And although I'd thoroughly visited the Fort MacArthur Museum (located in the fort's Upper Reservation) a few times over the last few years, people kept telling me they thought there was more to see.

Turns out they were right—because in 2018, I returned to the Battery Osgood-Farley and got into some rooms I never knew existed.

Of course, it's all been declassified now—but these are areas that aren't usually open to the public, like the Battery Commander's Station. That's where the B.C. could observe the firing of the guns from a observation station that afforded him a clear view of the field of fire (accurate to 1/100th of a degree).

It's also where they could track targets and report their positions to the plotting room, located directly below them, so they can triangulate the targets and point the guns properly and accurately (in terms of both distance and direction, or azimuth, as measured from the artillery).

From there, they had complete control over the battery's operation—thanks to a series of seven "speaking tubes."

This U.S. Army post guarded the LA harbor from 1914 to 1974.

And sometimes, the most basic technology turned out to be best.

I also knew that there were some tunnels that ran from the Ft. MacArthur Museum to elsewhere in San Pedro—but whenever I asked anyone in charge about them, they'd say things like, "Oh, there's nothing down there to see" or "It's just used for storage now."

That wasn't, in fact, true—which I would find out later in my explorations beyond the public eye.

But first, I had to hit the Communication Room. Fortunately, it's no longer "gas-proof"—so a hard blast of air didn't have to "blow off" any poison gas in the decontamination room before I entered.

This was "ground zero" for the United States Army Signal Corps (USASC)—critical for detecting an approaching enemy they couldn't see (not even with a telescope). That meant aircraft.

This is where communication specialists and, essentially, information technology personnel would use radio receivers and transmitters—not only tuning but also calibrating and encoding across multiple frequencies.

In terms of detecting an incoming threat, obviously this is where RADAR (Radio Detection And Ranging) would really come in handy.

But switchboards—for both telephone and telegraph—were also critical to the missions.

And sometimes communications boiled down to a more analog form of communication—namely, typewriters.

Oh, and don't forget about Teletype (TTY)—the great-granddaddy of email.

And of course there was also Morse code...

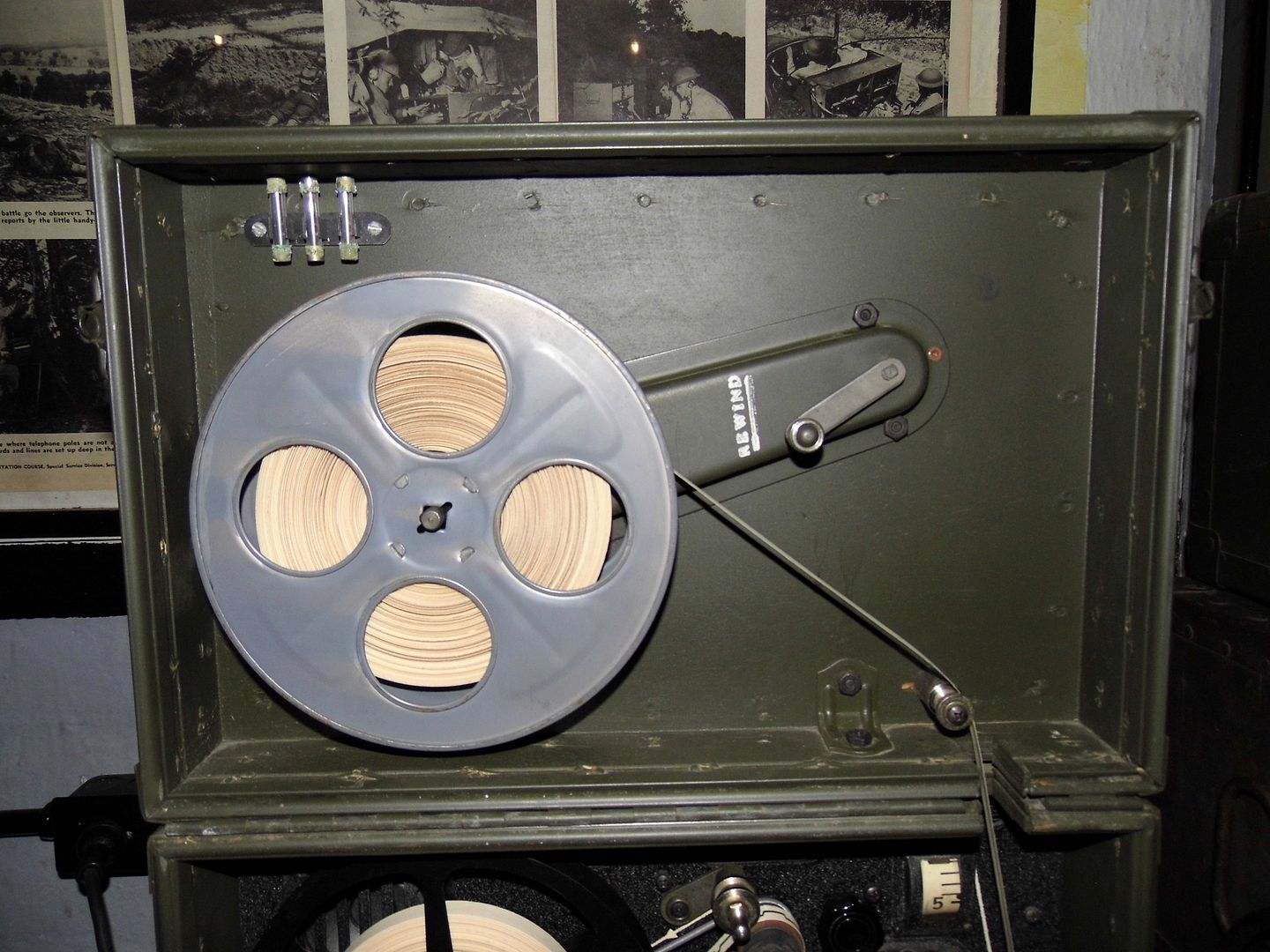

...which radio operators (or "keyers") would learn on a special Signal Corps "learning machine"...

...as paper "practice tape" spat out signals recorded in ink for playback.

But what better communication was there for those enlisted in the U.S. Army than good ol' paper mail? Handwritten letters on perfumed paper in lipstick-sealed envelopes beat electronic communiqués any day.

This was the first time in recent memory that the Fort MacArthur Museum had opened up these areas (formally, anyway) to the public. And it hasn't again in the last two years, as far as I can tell.

Stay tuned for more dispatches from other "underground" areas around the various reservations of the former Fort MacArthur.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: Fort MacArthur and The Battle of Los Angeles

Photo Essay: Trespassing Through Southland's Military History

No comments:

Post a Comment