Adapted from my article for KCET's Artbound,

which you can read in full here.

Located in the City of San Marino (formerly the "San Marino Ranch"), most Angelenos know it as simply as “The Huntington."

I'd been there a few times before, and I'd even written about it—but I'd focused primarily on its plants (not the least of which is the corpse flower), even though the highlights of this historic property are at once horticultural, artistic, and literary.

And since it started celebrating its centennial in September 2019, it seemed like a good time to revisit The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens and see what I'd missed on my prior visits.

The Huntingtons were avid art collectors—and their 55,000-square-foot Beaux-Arts-style villa, where they lived luxuriously in the Gilded Age, first opened as a British art gallery in 1928 (a year after Mr. Huntington’s death) and now houses the European art gallery.

Primarily designed in 1909 by Myron Hunt (of the Ambassador Hotel and Rose Bowl), the exterior evokes at once a late 19th-century Italian or Spanish Renaissance country house and a French palace.

It’s perhaps most renowned as the home of “Pinkie” by Thomas Lawrence (acquired 1927) and “The Blue Boy” by Thomas Gainsborough (acquired 1921, currently off display during conservation efforts). I preferred gazing at the David Healey Memorial Window (circa 1898) from the Unitarian Chapel, Heywood, Lancashire (now demolished).

It's a two-story tall, 18-foot high series of leaded art glass panels that depict Truth, Faith, Love, Courage, Generosity, Charity, Justice, Mercy and Humility.

Designed in a mosaic style by Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, it was fabricated by William Morris's renowned firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Co.

The Huntingtons—in particular, Henry—were also big readers. And although there was a library within the Huntington mansion, the exponentially growing book collection soon outgrew it, necessitating the construction of a separate library building.

Now, one of the world's most renowned independent research facilities of its kind, The Huntington Library has collected more than 11 million manuscripts and other items dating back to the 11th century—from Shakespeare to Thoreau and even Benjamin Franklin and Jack London.

And over time, entire holdings—from such libraries as the William Bixby Library, Bridgewater House Library, Elihu Dwight Church Library and the Ninth Duke of Devonshire’s collection—have been acquired and added.

An entire wing of the library building is occupied by the Dibner Hall of the History of Science.

First opened in 2008 — and largely based on the Burndy Library collection of historian Bern Dibner — the hall covers astronomy, medicine, electricity, light, engineering, Darwinian evolution and other scientific disciplines of the Western Hemisphere.

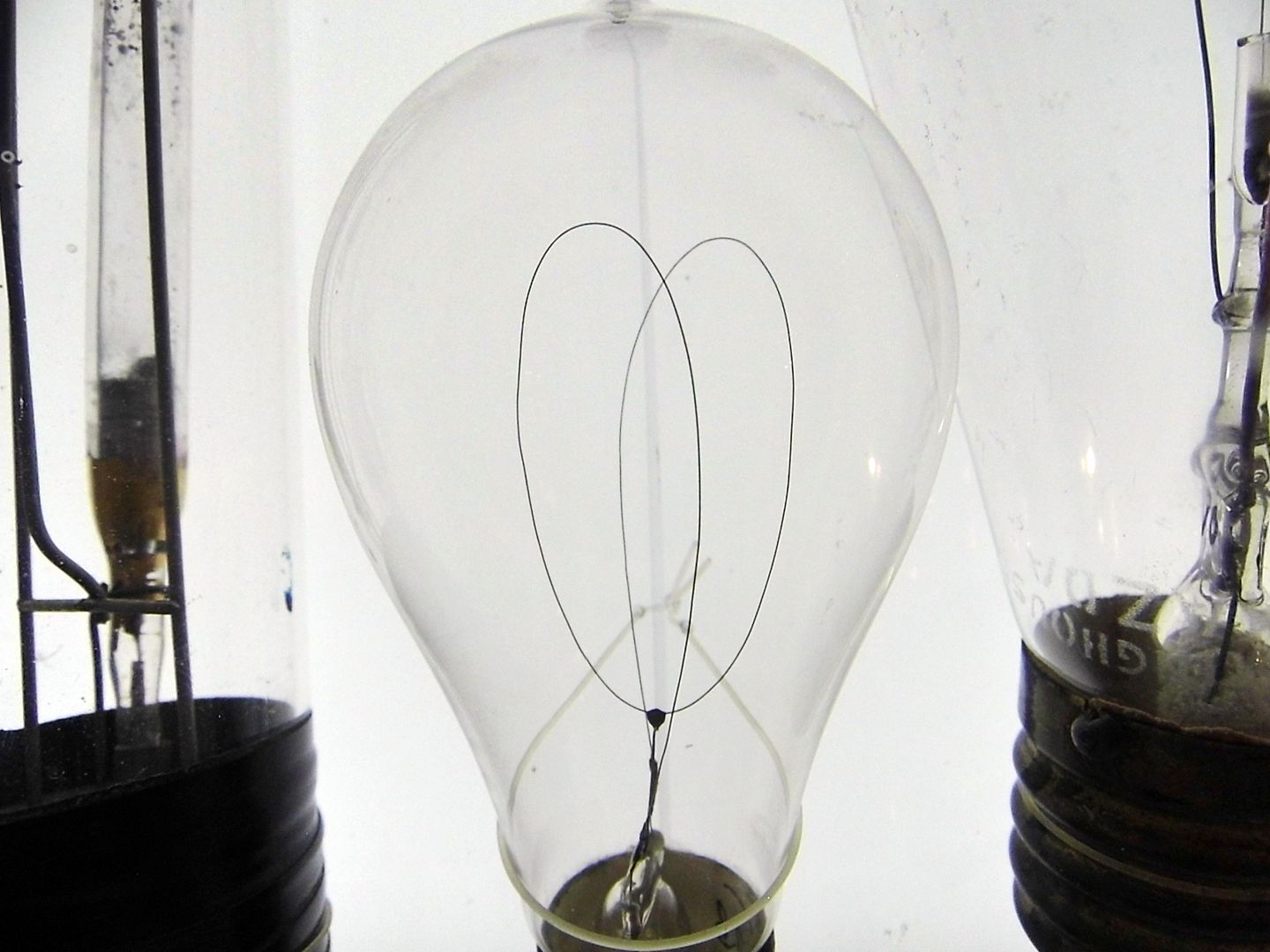

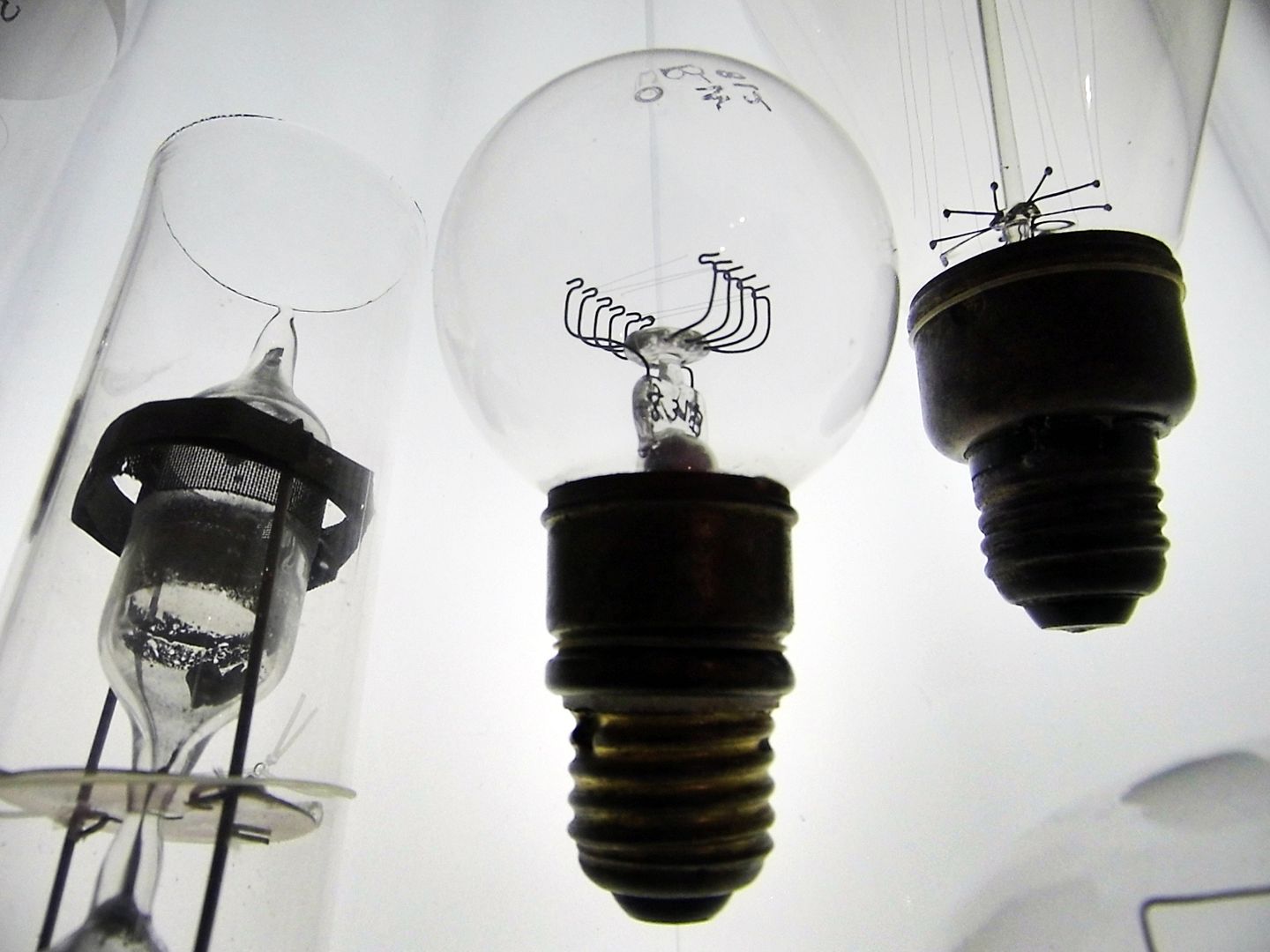

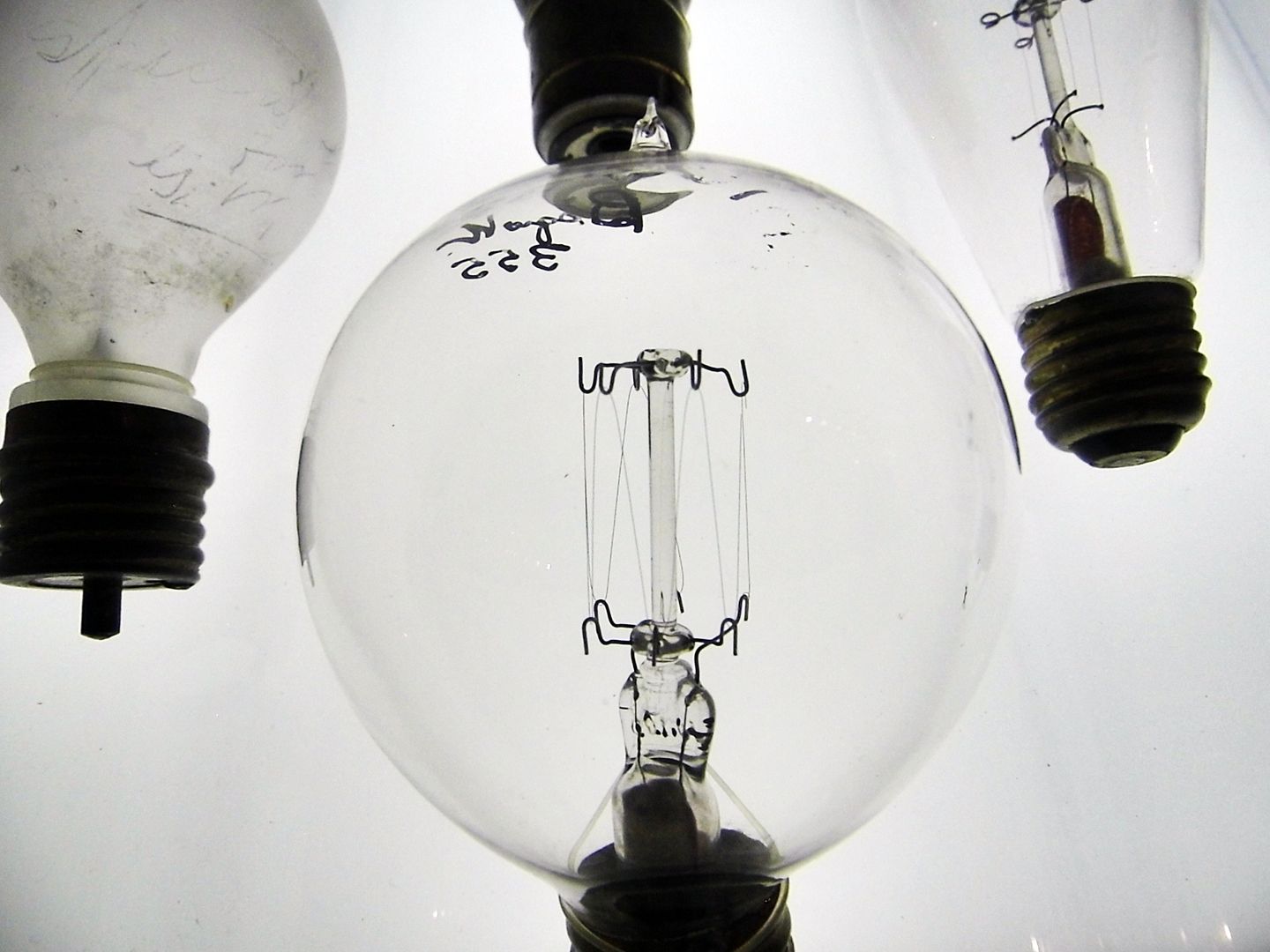

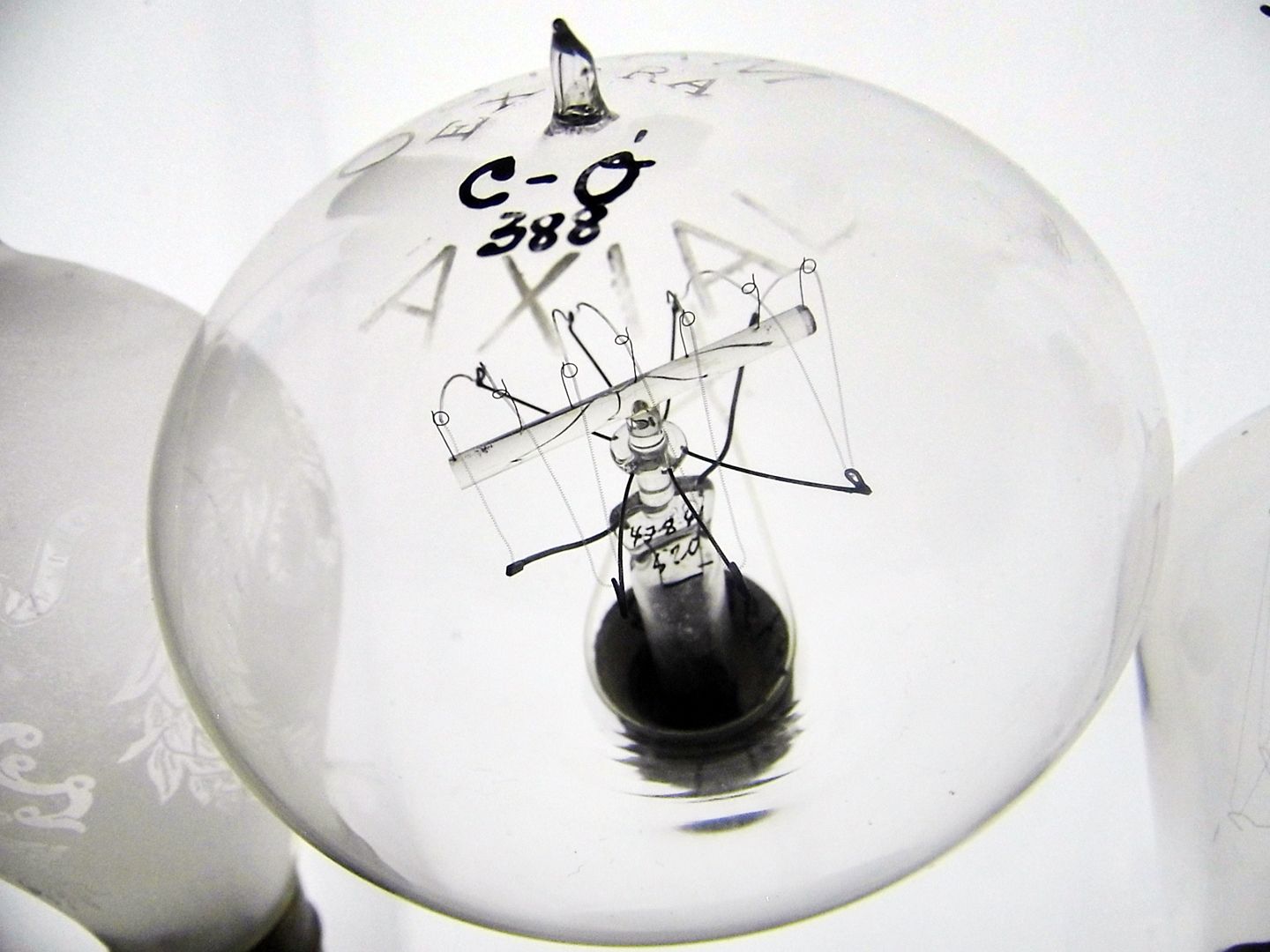

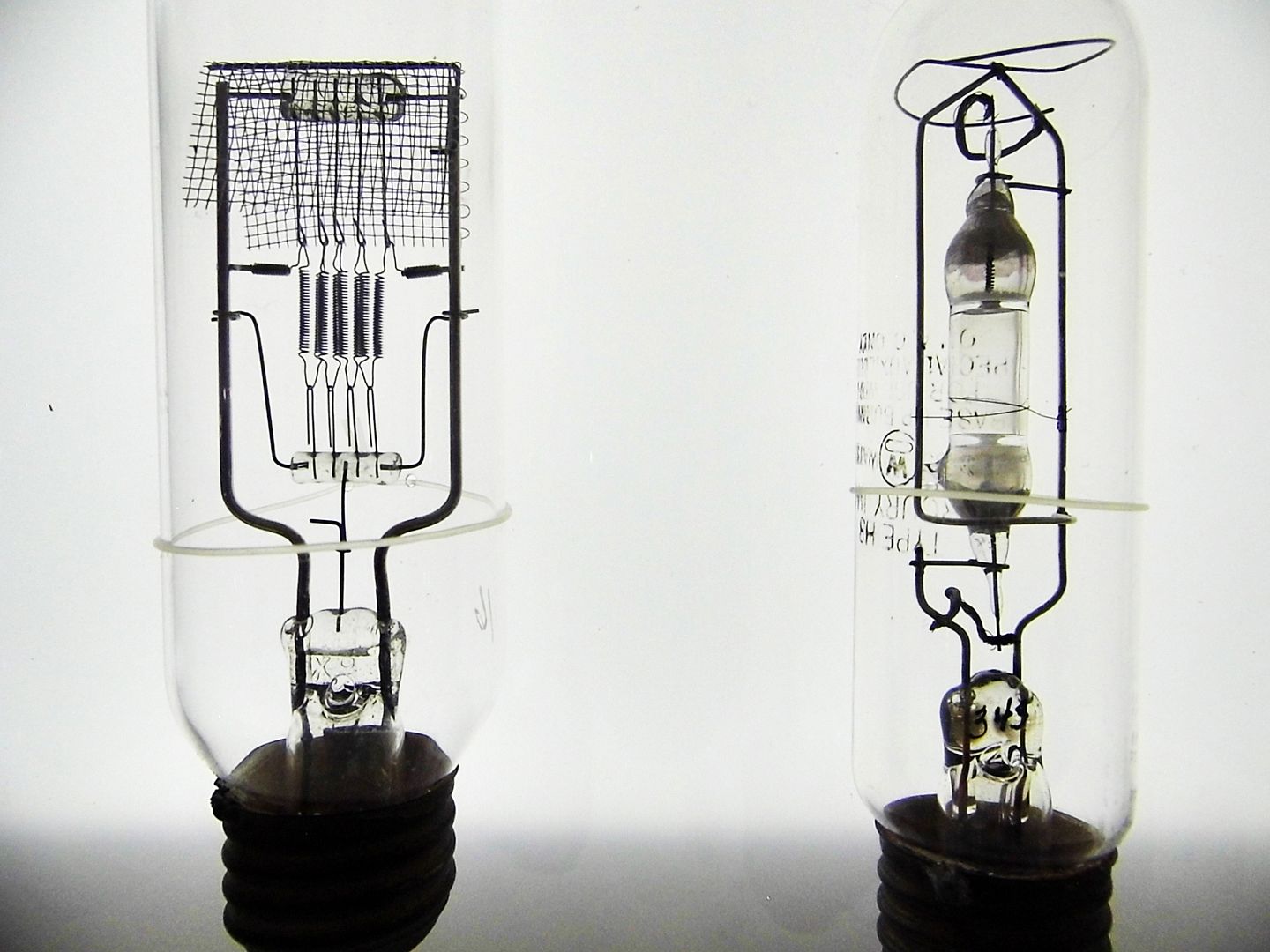

One of its most unique collections is of nearly 400 light bulbs, some hand-blown...

...originally amassed by Dr. Samuel Hibben of the Westinghouse Electric Company in the 1920s.

About half of them are on display, ranging from the 1890s to the 1960s.

Other intriguing objects include antique telescopes...

...anatomical models...

...early X-ray images, sundials, a camera obscura...

...an interactive display of Kircher’s mirror trick...

...and a replica of a microscope pioneered by 17th-century optician and microscope maker John Marshall.

These collections help make The Huntington one of the world’s most important destinations for students of the history of science.

I'd previously spent plenty of time in The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science...

...but this time, outside its entrance that faces the Children’s Garden, I discovered something new...

...the Hummingbird Gazebo...

....which attracts a flurry of activity from Anna's hummingbirds, Allen’s hummingbirds, and more.

My final stop on my centennial visit was a spot that Mr. Huntington himself loved so much, he was buried there.

Overlooking the gardens from a knoll above the orange groves, both Henry and Arabella Huntington are interred in a Greek-style temple, with a circular peristyle and dome constructed of limestone marble from Colorado’s Yule Creek Valley.

Completed in 1929, the mausoleum was designed by architect John Russell Pope, who went on to employ a similar approach to the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C.

In the inner colonnade, mounted onto the masonry of freestanding pillars, are marble bas-relief panels (painstakingly cleaned in a 2012 restoration) by sculptor John Gregory, representing how each of the four seasons relates to the four stages of life.

By creating this publicly accessible cultural resource, the Huntingtons ensured that their legacy would live on—not only in terms of their land and their holdings, but in the continuing pursuit of the world's plants, paintings, and printed matter.

To read more at KCET.org, click here.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: The Blooming, Stinking Corpse Flower (and Other Delights) at Huntington Gardens

Photo Essay: Deadly Fruit, Meat-Eating Plants, and Other Oddities In Bloom

No comments:

Post a Comment