[Last updated 1/23/25 12:29 AM PT—I had dinner at Taix tonight and can confirm it's still open, but only for dinner and only Wednesday through Sunday.]

[Updated 12/24/20 8:37 PM PT]

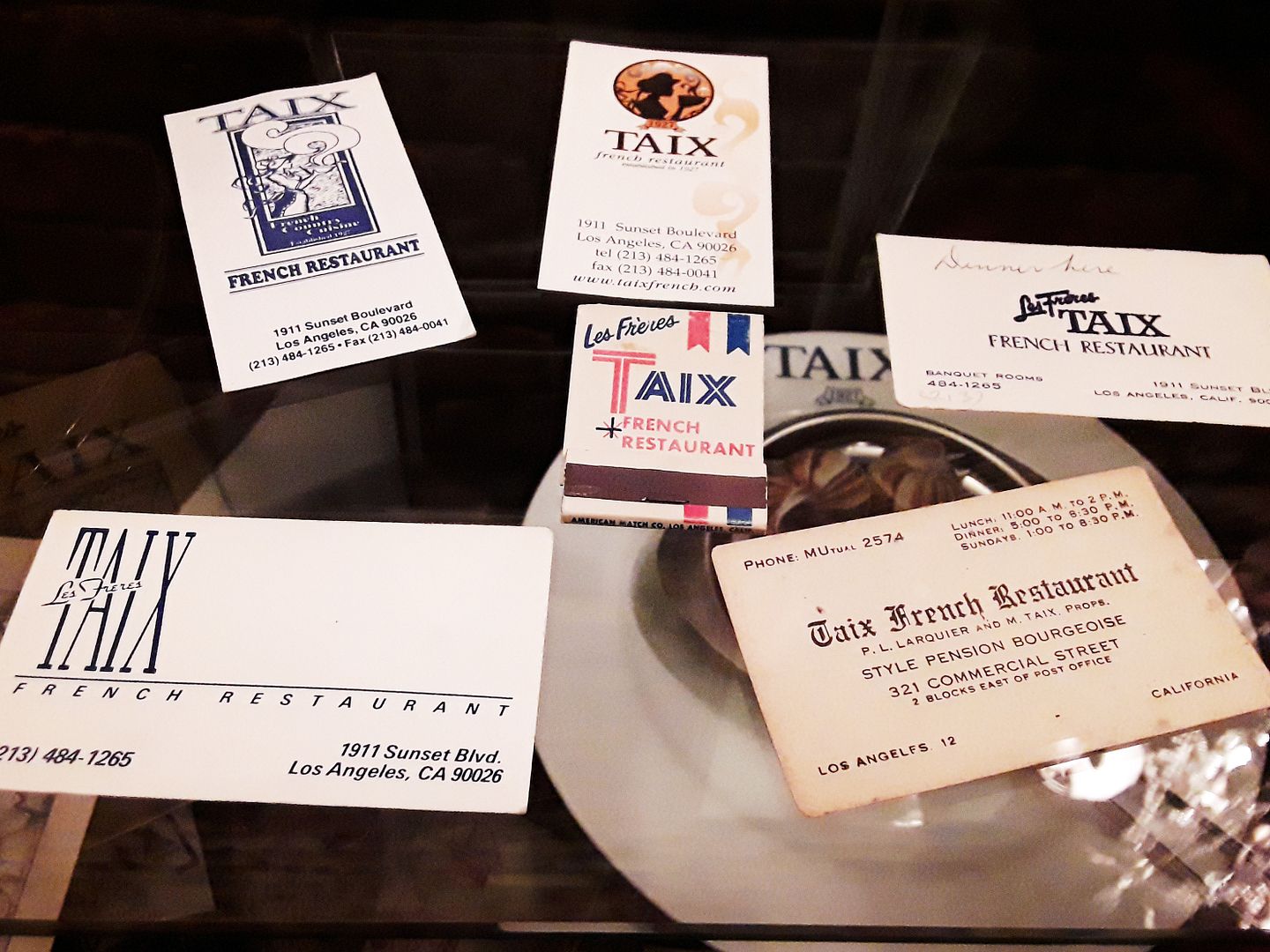

The family-owned French restaurant known as Taix (pronounced "Tex") was sold last year to Washington State-based real estate developer Holland Partner Group for $12 million. For now, Taix is leasing the building—which is slated to be torn down and replaced with a 6-story apartment complex.

This purveyor of French country cuisine is one of the oldest dining establishments in LA—an accomplishment honored by the City of LA with its rare designation of Sunset and Park as "Taix Square" in 2012.

Brothers Pierre and Raymond Taix founded it as Les Freres Taix Restaurant—though, when Raymond became the sole proprietor, the name was shortened to just Taix. Upon Raymond's death in 2010 at age 85, his son Michael fully took over and, 10 years later, was the one to sell the building (but not the business).

In a column for The Eastsider, Mike Taix wrote that the sale was to "modernize our facility and create the right sized, viable Taix... a new and improved Taix"—adding that profits aren't what they used to be and they were being swallowed up by such a huge space. "We were destined to shut down had we not decided to sell and redevelop."

Those in favor of the new development argue that the Taix building's "chalet"-style ornamentation isn't original (although the neon sign is)—and that's true. Under the gabled roofline there's a big ol' box built in 1929 that used to be a restaurant called Botwins.

But nobody remembers—or cares about—Botwins or its successor, Rafael’s. What's significant is what Taix turned the structure into—and not just by stuccoing the outside and adding some wood trim for a French Provincial look.

Nobody cares that the tin ceiling was added later, either—except that this feature is just one of the things that makes Taix Taix.

Some of the "old-looking" interior features—patinated mirrored walls, brick wainscoting, chandeliers—were actually added between the 1980s and early 2000s to reinforce the brand promise of "Country French Cuisine since 1927."

And it worked so well that now it feels as though Taix has been that way forever.

But in reality, change has been a hallmark of Taix from the very beginning—not only the renaming but also the 1969 built-out of the the porte-cochère, banquet facilities, cocktail lounge, and wine shop. It's changed so much, in fact, that Mike Taix says that "little is left from the 1969 renovation."

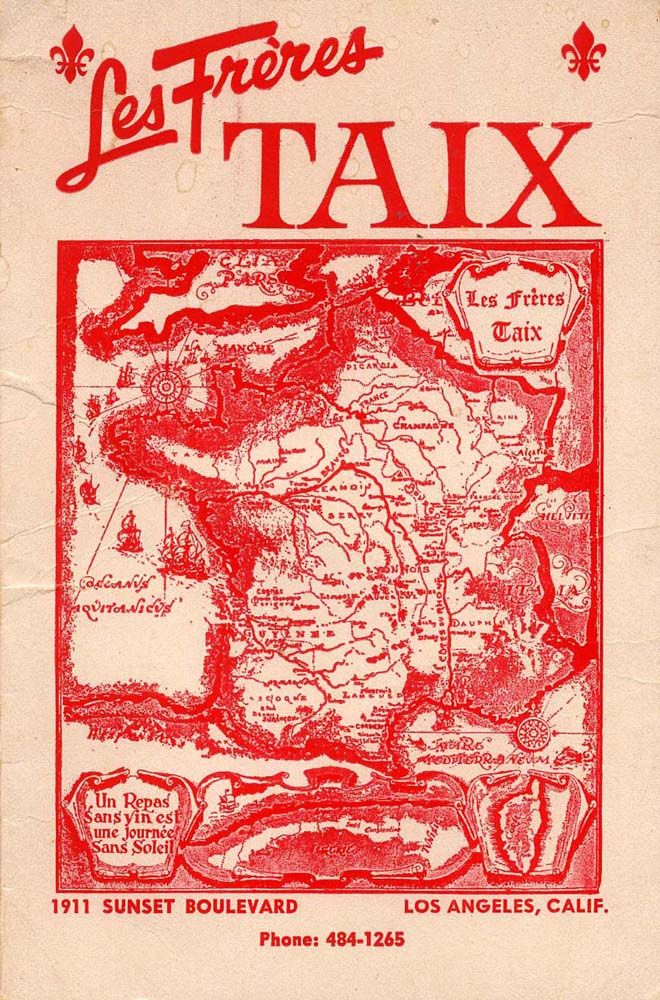

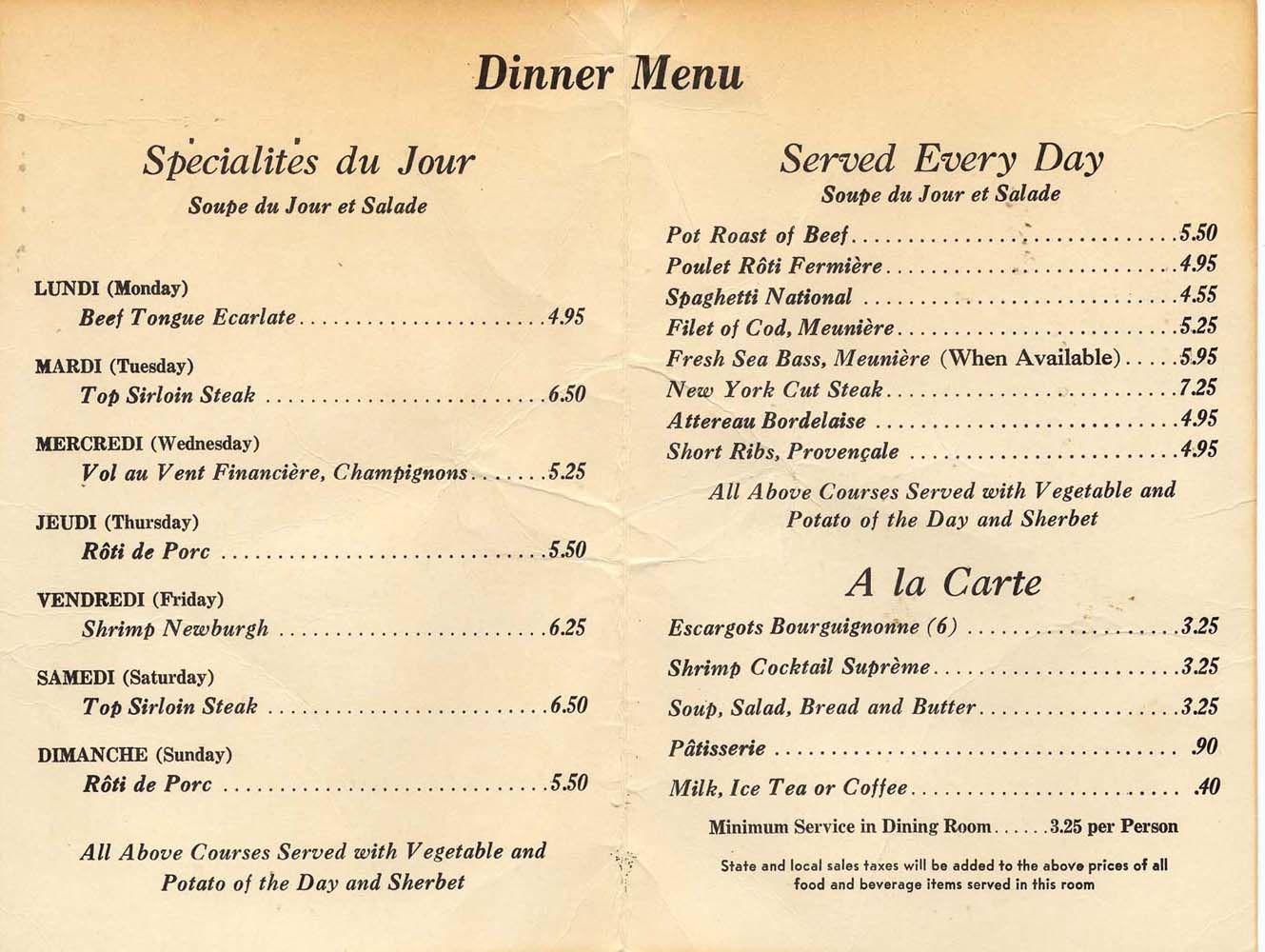

date unknown (from the LAPL Menu Collection)

Of course the menu has changed, too—for a time offering "continental" cuisine in the 1970s and '80s until it was no longer in vogue and the kitchen reverting back to French country fare.

circa 1980s? (from the LAPL Menu Collection)

But I think few historians or preservationists would ever expect a restaurant to not evolve—and to serve the exact same dishes as it did when it first opened or even 10, 20, or 30 years ago.

circa 1980s? (from the LAPL Menu Collection)

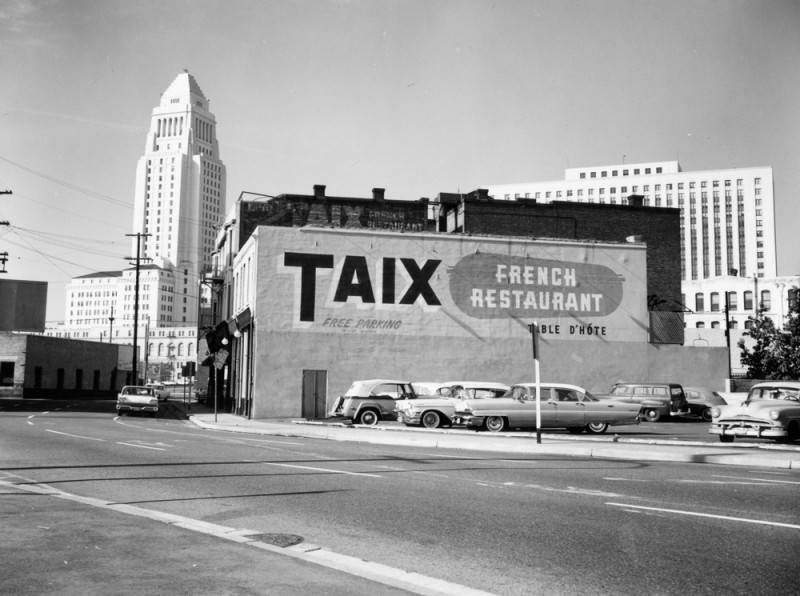

circa 1956 (Photo: Security Pacific National Bank Collection, LAPL)

And that Taix looked NOTHING like the current Taix! So why the ballyhoo over the replacement?

Well, the loss of the first Taix was somewhat of a tragedy, too—as the property was seized by the government via eminent domain. The "new" Taix was a survival tactic—with the two restaurants simultaneously running for two years until 1964, when the Commercial Street location was razed.

With its fall, one of the last remnants of LA's "Frenchtown" was brought down as well—a place where boarding house cuisine for the middle class (pension bourgeoise) was served up at bare communal tables with the Taix family's French bread and rolls in a starring role.

You see, in the late 1800s, patriarch Marius Taix and his family left their lives as sheepherders and bakers in the High Alps of France to relocate to Los Angeles—initially opening a bakery and then, in 1912, tearing down the building to replace it with the Champs D'Or hotel.

He leased a space in the hotel to a restauranteur—who, for one reason or another (there are two versions of this story), relinquished his business in 1927 to Marius Jr. (and his partner, the French-born Paul Louis "P. L." Larquier) over a conflict involving the sale of spirits during Prohibition.

According to the Frenchtown Confidential blog:

"Prohibition spelled the end for Frenchtown, since it rendered French restaurant owners unable to serve wine (the vintners had long since sold off their vineyards for development). Without wine, diners didn't want to linger at a French restaurant for an hours-long dinner."But Taix had a key exemption, as described in a 1990 edition of The New York Times:

"Marius Taix, who took over the management of the restaurant in 1927, was also a pharmacist, and he had an arrangement with a wine dealer in Oregon to supply ''medicinal wines'' to his business. This was handy for the restaurant; during Prohibition it was common to find city officials and even G-men enjoying a lunch with wine in the back room of the establishment."While some reports claim that some nearby government office buildings lacked cafeterias, an article in the February 2003 newsletter of the Los Angeles City Historical Society (for which Taix has served as a second home for decades) states:

"The attraction was not so much that there was little competition in the way of eating places in the area, but primarily the aroma coming from the self-serve soup tureen placed in the center of each table. The taste lived up to the anticipation, as did the sour dough bread [sic] and salad that accompanied the meal."And then there were the 50-cent chicken dinners (later 60 cents)—with private booth service offered for an extra 25 cents.

Although the current Taix offerings are moderately (or even modestly) priced, the soup tureens now make the rounds accompanied by impeccably dressed waiters, who'll be sure to not dribble any on your white tablecloth.

After Prohibition ended, the wine selection came back in full force—with some vintage versions of the menu declaring, "Un repas sans vin est une journée sans soleil" a.k.a. "A meal without wine is a day without sun." The Taix wine list is still considered world class—and reasonably priced.

Sure, there are some old-timers who surely remember "old" Taix in Downtown LA. But to many, "new" Taix is the only Taix they've ever known. The premise of the new new Taix—at 6,000 square feet, about a third of the size of the current restaurant—is simply abhorrent.

And it's not just aesthetics—though pretty much everybody in the community hates the proposed renderings. It's also the matter of an accused "bait and switch"—the fact that a partial preservation of present-day Taix was promised, yet the current plans show little-to-no preservation of historic elements.

Preservation, of course, is subjective. Much of what the City of Los Angeles places historic value on is for a cultural impact. It's tough to pick and choose which physical elements on their own are historic—because it's the entirety of the place, in aggregate.

For many, it's too heartbreaking to see Taix reduced to a mere footnote in a behemoth residential development. It doesn't look like a place that anyone nostalgic or sentimental for either Taix #1 or Taix #2 would want to go to. I mean, that amuse-bouche of carrots, radishes, and scallions isn't that good.

But, as one LAist post bemoans, "Real estate has no room for sentimentality."

A newly-formed organization called Friends of Taix launched a petition to try to save the current version of the restaurant, which is no longer accepting signatures.

Update: Although the development seems like a done deal, the Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Commission voted unanimously to recommend it be designated a Historic-Cultural Monument. The next step is for it to pass through City Hall.

- To read a comprehensive history of Taix and LA's "lost French Quarter," click here.

- For an excellent recap of Taix's architecture and images of the building before it was Frenchified, click here.

Will Shamrocks and Horseshoes Bring Enough Luck to Keep Tom Bergin's Open For Good?

No comments:

Post a Comment