But a closer look reveals that it's a complex of three buildings, each with its own owner who leased the land they were built on—a total of seven separate parcels.

And it may soon lose one of those three historic structures. Because it turns out that they're not as seamlessly linked as you might think.

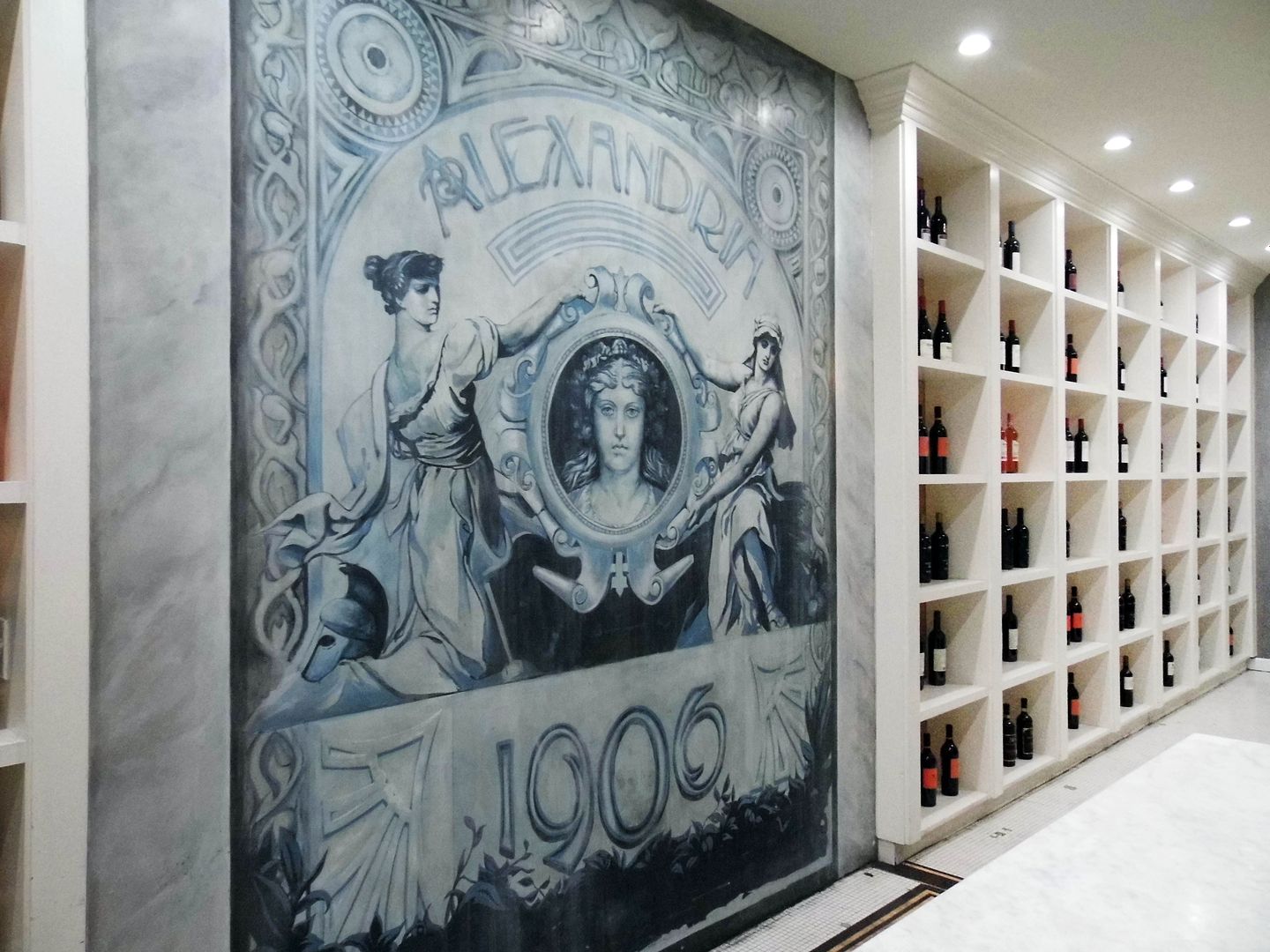

Named after owner Harry Alexander, the first (or "main") section of the hotel was constructed by the Bilicke-Rowan Fireproof Building Company—developers Albert Clay(A.C.) Bilicke, president of the Alexandria Hotel Company, and Robert Arnold (R.A.) Rowan—in 1906 for $2 million, an almost unheard-of cost at the time.

