I think I first heard about it when it was undergoing a restoration (and earthquake retrofitting), sometime between 2015 and 2017. I kept my eye on it—and finally managed to take a tour in 2018.

L-R Observatory, library (Photo: Security Pacific National Bank Collection, via LAPL)

If you don't know Clark by name, you probably know the legacy left behind by his father—the copper baron William Andrews Clark, Sr. who bribed his way into becoming a U.S. Senator and ended up with Clark County, Nevada being named after him.

Clark Jr. was born in Montana in 1877—and although he died there in 1934, he's buried in a tomb on the island in Sylvan Lake at Hollywood Forever Cemetery. In his will, he bequeathed his 18,000-square-foot, Beaux Arts-style library and its collections to the educational institution that would become UCLA—and stipulated that it be named not after himself, but his father, who'd passed away in 1925.

Built using bricks from the still-operating Pacific Clay Products in Lake Elsinore, CA, the Clark Library was completed in 1926—three years after a fire in the main house shook Clark Jr. up enough for him to relocate his already-extensive and growing book and papers collection to a new and separate library, which he insisted be built under best practices for fire-proofing as well as temperature and humidity control, ventilation, and even survival of a seismic event.

vestibule

When you walk into the library's European marble-floored and -walled entrance foyer, the barrel-vaulted ceiling (pictured below) features a mural in honor of Apollo, the god of music, painted by Allyn Cox (of U.S. Capitol fame).

vestibule

It's an appropriate tribute, considering Clark Jr. (heretofore referred to as just "Clark") bankrolled the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the construction of the Hollywood Bowl—but a closer look reveals that there's even more going on here, as all 13 bodies have the same man's face.

It's the visage of Harrison Post, Clark's lover and partner—who also served as "assistant librarian" and even helped transcribe Oscar Wilde's handwritten letters to Lord Alfred Douglas.

drawing room a.k.a. the music room

Post inherited quite a fortune from Clark—but not the library, which reportedly he'd been in charge of decorating (with some exceptions, including the vestibule ceiling, which was all Clark's doing).

drawing room ceiling, carved out of English oak by Baumgarten Interiors & featuring depictions of John Dryden’s play, All For Love, painted by Allyn Cox

drawing room ceiling, carved out of English oak by Baumgarten Interiors & featuring depictions of John Dryden’s play, All For Love, painted by Allyn CoxThey lived—and loved—in secret (hence the title of Liz Brown's book on the relationship, Twilight Man).

drawing room (Henrique Medin portrait of Robert E, Cowan, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library's first librarian hired in 1919)

drawing room (Henrique Medin portrait of Robert E, Cowan, William Andrews Clark Memorial Library's first librarian hired in 1919)But it's likely that people in Clark's circle knew that he had affairs with men after his wife Alice died in 1918 (and maybe before that, too?).

Today, the library is all that's left of the Clark estate for the public to wander through. His home (circa 1906) and copper-domed observatory tower (pictured at the top of this post) have been lost to history, the former of which was demolished in the wake of the 1971 Sylmar earthquake.

But the library, designed by architect Robert Farquhar, is triumphantly intact—including its trompe l'oeil paintings, coffered ceiling, and amber glass clerestory windows (by Judson Studios, no less).

The bookcases are unusually made of bronze—an alloy of copper, perhaps an intentional hat tip to the source of his father's fortune.

Although I visited the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library more for the building itself and the history of its former owner, many visitors are drawn to the library's collections—and not just its Oscar Wilde holdings.

