Fifty years is the bar that's been set for so-called "historic significance"—and if a building is younger than 50 years old, it's darn near impossible to get it landmarked.

But the San Diego Civic Theatre has hit 55 years, having opened on the night of January 12, 1965 with a performance by the San Diego Symphony. Since then, such luminaries as Frank Sinatra, Johnny Cash, Bob Hope, Jerry Seinfeld, Diana Ross, and Maya Angelou have graced its stage—while organizations such as Broadway San Diego, California Ballet, San Diego Opera, and La Jolla Music Society also call it home.

Maybe the four-story, semi-circular performing arts center—with more than a few Brutalist tendencies—is easy to dismiss, compared to the movie palaces that were built decades before. But the Civic Theatre is important—if only for its role in helping to catalyze the development of Downtown San Diego with the creation of the San Diego Concourse complex (a.k.a. Charles C. Dail Concourse, in honor of former Mayor Charles C. Dail, who served from 1955 to 1963).

The Concourse development also included a new City Hall, a convention center, and a parking garage—and the Civic Theatre was the last of the cluster of buildings to open and provide a a stage for civic gatherings.

The Civic Theatre does benefit from its association with the Bow Wave Fountain by Malcolm Leland— added to the Concourse in 1972 in conjunction with the Security Pacific Bank tower (which is technically outside the concourse boundaries). Constructed with a steel frame clad in layered sheets of copper, the sculpture evokes the bow of a ship cutting through the sea (even when the fountain's water feature isn't spraying properly).

Like the fountain, the Civic Theatre is owned by the City of San Diego—which has leased it to San Diego Theatres, a non-profit organization that manages it along with the Balboa Theatre (photo essay coming soon), through the year 2063.

But part of the leasing terms is that $30 million worth of renovations have to break ground by the year 2023—and that's not going to come from ticket sales, especially when the rest of the 2020 season has been canceled, postponed, or otherwise rescheduled in light of the coronavirus pandemic. In 1966, the Civic Theatre raised $36,000+ to install a Bavarian crystal chandelier in the Grand Salon through contributions from community donors. What could they raise today?

It's unclear what those renovations might be—and whether they'll take place on the exterior plaza or will address the interior, which, like the exterior, was designed by the architectural trifecta of Ruocco, Kennedy and Rosser.

Lloyd Ruocco FAIA, widely considered the "Father of San Diego's Post-War Modern Architecture" (the "war," in this case, being WWII), collaborated with Selden B. Kennedy, Jr. and William Frederick Rosser to create the city-owned performing arts theatre at a cost of $4.1 million.

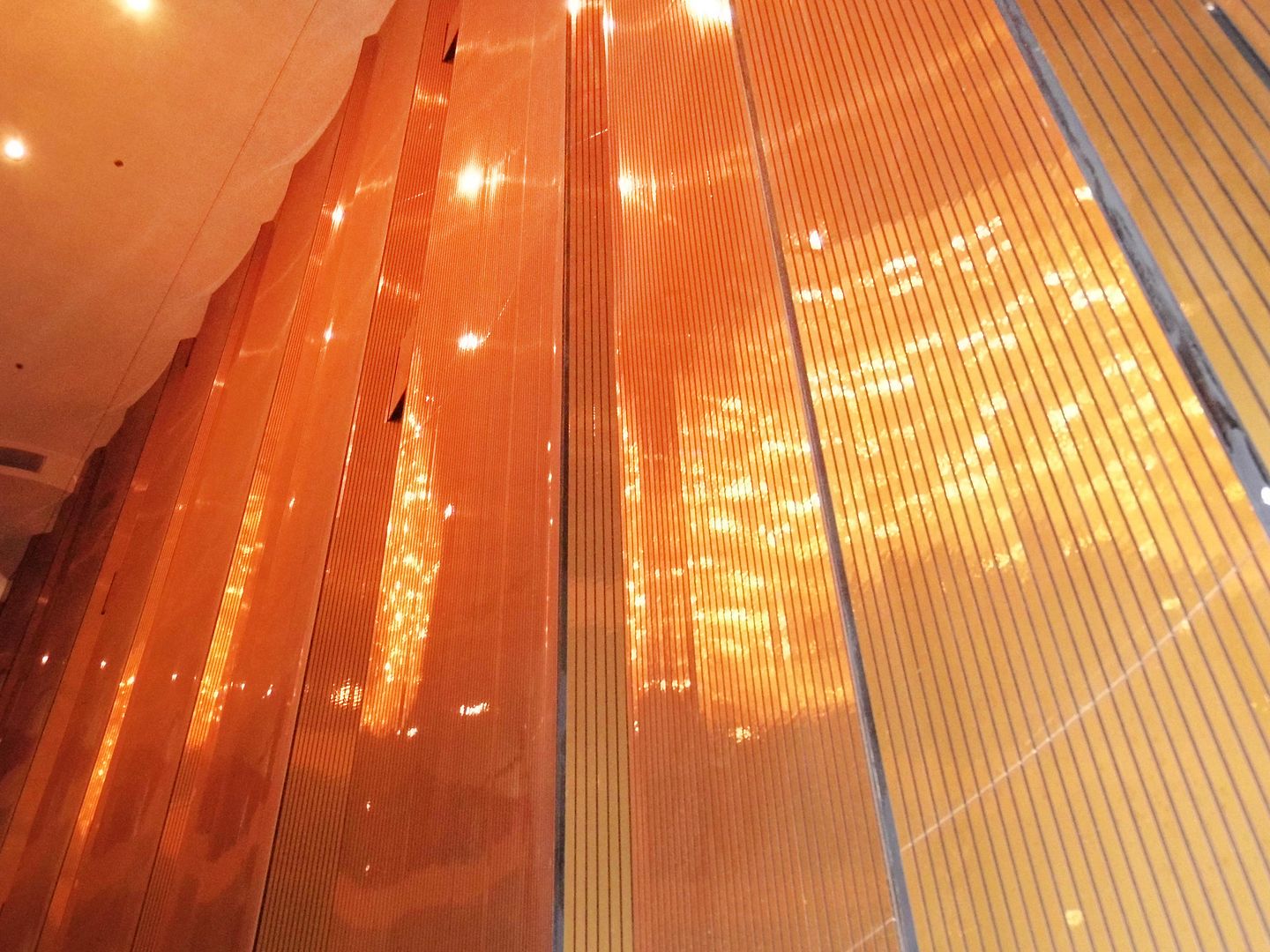

Architectural critics say that Ruocco "broke apart the box" with his curvilinear performance space and its oval façade.

Inside, the continental seating arrangement—with no center aisle—makes a big impression, especially when all 2967 seats (less so when the orchestra pit is being used) are full.

The appearance from afar is seamless—but a closer look at the armrests reveals where the rows have been stitched together.

On my tour, it struck me how huge—or, rather, deep— the stage is‚ from the proscenium line/apron to the upstage (back) wall.

Of course, it has to be in order to accommodate the Broadway touring companies and other stage productions that arrive ready to put on a show.

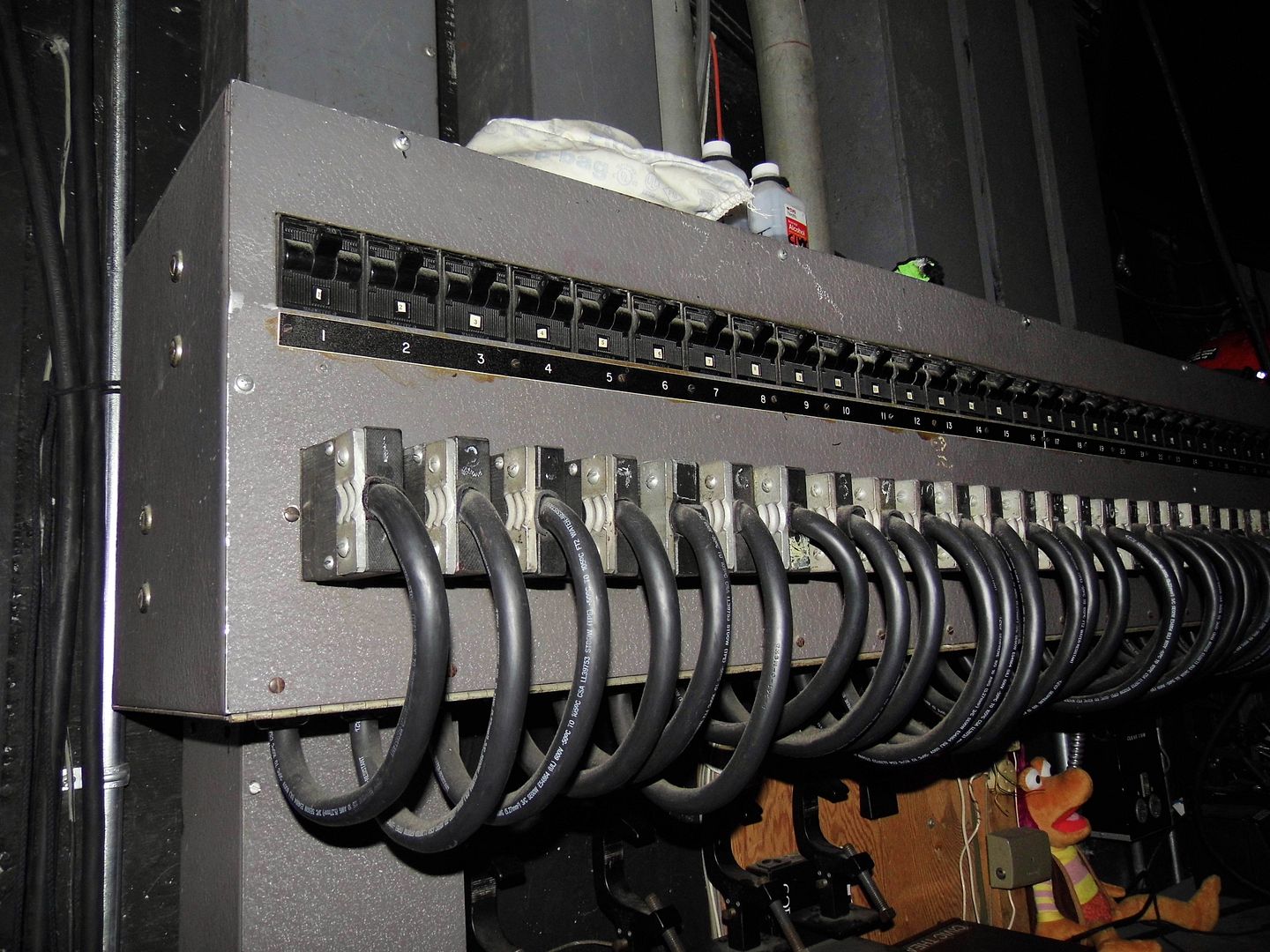

Backstage, there are also 64 sets of counter-weighted lines on steel guides and three sets on wire rope guides—installed by R.L. Grosh and Sons Scenic Studios, founded in 1932 on Sunset Boulevard in LA by scenic artist Robert Louis Grosh.

Grosh and Sons worked with all the Hollywood studios—MGM, Warner Brothers, Paramount, United Artists, Universal, 20th Century Fox, RKO, and Columbia, especially for movie musicals. They even worked with Disneyland and the Cocoanut Grove at the Ambassador Hotel.

Today, 88 years later, Grosh—now in its fourth generation, operated by R.L.'s great-granddaughter— is still known for its scenic backdrops and stage draperies

So the Civic Theatre may be lacking the obvious cosmetic grandeur of the great movie palaces of Old Hollywood—but it's not without its ties.

Then again, in 1965, some of those theatres weren't yet 50 years old and had fallen out of favor as garish or even tacky.

Early Modernism was essentially a backlash against that over-the-top aesthetic. And now, 55 years later, we're still trying to figure out how to appreciate both—and how both can coexist, without being replaced by the next new thing.

Related Posts:

Photo Essay: The 1980s Skyscraper That Ate the San Diego Fox Theatre

Photo Essay: The Art of Performing at Lincoln Center

Photo Essay: The Lima Bean Field That Became a Hub of the Performing Arts

No comments:

Post a Comment