Architect John Parkinson (Bullocks Wilshire, Union Station, City Hall) created the 8-story, Beaux Arts hotel with 360 rooms—each with private bathrooms, central heating, and automatic do not disturb signs on the doors.

Although the pressed brick façade (by Pacific Clay Manufacturing Company) with terracotta balustrade may look relatively simple, The Alexandria Hotel was the most elaborate in LA at the time, offering luxury and drawing upscale clientele. Some decorative sculptures placed on top of the decorative parapet with balusters divided by columns were removed in the 1950s.

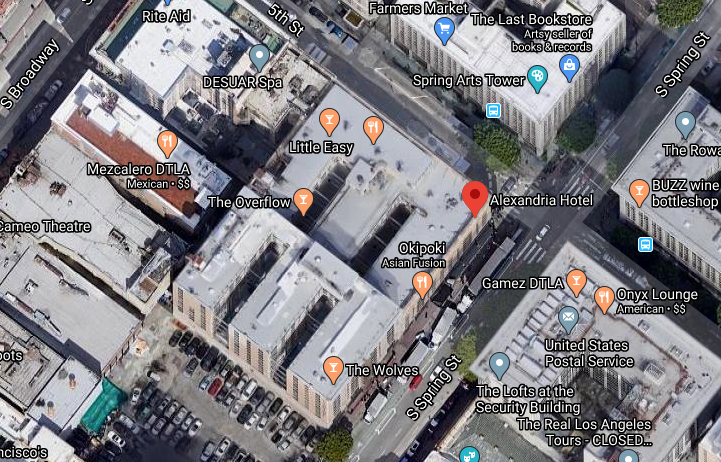

But the cast stone chimeras still provide a unique character to this corner lot at 5th and Spring in the Historic Core of Downtown Los Angeles.

Screenshot: Google Street View

Screenshot: Google Street View

In 1911, a 12-story addition—technically, the "Second Addition," or "the Spring Street Addition"—was constructed out of reinforced concrete immediately to the south of the original steel frame "main" structure, also designed by Parkinson with his partner G. (George) Edwin Bergstrom.

This third and final addition helped bring the hotel's capacity up to about 500 rooms and kicked off a heyday that would last until about 1922, after which its popularity was eclipsed by the newly opened Biltmore Hotel a few blocks away.

But what a heyday it had, for those 11 years.

At the time, 5th and Spring was considered to be the "up-and-coming" shopping area, as the center of Los Angeles was moving west and south from its pueblo beginnings. Its proximity to Broadway's bustling nightlife didn't hurt, either.

The Alexandria Hotel became a hangout for Hollywood execs and silent film stars like Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and Rudolph Valentino—so much so that the Persian rug in the lobby got nicknamed "million-dollar carpet" because of all the deals being made there.

The Spring Street addition's ground floor included a 196-foot long banquet hall called the Franco-Italian Dining Room, later known as the Grand Ballroom and the Continental Room, and now called the Palm Court. Of all the interior spaces in the hotel, it's the most intact.

Upon its opening, it was already the city's most prestigious ballroom—but speeches given by U.S. Presidents William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson and a wedding ceremony between Gloria Swanson and Herbert Somborn in 1919 cemented its reputation. (The couple also honeymooned at the hotel and even lived there for a few years after.)

The Palm Court's most distinguishing feature now is its stained glass skylight, widely attributed to Louis Comfort Tiffany. It was painted black during World War II (so as to not aid enemy aircraft) and forgotten about—but later rediscovered and restored. It's what helped earn the Palm Court its designation as a City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM#80) in 1971—one of the few “interior-only” HCMs in the city.

Unfortunately, the original Italian and Egyptian marble has been removed from the hotel lobby—which, after several redecorations and a later gutting, has been rendered unrecognizable. But they kept a little bit of the marble on the walls at the stairs leading to the basement.

Across from a frieze of cherubs, you can climb the marble-floored staircase up to the mezzanine...

...holding onto its iron railing by an oak handrail...

...and emerging into a loft-like space called "The Mezz," now used as a venue for weddings and such as part of the Alexandria Ballrooms event planning service.

Upstairs you'll also find the former Rose Ballroom, its French windows opening out onto the Spring Street side of the building, with its original beamed ceiling and hardwood floors.

It's now called the "King Edward Ballroom"—incorrectly so, since apparently the rumor that King Edward ever visited the hotel has been debunked. Harry Houdini and his wife Bess, however, did celebrate their 25th wedding anniversary in that room.

Colloquially, some people still call the former Rose Ballroom the "Paula Abdul Room," because of the music video she shot there for the song "Cold-Hearted" in 1989, directed by David Fincher.

The video (above) gives a great glimpse into how the room looked 30 years ago—which is remarkably pretty much the same as now, except for the paint job on the walls.

Like any other successful hotel, The Alexandria boasted both private ballrooms and eateries for their guests and visitors—including the Peacock Inn Coffee Shop (now a private bar available to rent) and Gentlemen's Grill upstairs (which sometimes women weaseled their way into).

Down on the lower level, underneath the Spring Street Addition, was the Mission Indian Grill (a.k.a. Indian Grill Cafeteria). It was converted into an underground parking garage, the tile floor paved with asphalt. But foot and tire traffic have been wearing that blacktop coating away, revealing little bits of the original tile, piece by piece.

Despite its massive success, the Alexandria Hotel ultimately couldn't overcome the local competition (like from the Biltmore) combined with the Great Depression. It went bankrupt and closed in 1932.

It did reopen a few years later and experience somewhat of a revival—but as it changed hands time and again over the following decades, it was slowly stripped of its grandeur.

In the mid-1950s, boxing matches brought rowdy crowds. In the 1970s, the banks left the Spring Street financial district.

What once was a destination for fine dining now brought customers in with concepts like the Guv'Nor's Grille—a kind of British pub/surf n turf establishment on the corner of 5th and Spring at street level in the late 1960s/early 1970s. (It's now occupied by The Down And Out Bar, though a shield-shaped bronze bas relief still promotes steaks, chops, and seafood on the corner column. Prior to that, it was Charley O's Cocktail Bar, which seems to have closed in 2010.)

In the 1980s, the Alexandria Hotel had become overrun with drug dealers taking advantage of its weekly rates. By 1988, it was called "the worst drug-trafficking spot in Los Angeles" by city officials.

Rezoning it later as a low-income housing property/single room occupancy (SRO) didn't help the blight much. Neither did its proximity to Skid Row (5th Street a.k.a. "The Nickel").

It's now a mix of market rate and subsidized housing—and still a popular filming location.

None of those challenges have kept developers from trying to revitalize the Alexandria, much like other vintage buildings in Downtown Los Angeles have been given new life.

But for the Alexandria, that may come at the sacrifice of one of its three sections—the ghost wing.

That wasn't always the plan. In 2012, the sealed-off second building was sold and slated to be developed into the 35-room "Chelsea Building."

But since that time, the deterioration has been deemed "irreversible"—and developers argue that they'll need to entirely rebuild the interior to include some stairways and an elevator.

They will, however, preserve the façade—which, as one letter of support put it, is an "irreplaceable contributor to the historic fabric and artistic architectural aura of Downtown LA"—in a practice that's been nicknamed a "façadectomy."

The result will be The Annex, with 31 residential units. Applications for the project to move forward were filed as recently as 2018. But no work has begun.

In the meantime, you can enjoy other public areas of The Alexandria (besides The Down And Out) by patronizing The Wolves on the ground level of the Spring Street Addition and The Little Easy, a subterranean spot below the main hotel.

People say the whole thing is haunted—and you can bet it's not by Rudolph Valentino (because if that were true, man does he ghost get around).

The Alexandria's most famous ghost is "the woman in black," who walks the halls for all eternity.

But it's possible that there's lots of other bad juju that hasn't been cleared out of the hotel—including some recent events, like when an 87-year-old man fell to his death in 2009 or another man died jumping from the 4th floor in 2013.

I don't plan to stick around long enough in that building to find out.

Related Posts:

Riding the Red Line to Haunted Hollywood

I remember my crew and others, threw a News years event there in 1987.

ReplyDelete