[Last updated 2/8/25 9:43 PM PT—Added Mel's section to the bottom of this post.]

♫"...If you think that you can be an actor, see Mr. Factor,

he'd make a monkey look good..."♫

- "Hooray for Hollywood"

Growing up in the age of drug- and department-store cosmetics like Revlon, Cover Girl, and Maybelline, it's easy to think that "Max Factor" was just another brand name.

In fact, some people have theorized that Max Factor is a kind of portmanteau of the medical practice of "maxillofacial" surgery, or "Max Facs."

But there was, indeed, a Max Factor—or, rather, a Maks Faktor.

Born in Poland, Maksymilian Faktorowicz is the man we should credit for inventing lip gloss—and many other staples of our everyday makeup cases.

He's the one who created the heart-shaped lips—like those of a Pierrot clown—for silent movie star and "It Girl" Clara Bow.

His pedigree was unmatched, having worked for the Imperial Russian Grand Opera's cosmetician at only age 14. Later, he became the on-call beautician to the family of Russia’s Czar Nicholas II.

After immigrating to the United States, and moving to LA with his family in 1908, he founded Max Factor & Company in 1909. Without a permanent headquarters, he set up shop in various different neighborhoods and in buildings that weren't his own (including, for a while, the Pantages building).

In 1913, he caught a break when he persuaded Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille to rent the wigs he'd custom-made.

But in the land of make-believe, it was "make-up" that brought Max Factor the most attention.

Until he started "making up" both starlets and average women, the term "make-up" was only associated with theater actors and vulgar women with bad reputations.

That all changed after he settled into his own home—and threw the doors open to the public, welcoming them into an opulent setting that was perfect for lured high-society and professional women (and way too nice for hussies).

circa 1939 (Photo: Works Progress Administration Collection, via LAPL)

He chose the Hollywood Fire and Safe Building, built in 1913, as his future home in 1928—disastrously close to the stock market crash that would delay its opening until 1935.

circa 2020

That gave the architect he hired, S. Charles Lee, plenty of time during the Great Depression to turn the cosmetics king's headquarters into the "Jewel Box of the Cosmetic World." Known for his movie palace designs, Lee operated under the premise that "The show starts on the sidewalk."

all photos circa 2019 except where otherwise noted

Factor died just three years after its opening, at only 61 years old. His son Frank legally changed his name to "Max Factor, Jr." and took over the business, with the family controlling it until its sale into Corporate America in 1973.

The company changed hands several times—with attempts to move the Max Factor headquarters back and forth between LA and New York more times than anyone could count. By the 1980s, the grand salon of the make-up studio was no longer hosting Hollywood's up-and-coming stars—so it was converted into the Max Factor Museum of Beauty as a tourist attraction during the 1984 Olympics.

Procter and Gamble took over the company in 1991 and decided to shut the museum down—alarming local activists, who launched the "Save the Max" campaign to preserve the building. In 1994, Procter and Gamble sold it to real estate speculator and Hollywood memorabilia collector Donelle Dadigan [above], who founded The Hollywood Museum and still holds the title of its President today.

Restoring the Max Factor Building to its original grandeur took nine year—and as a result, The Hollywood Museum has been open since 2003, with much of the historic lobby dedicated to the legacy of Max Factor.

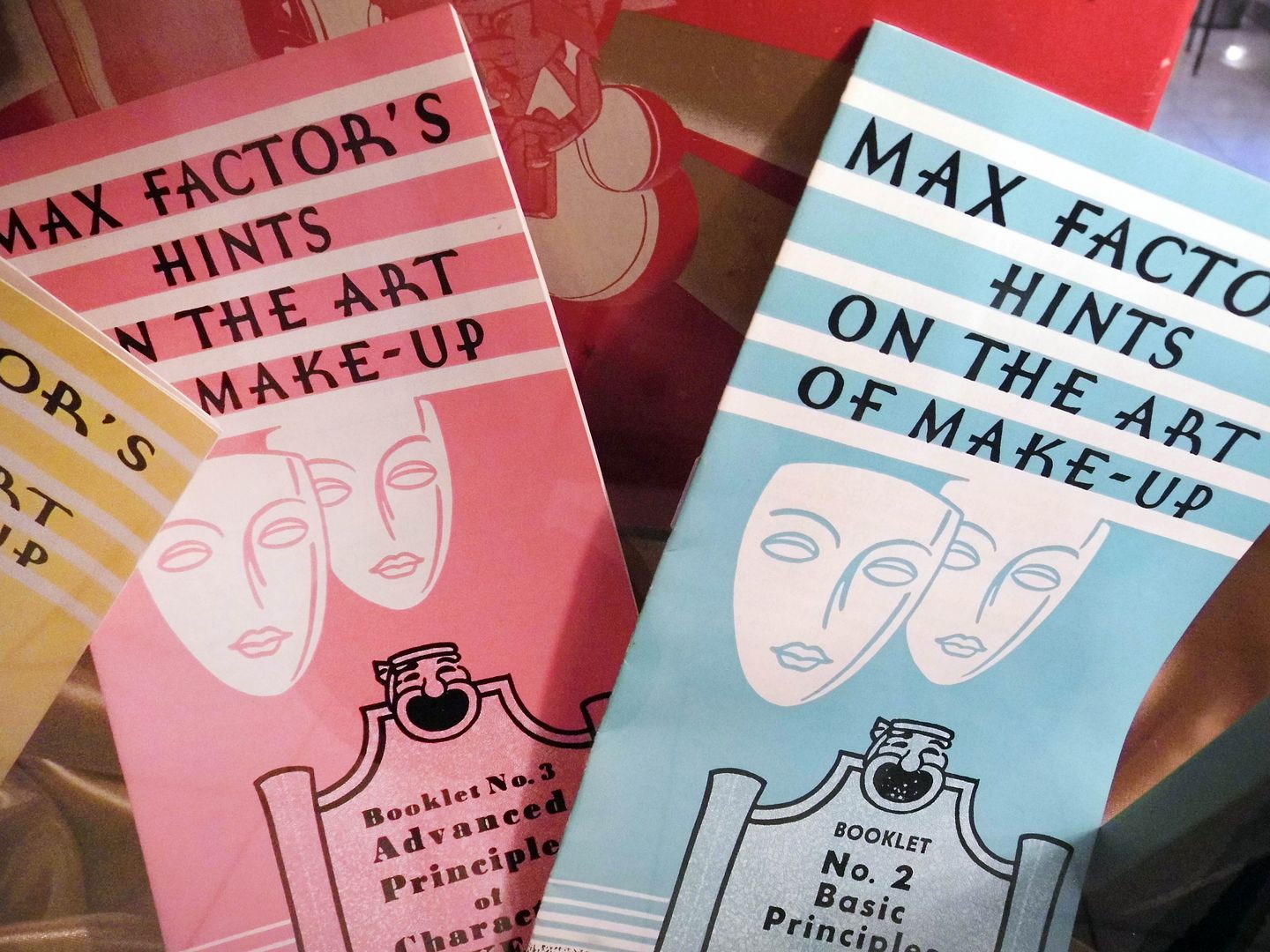

The story its displays helps tell is that Max Factor wasn't the one to do certain cosmetics first—but also better than anybody else, starting with greasepaint. His "flexible" version was thinner and could be applied more evenly for the camera than the "stick" version for theater that would crack and go on too thick. Max Factor's cream greasepaint also came in 12 different subtle shades.

His biggest order to fulfill was for 600 gallons of light olive makeup to be used on the cast of Ben-Hur—particularly the extras, whose facial tones needed to match each other (especially those players who shot in two different locales).

Cosmetic and fragrance research labs were located just behind the salon on the first floor of the Max Factor Company. Later innovations to come out of the company included the smear-proof Tru-Color Lipstick in 1943—whose resistance to fading was tested by a kissing machine.

The cosmetic empire also included sweat-proof body make-up and, in 1971, the first "waterproof" make-up.

Offices, the hair department, and consumer products manufacturing and packaging facilities occupied the upper three floors of the building—now devoted to rotating exhibits of movie and television memorabilia and costumes.

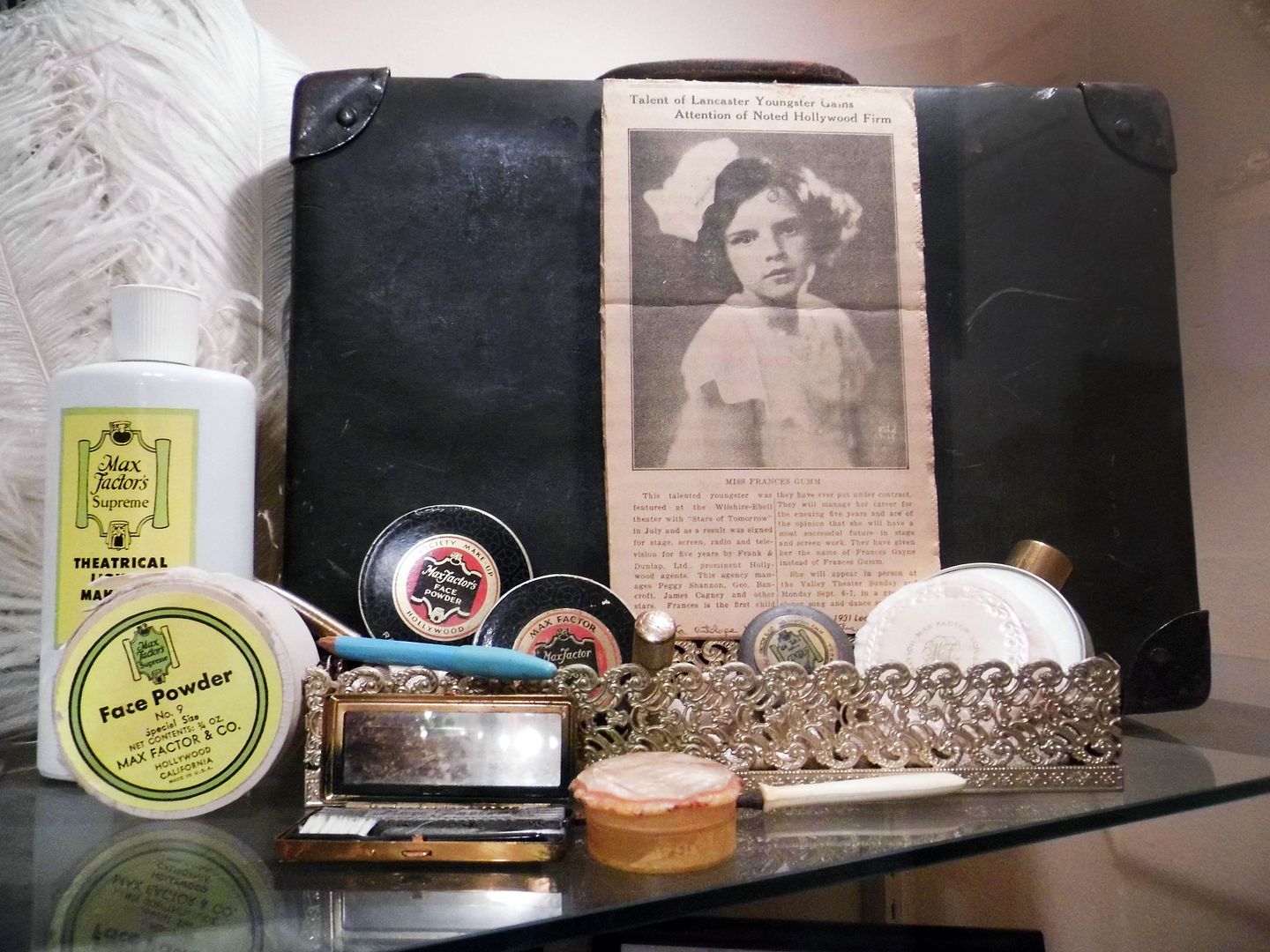

But the first floor still has plenty of star power—because in addition to Max Factor's personal make-up case that's on display, there's also Greta Garbo's personal make-up case, its contents bursting with Max Factor cosmetics.

Judy Garland's personal make-up is part of the exhibit, too.

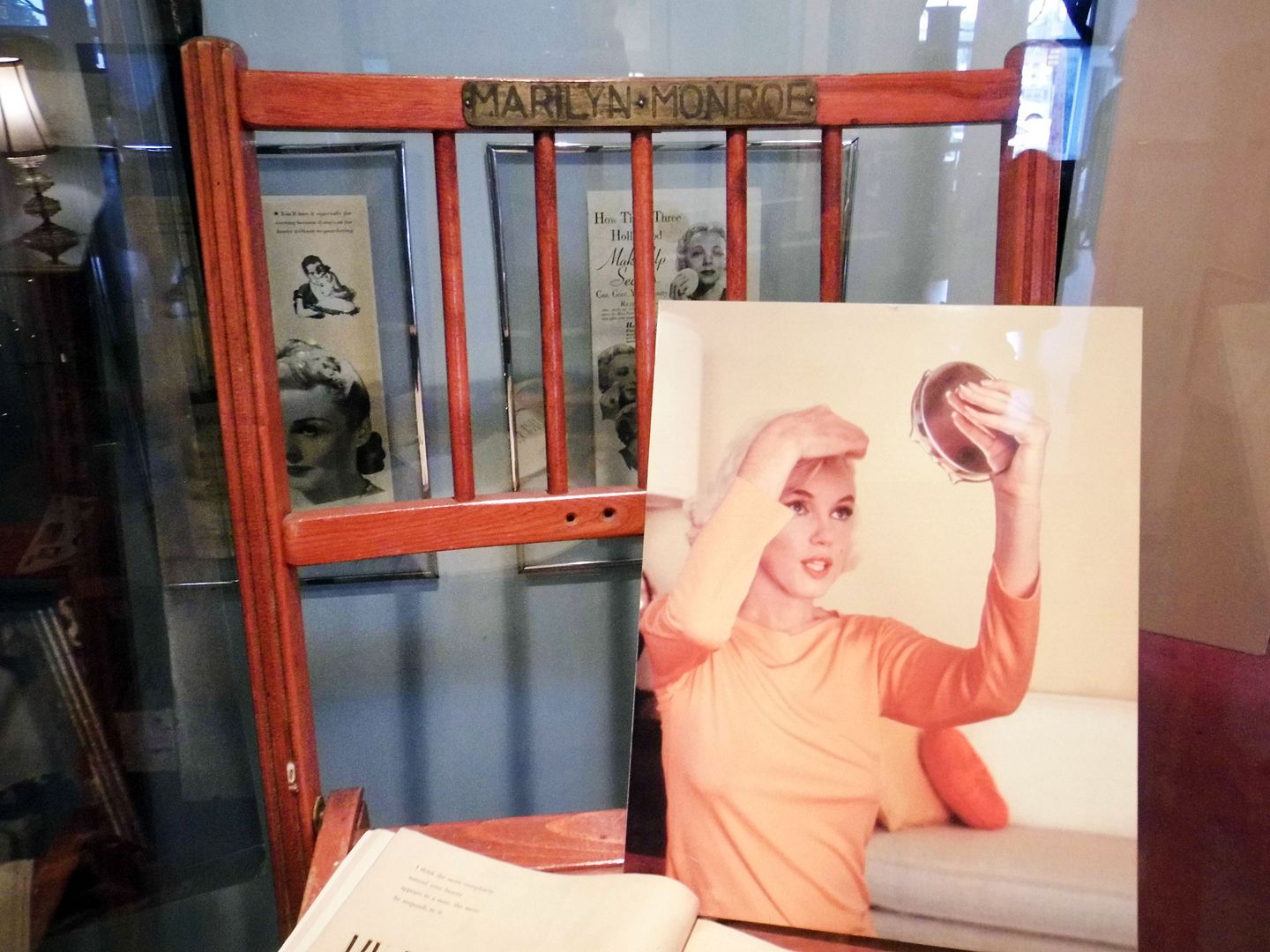

And you can step into the room where Factor created the "blonde bombshell" look—a "platinum" blonde that he debuted on Jean Harlow and recreated for Marilyn Monroe, both former "brownettes." (The current museum also boasts the largest Marilyn memorabilia collection in the world.)

Factor began developing his "Color Harmony" technique in 1918—which theorized that the right color room could determine the perfect palette for the camera—but he perfected it not only with blondes, but also natural brunettes (like Elizabeth Taylor, Joan Crawford) and "brownettes" (like Bette Davis) and converted redheads (like Lucille Ball, a blonde, and Rita Hayworth, a brunette).

Max Factor's most attention-getting invention, however, was the Beauty Calibration Machine a.k.a. Beauty Micrometer circa 1932—also on display in one of the historic make-up rooms. It attempted to dispel the myth of the natural, "perfect" face by detecting imperceptible unconformities in the entire craniomaxillofacial complex.

If your face was going to be filmed super close-up and projected super-huge on a screen—especially in the advent of color film—corrections would need to be made to your nose, cheeks, mouth, jaws, and who knows where else.

And Factor had just the make-up for that—his Pan-Cake make-up for Panchromatic and, later, Technicolor film. It was the predecessor to modern-day face powder, compressed into cake (or "pancake") form.

Update 2025: After you visit the museum, there's one more stop to make—the Hollywood outpost of Mel's Drive-In.

It's occupied the attached makeup studio and wig shop annex (circa 1935, nicknamed "The Pink Powder Puff") since 2001.

It's not like the other Mel's Drive-In restaurants in the Los Angeles area—the Googie-style former Ben Frank's on the Sunset Strip, or the Armet and Davis-designed former Penguin's in Santa Monica or former Kerry's Coffee Shop in Sherman Oaks.

It feels like of warehouse-y and industrial if you look up at the ceiling—but with that horseshoe-shaped counter and those curved booths, it's unmistakably Mel's.

No comments:

Post a Comment