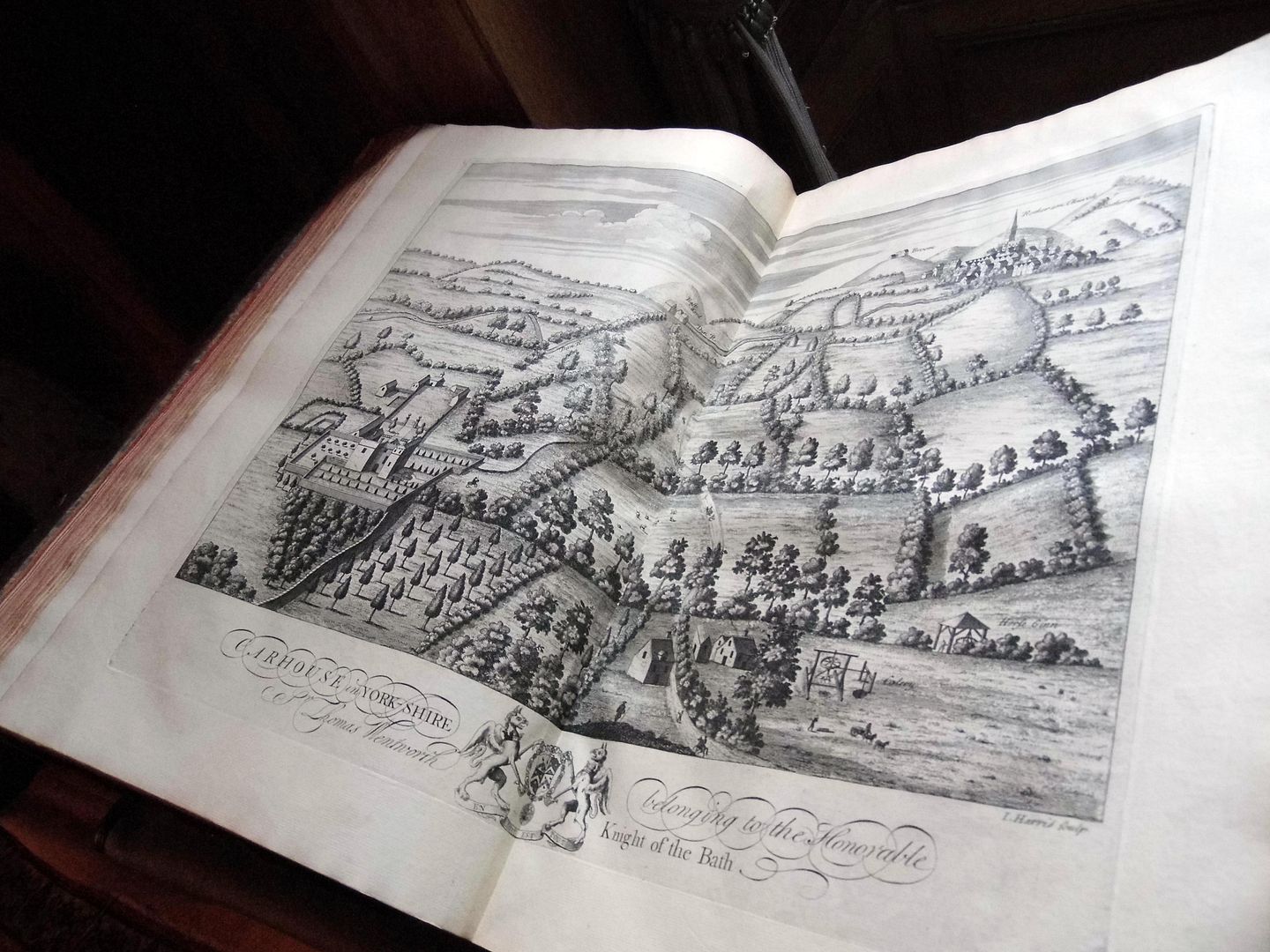

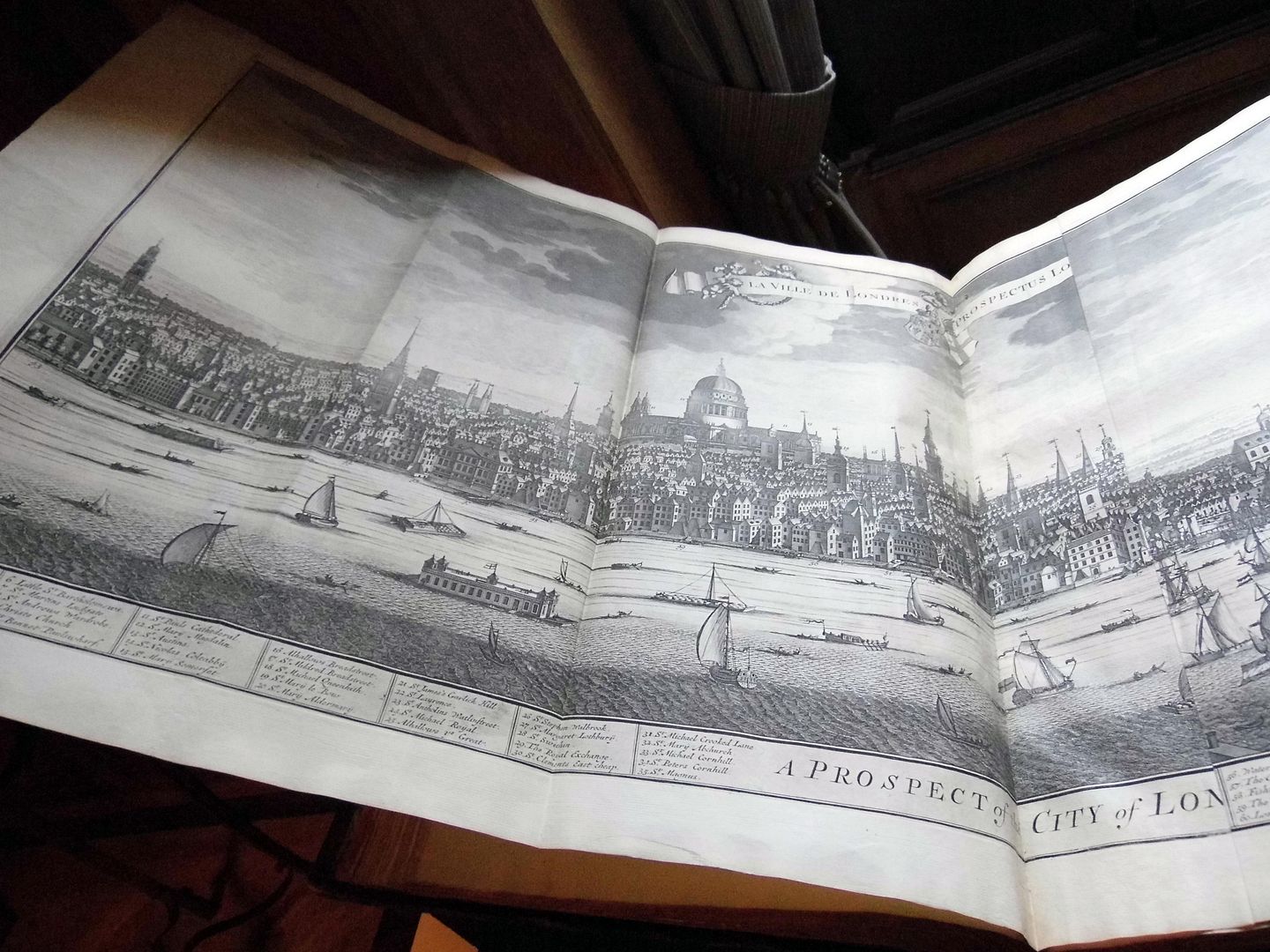

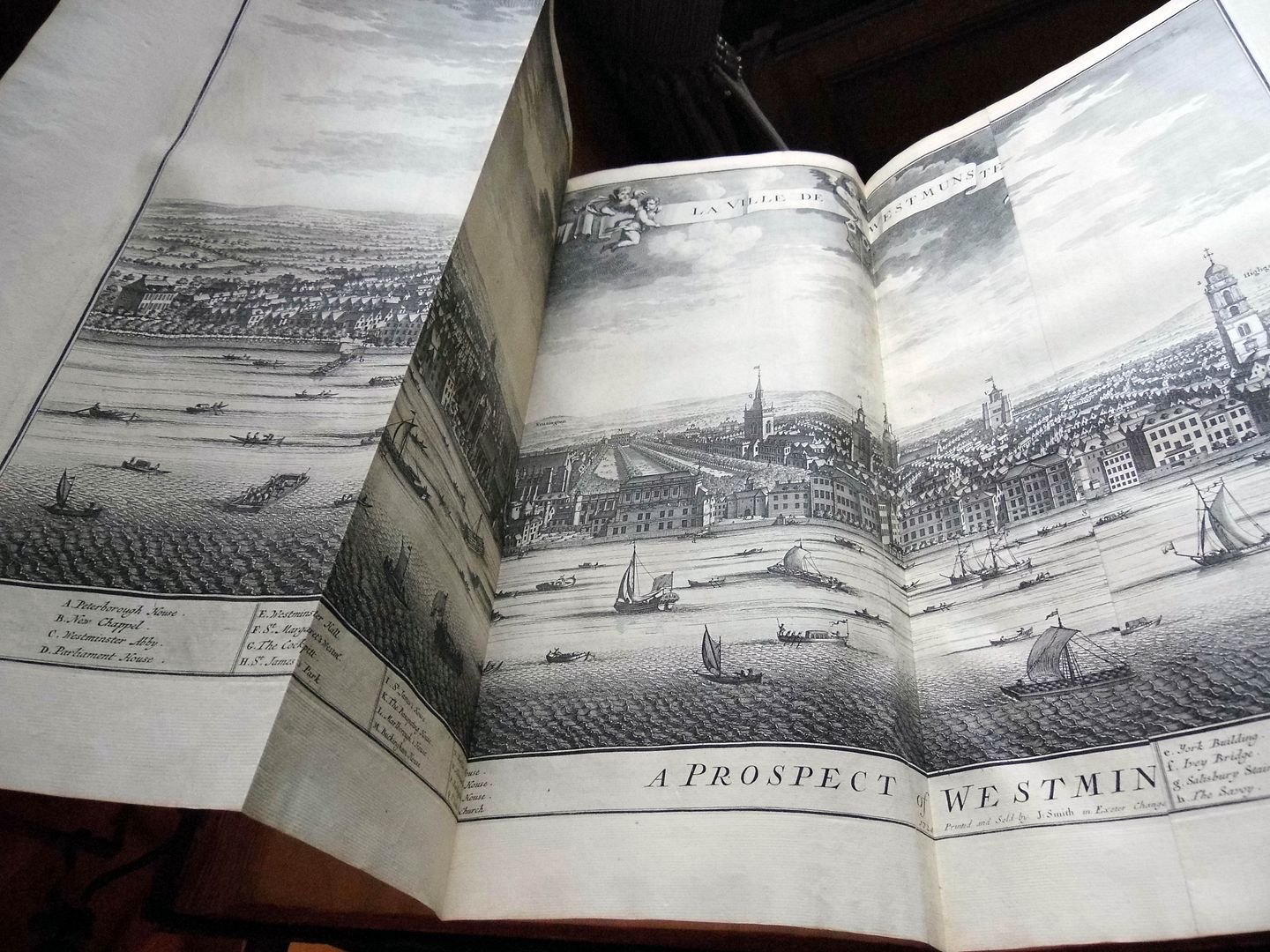

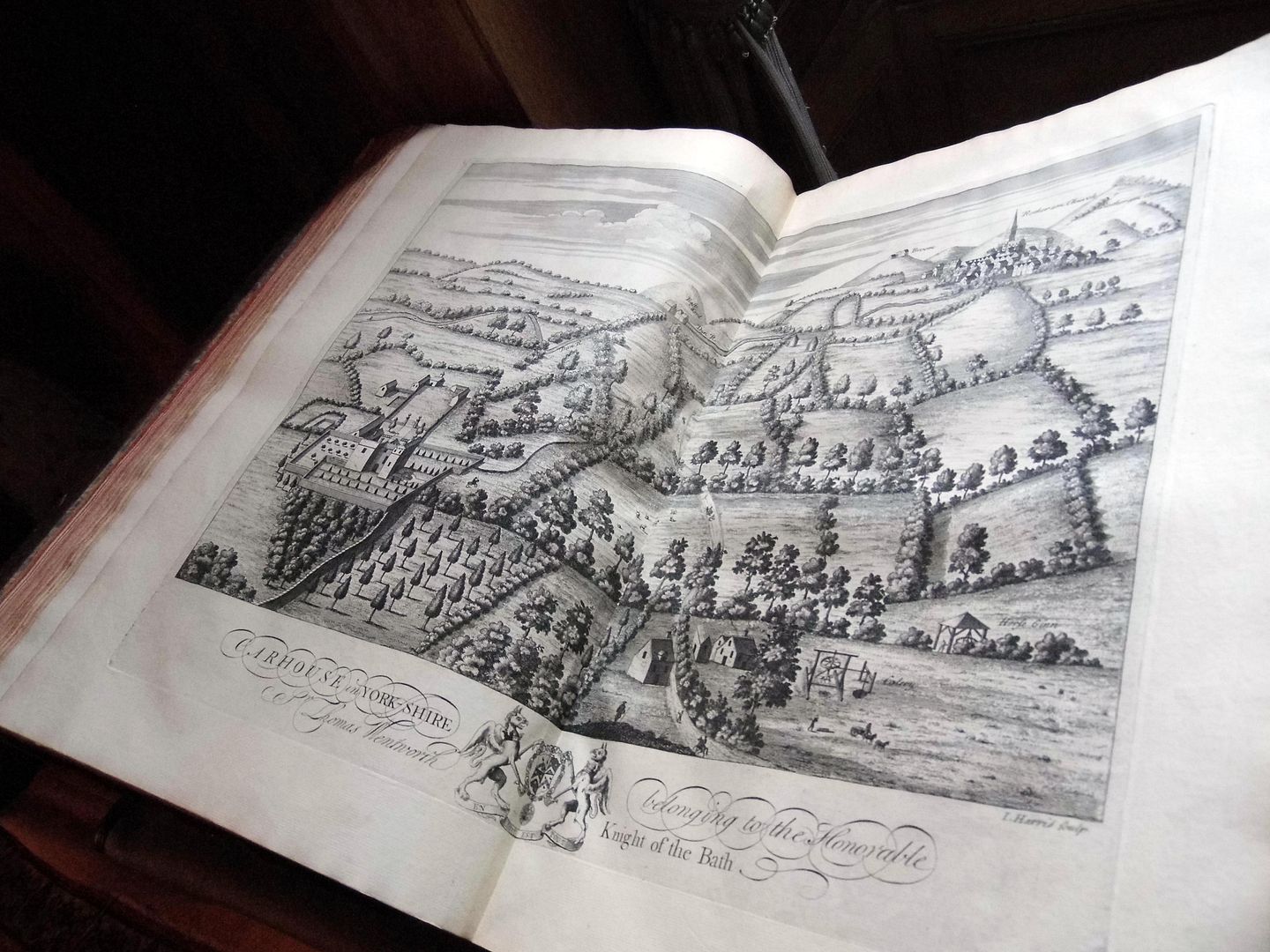

During our tour, we got to examine fold-out pages of plate books, featuring 18th-century engravings by Johannes "Jan" Kip included in his Britannia Illustrata...

...which was later expanded into what would become known as Nouveau théâtre de la Grand Bretagne (circa 1724).

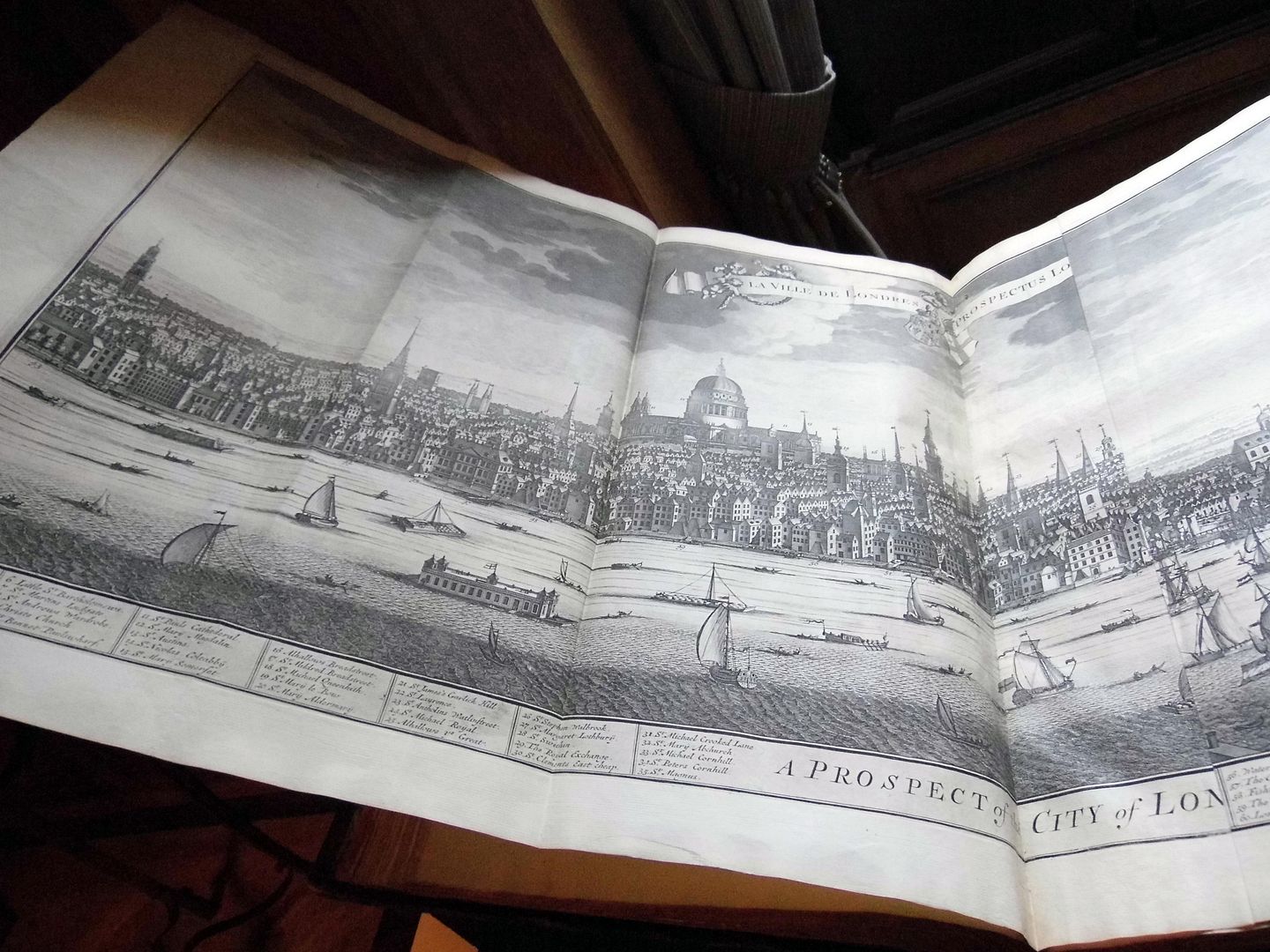

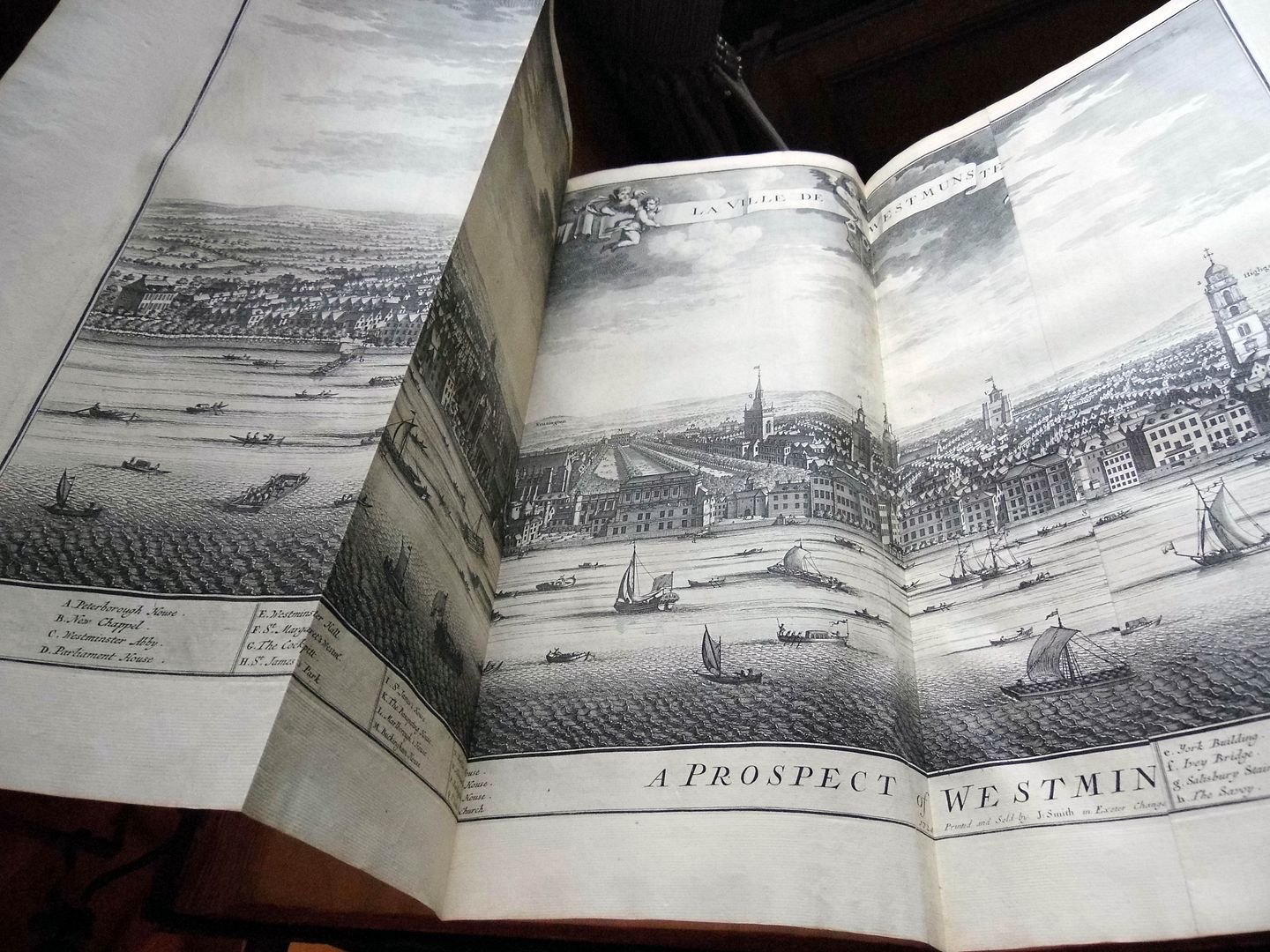

Among the historic architectural surveys of the time, these engravings—including "A Prospect of Westminster and A Prospect of the City of London" (circa 1720) and "The West Prospect of the Cathedral of York" (above, circa 1724)—are considered some of the most important.

Much of Kip's work—including his birds'-eye-view depictions of Wentworth Castle and its grounds in South Yorkshire, England—were based on the drawings of Dutch draftsman Leonard Knyff.

There are two library rooms inside the Clark Library main structure—but its facilities for literature lovers don't end there.

There's also an "outdoor reading room" immediately adjacent to the building's south side (walled off from West Adams Boulevard)...

...featuring gargoyles carved out of Roman travertine...

...and other sculptures and ornamentation that underwent some conservation work during the library's multi-year closure.

I'm not sure how much reading goes on there, but the library does occasionally host lectures, concerts, and other events in the outdoor reading room.

Since 2002, this outdoor space has also been home to the sculpture known as "The Face of Copernicus"—cast from the original mold that New Deal-era American artist Archibald Garner used in 1934 to create Griffith Observatory's Astronomers Monument.

There are plenty of examples of public art throughout the grounds—including such bronze sculptures as Sherry Edmundson Fry's "Boy With Seashell" and Clare Consuelo Sheridan's "The Birds" (above, circa 1929).

But I found myself particularly drawn to the gatehouse, located across the parking lot from the library (which is the centerpiece of a nearly 5-acre site, with no other structures within 100 feet of it, per Clark's will).

The 4,206-square-foot structure predates the library by decades—it was added to the grounds in 1906—and it's the only other architectural remnant contemporary with William Andrew Clark, Jr.'s lifetime (other than the brick wall that surrounds the property).

It's currently used as storage by the groundskeepers, but it was once home to The Press in the Gatehouse—a printing house that churned out small editions created by printer-writers being hosted by the Clark Library (through at least the 1980s).

Before that, it was the servants' quarters. And although it's not in its original location, it still stands today where Clark himself had it moved.

There's been some talk of restoring the Clark Gatehouse so it can become a UCLA-run book arts center—but I haven't been able to find any update on the project more recent than 2014.

Of course, if there's any chance of getting inside—either now or later—you know I'll be first in line.

All photos above circa 2018 except where noted.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment