Over 3,000 hand-carved, wooden carousels were manufactured at the Herschell Carrousel Factory in North Tonawanda, New York.

That was from 1915—when it moved into the former home of King Lumber Company—until 1953, when the company was sold and moved from the suburbs into the city of Buffalo proper.

The location was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985—even though the Herschell Company had been sold again in 1970 and moved even farther away, to Kansas.

In 1997, Chance Manufacturing (later Chance Rides), sold its Herschell holdings to the Carousel Society of the Niagara Frontier—and now that the company has moved back home, it currently supplies parts and provides support to 900+ antique Herschell rides (and their operators) around the world.

The whole complex is miraculously intact—although the roundhouse is a replica of where carousels were once assembled and tested. It's now home to the #1 Special carousel circa 1916.

The former factory was transformed into a museum in 1983, giving public access to the former factory—including original workspaces like the carving room. That's where beginner/apprentice carvers (a.k.a. "legmen") would work on the horses' legs; "journeymen" would carve the hollow bodies as well as saddles and bridles.

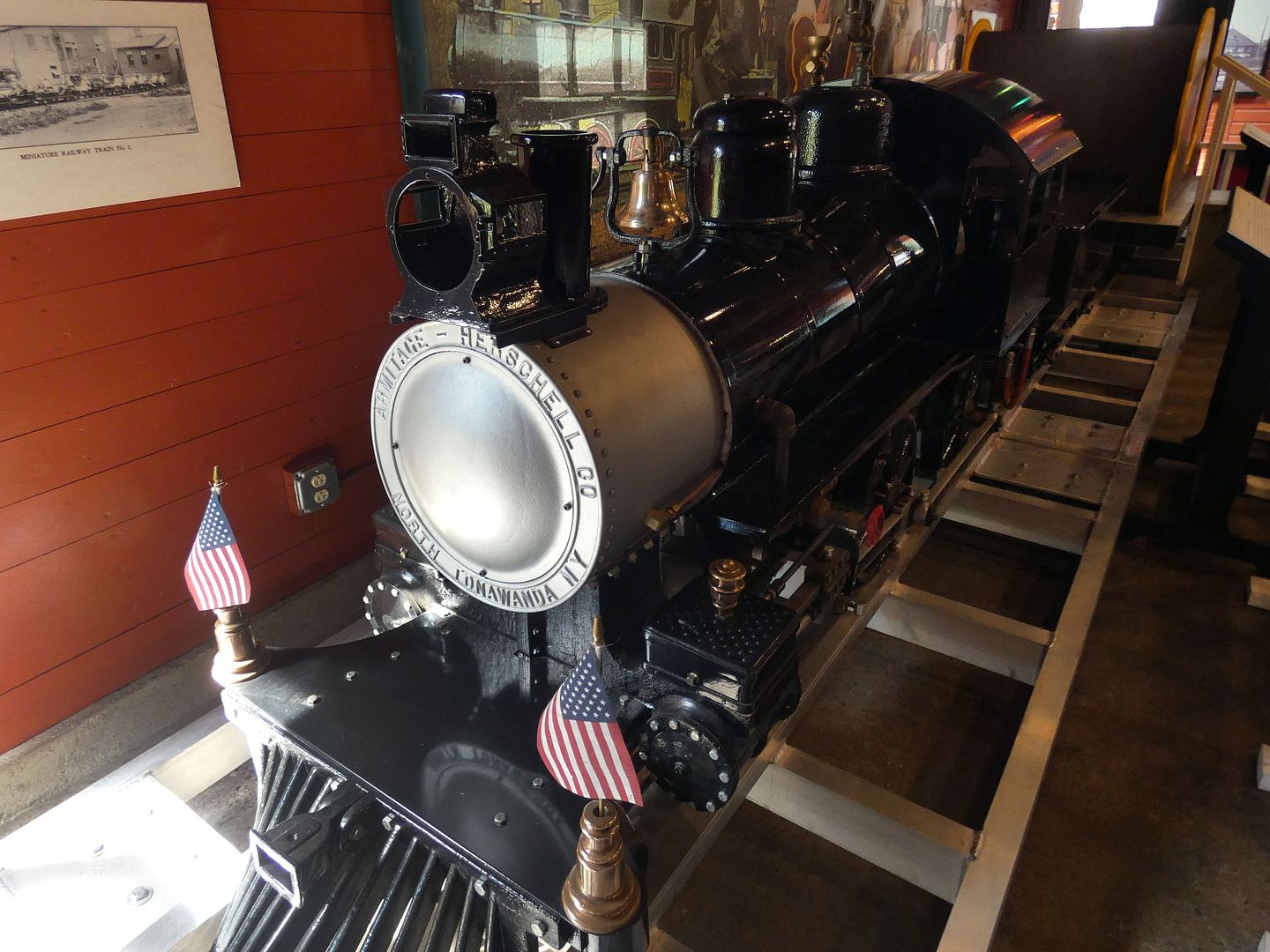

circa 1880s, Armitage-Herschell Company

Master carvers would take charge of the heads and necks and assembling all the parts into a single horse (including adhering them together with hot horse hide glue). They also designed new animals—including ones they may have never seen before in person, like a kangaroo or an ostrich.

In the former paint shop—now a gallery of freestanding carousel horses and menagerie animals—carved wooden horses got several coats of white primer before getting their color schemes, and then seven coats of varnish to top them off.

Menagerie animals included bears, giraffes, roosters, boars, dogs, and more.

And while most of them had saddles carved into the figures just like the regular horses did, Herschell left the saddles off the zebras. Individual carousel operators might add one on to encourage people to ride the animals, which they figured out most wouldn't do without a saddle.

The Herschell Factory had a very fast output via its assembly line —and so, it was able to produce extra horses to be used as replacements when a horse on one of the operating Herschell carousels broke, wore out, or otherwise needed to retire. These "spares" were boarded in a "holding pen" on the factory's second floor, where the upholstery shop also was located (for seating in chariots), now closed to the public.

The paint shop is also where carousel scenery panels and rounding boards, cornices, and shields were painted by hand.

And today, this room is another place where you can really see the difference between the "old" style of Herschell carousel horses (with the perked-up ears and friendly faces) and the style they evolved into, with pinned-back ears and more dramatic facial expressions.

Over time, the carousel horses became more elaborate, too—with the saddles carved right into the bodies, carved tails (instead of those made out of real horsehair), and blankets, pelts, and other accessories in different patterns (some in patriotic color schemes).

In addition to their glass eyes...

circa 1920s, Spillman Engineering Corporation

circa 1920s, Spillman Engineering Corporation...they were also later outfitted with a number of multi-colored gems and jewels (usually on the outside-facing side, or the "fancy" side) to catch the eyes of would-be riders.

The museum's gallery even has one carousel horse circa 1920s that never made it onto a carousel—but did get turned into a rocking horse.

Part of the Herschell Factory Museum's musical collection—because every carousel needs music—is the Style "D" band organ manufactured right in North Tonawanda in 1925 by Artizan Factories, Inc. (1922-9). The museum acquired it in mint condition (a.k.a "as-built" factory condition) in 2014.

Artizan was one of several competing musical instrument manufacturers in the area, which was blessed with plenty of cheap raw materials—like wood and paper—plus access to the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes, and an extensive rail system, all of which made shipping out of the area to the rest of the world relatively easy.

There was also Wurlitzer (whose band organ and music roll department was purchased by Herschell in 1945)...

...North Tonawanda Musical Instrument Works (1906-18), Niagara Musical Instrument Works/Manufacturing Company (1905-14)...

...and North Tonawanda Barrel Organ Factory (1893-1903) (which became de Kleist Musical Instrument Works, 1903-9), all of which revolutionized the industry, which had been importing its band organs from Europe.

On display at the museum is also perforator #12 from the nearby Wurlitzer factory. Wurlitzer military band organs used perforated paper rolls (with holes punched in them) to play their music—a mechanism that was cheaper and more convenient than barrel rolls used by other companies. Perforation helped Wurlitzer edge out its competition by 1929—but by 1930s, the 78 rpm record had edged out the paper rolls (hence Wurlitzer's foray into the jukebox market).

In the Children's Gallery (the factory's former machine shop, where metal cranks, gears, and more were produced), there's yet another antique carousel that's up and running—but this one is just for the museum's junior-sized visitors.

The 1940s-era "Kiddie Carousel," restored in 1981, was originally designed on a smaller scale so children could ride it without having to be accompanied by an adult (which they would for a full-sized version like the #1 Special carousel).

This pint-sized amusement features two rows of 20 "kiddie jumpers"...

...tiger- and mermaid-themed chariots (made with non-original carvings)...

...and shields that are just as ornate (and slightly disturbing) as you'd find on an "adult" carousel.

In fact, carousels began as adult amusements—but as the target age shifted downwards, so did the focus of the Herschell company as it developed more "kiddie rides," like the Armitage-Herschell steam train #1. It operated at Centre Island, Toronto for over 40 years and seats 8 adults or 12 children.

Kiddie rides thrived in the post-WWII "baby boom"—and Herschell's contributions to the industry starting in the 1940s are represented in the "Kiddieland Hallway" at the museum, featuring the "Little Dipper" junior steel rollercoaster from Crystal Beach Park on the Canadian side of Lake Erie, where it resided until the park's closure in 1989.

Just outside, you can find working models of four different Herschell Kiddieland rides, all originally built right here in this factory, in the outdoor Kiddieland Testing Park exhibit.

This part of the museum opened in 2013—and it's where children can "test" restored company rides from the 1950s, three of which were relocated here from Page's Whistle Pig Restaurant in Niagara Falls, New York (now closed).

I can't believe I grew up just 150 miles east of this place and never even knew about it until after I'd already moved across the country!

It just goes to show how much making up for lost time I've still got to do.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment