What appears to be a simple restaurant and tea room in Pasadena, California has a much richer history than meets the eye—one that involves the "foremost designer of residential interiors in Southern California in the 1920s" (according to late architectural historian Robert Winter), military secrets, and maybe even Albert Einstein.

Located in what's now known as the Green Street Village Landmark District, it's currently known as Madeline Garden—but it was designed in 1927 in the Georgian architectural style by Louis du Puget Millar as a studio/office/workshop for renowned interior decorator Edgar James "E.J." Cheesewright and his staff of craftspeople and artisans (including woodcarvers), decorators, and furnishers.

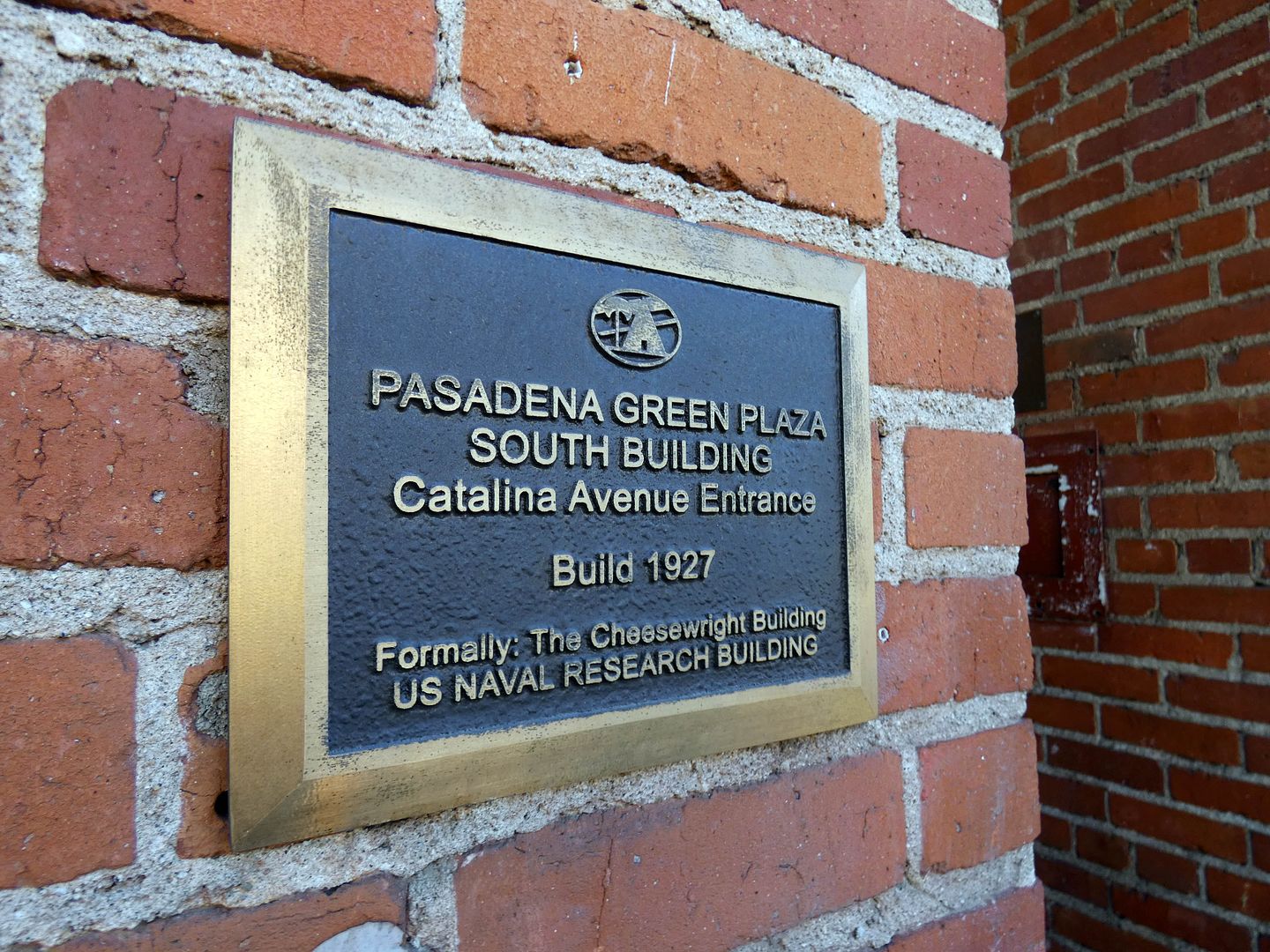

Constructed out of bricks that were originally painted white and surrounded by green trim, it started out as The Cheesewright Studios Building...

...located in Pasadena for its proximity to Millionaires Row and its built-in clientele.

Enter through a French Quarter-style garden court with red flagstone pavers and a porpoise fountain...

...where one of the wrought-iron balconies still features the Cheesewright Studios initials (though it's been painted white).

The 30,000 square-foot structure (an upgrade from the space at 322 East Colorado Boulevard the business had outgrown) originally featured three boutiques facing the sidewalk...

...and at the eastern wing of the building and along its south façade, you can see what it looked like painted white...

...in contrast to the west wing and north façade, which were later sandblasted to expose the red brick underneath.

Born in London, Cheesewright made a name for himself in the United States with his renovation of the White House—and in California through his work on the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, Greystone Mansion, Hearst Castle, Walter Temple's La Casa Nueva (part of the Workman-Temple Homestead Museum), and more.

loading dock

The Great Depression, of course, hit the business really hard—and Cheesewright only operated out of his studio building until 1936, when architect Louis du Puget Millar moved his practice into the building.

loading dock

In 1943, Caltech students moved in to conduct research from the offices therein—and that's when things started to get really interesting at the Cheesewright Studios Building.

In 1946, the U.S. Naval Research Bureau (a.k.a. the Office of Naval Research, and its Engineering Support Office) took over ownership of the building and, from there, operated a branch (a.k.a detachment) of its Navy Undersea Research and Development Center—the naval division responsible for developing the Sidewinder guided missile, among other weapons (especially underwater ones, like those for anti-submarine warfare), in coordination with what was then the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS) in Ridgecrest (now NAWS China Lake).

The Green Street location was conveniently located less than a half-mile away from Caltech, where researchers were working on rocketry, nuclear physics, national defense, and more. But it wasn't the Navy's only Pasadena location—there was also an annex located about 3 miles east (the "Foothill Plant," in what's colloquially known as East Pasadena). And Navy Undersea R&D staffers also conducted tests in the foothills above nearby Azusa at the former test range site at Morris Dam.

There's a legend that Albert Einstein (a Caltech visiting professor in the 1930s) had some kind of secret office in the basement of the old Cheesewright Studios building—one that was connected to Caltech by underground tunnels (subsequently sealed off).

Local historians, however, claim it was Albert Einstein's son, Hans Albert Einstein—who worked as a research engineer at Caltech from 1943 to 1947, as well as briefly for the Office of Naval Research. Maybe Vater Einstein visited his son at work—because the Navy didn't even move into this building until three years after he'd consulted part-time on torpedoes for the Navy's Bureau of Ordnance (the predecessor to the Bureau of Naval Weapons), in 1943.

No civilians have verified the existence of that rumored tunnel (though there are some verified ones on the Caltech campus). But we do know that the Western Regional Office of the ONR at 1030 East Green Street was involved in researching oceanic engineering. The most documentation of it comes from the declassified ONRWEST reports of the Arabian Sea Project (circa 1980), including the development of infrared imagery as part of the Navy's satellite mapping efforts in foreign waters.

Of course, none of that is evident when you enter the Cheesewright Studios today. The naval detachment was moved to Boston after the 1987 Whittier earthquake created enough structural damage for them to vacate the premises—and for the Navy to auction it off in 1990.

In case of another earthquake, the building has since been retrofitted for seismic stability—some evidence of which is visible in the 2-story, open-air atrium off the entrance hall.

That lobby is how you get to both Madeline Garden and the Pasadena Green Plaza Apartments upstairs—with residential units accessible by an original curved staircase (above which hangs what may be an original chandelier).

lengths 1-24

At the top of the stairway is a mural of painted wallpaper by French company Zuber et Cie, which still manufactures a number of different scenic papers created by the process of woodblock printing (a.k.a. "à la planche"), using antique blocks carved in wood all the way back in 1834.

length 24

This one is a 4-panel, 32-length panorama called "The Views of North America" (a.k.a. "Les vues d'Amérique du Nord," or "Scenes of North America"), created by French artist Jean-Julien Deltil—who likely never visited the "New World" and instead relied on stereotypes and, some say, racist tropes and insensitive cultural depictions.

a section of lengths 15-23

A more famous version of this same woodblock-printed image can be found in the White House, first installed when First Lady Jackie Kennedy redecorated the Diplomatic Reception Room. The Obamas have famously been photographed in front of it many times.

Other intact decorative and architectural features of the Cheesewright Studios building—despite its deacades-long naval occupation—include brick arches, bay windows, carved doors, and interior transom windows (to encourage air circulation in the time preceding air conditioning).

While fully furnished showrooms were located on the first floor, offices were upstairs—and a freight elevator (with a fire door) helped move larger items around the building. Cheesewright was a collector and seller of European (especially French) antiques—some of which may have been stored in the extant walk-in safe by Diebold Safe & Lock Co. of Ohio (on the lower level).

Cheesewright Studios also dealt in its original creations—much of which were fabricated onsite in its own cabinet shop, furniture shop, upholstery shop, and wrought iron shop (for balconies, gates, etc.).

Most of that activity occurred in the back of the ground floor of the building, which explains the warehouse look of the rear exterior as well.

In addition to the showrooms, the "front of house" areas of the Cheesewright Studios building's street level included eight sales rooms and Cheesewright's executive office (below).

Above: Virginia "Ginny" Hoge, historian and tour guide

Originally paneled with knotty pine, it also featured an antique Georgian fireplace mantel from England—which is still there, now nearly 245 years old, and can be seen in the Season 4 episode of Mad Men titled "Public Relations."

Although today there are other tenants in the former storefronts—as well as the residents upstairs—much of the former Cheesewright Studios space has functioned as one restaurant or another since 2001, including Chef Claud Beltran's Restaurant Halie.

Madeline Garden has been serving tea out of the space since 2013—and its main tea room now occupies the former Cheesewright main showroom (later, the naval conference room), with its original and still-working fireplace.

During my recent visit, our small tour group took our traditional English tea service in that room, under that 20-foot ceiling...

...sipping on oolong and passionfruit tea as we nibbled on scones and quiche...

...various toasts...

...and tiny sandwiches of the vegetarian and chicken salad sort.

E.J. Cheesewright was an important interior decorator of the early 20th century—but over the last 100 years, his name has been forgotten and his reputation has faded. Formerly a luminary of the Arts and Crafts Movement, he's been eclipsed by architects like Greene and Greene and specialists like Batchelder.

But what Cheesewright did—much in the tradition of the Roycrofters—was provide one-stop shopping for his residential clients. And he did it in a way that potential customers could see the windows, doors, railings, and cabinetry in situ—so they'd know exactly what they would look like in their own homes.

He also made his studios a family business—employing his son, Robert Warner Cheesewright, to help design kitchens for a period of time.

In 2003, at the age of 90, Bob himself wrote a letter to the Los Angeles Times editor expressing his surprise (and, if you read between the lines, his disappointment) that the paper hadn't mentioned his father at all in a profile on Greystone Mansion they'd published—despite his extensive work on it.

The Times ran the letter. But not much has changed since then.

In fact, it's the Einstein tunnel rumor that seems to have piqued most of the media interest in the Cheesewright Studios building (at least, what little there has been)—and not the man who lent his name to it.

Maybe that's OK—because it was the Einstein tunnel story that brought me to The Cheesewright Studios Building and Madeline Garden for a tour and tea. And I ended up getting a lot more out of it than just unproven rumors of a secret underground lair.

Further Reading:

The Secret History Of The Pasadena Restaurant That Was Once An Atomic Bomb Research Site—LAist

Historic Building Sold at Auction—Pasadena Star-News (via Pasadena Public Library)

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment