were used from the turn of the last century to the 1960s.

You can see one alongside other equipment—some manufactured locally in Torrance by Union Tool Company—like a steam-driven high pressure pump (which feeds water into boilers), a "hit-and-miss"

engine that operated big pumping units and distributed water to cool engines until the 1970s, and a blowout preventer that kept oil from "gushing" when tapping into deep pockets of it that had been trapped by earthquake faults (in this area, the Tonner Fault). It was Union Tool that pioneered much of the technical advances in rotary oil drilling.

To get around Olinda's steep hills, you needed a low-gear automobile like the a Ford Model T (this one circa 1924), which operated at your choice of two speeds and the horsepower equivalent to that of a modern lawn mower.

After all, the oil business isn't just about drilling—or even just pumping.

You also need a rig to pull rods and pipes out of the wells...

...and a tractor that's outfitted with all the latest cable-pulling equipment.

In the absence of a mule or horse team, a tractor would tow a portable steam boiler (circa 1910-20) around the oil field to power various equipment with, well, steam. But funny enough, the steam boiler itself was fueled by crude oil, natural gas, coal, or wood.

In addition to Union Tool, some of the equipment was manufactured at the Torrance plant of National Supply Company, at one time the world's largest maker of oil well equipment.

The plant closed in 1985, after a steady decline in both steel-based industries and oil drilling.

But oil hasn't completely disappeared from Southern California—and besides the still-active oil well #1, you can also witness several other horseheads actively pumping away along a 2-mile loop that climbs 275 feet through the Puente-Chino Hills.

How much oil is actually left in, say, Olinda Well #9? Probably not much. But Breitburn wouldn't keep it pumping if it didn't still turn a profit.

Same goes for Olinda Well #104, which is also accessible right alongside the trail.

The former Olinda Ranch—once owned by the Olinda Land Company, located on what was once known as the Mexican land grant, Rancho Rincón de la Brea—became the first successful oil field in Orange County.

The old company town is gone—its schoolhouse relocated to become a senior center, its church and dancehall leveled, its Santa Fe rail spur decommissioned. Now, "Olinda Ranch" is a residential subdivision of Brea, adjacent to the still-operating oil field, and on top of the site of a former Santa Fe Energy Resources oilfield.

Wildfires rage through these hills (the last major one occurring in 2008). Seismic activity created these hills—and trapped this tar. So, why would anyone move here?

Well, maybe they're hoping for a "gusher" of their own.

Related Posts:

There's (Black) Gold Up In Them Thar Hills

Photo Essay: California's First Commercial Oil Well & Abandoned Company Town (Updated for 2018)

To Save or Open West Coyote Hills Oil Field, Abandoned

Photo Essay: Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area, Oil Adjacent

No comments:

Post a Comment