I've been attending San Diego Architectural Foundation's Open House San Diego for the last few years—even squeezing in a visit a little over a week before everything shut down in 2020.

But this year was different—not because of the pandemic, but because my car has been sitting in the shop (essentially undrivable) since January 17.

I've been getting around on foot and via public transportation (like a good former New Yorker). But that was going to put a cramp in my style somewhat for Open House San Diego.

I knew I could take the Amtrak down to Santa Fe Depot no problem—and that the trolley could get me around to lots of places. But I wouldn't be able to cram very much into one day.

So, I agonized over having to limit myself to just one general area—and having to choose among the dozens of sites (when normally I can cram at least four or five into a day).

Instead of going for quantity, I went for exclusivity—and chose to keep my reservation to the sold-out tour of the Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics (IGPP) Munk Lab at the UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, co-hosted by AIA San Diego. (Fortunately, I could get pretty close to it by taking the new Blue Line trolley extension to UCSD.)

Built in 1963, the post-and-beam style laboratory was the work of San Diego architect Lloyd Ruocco FAIA—who created two elongated structures that cross over each other in a perpendicular formation (in architectural terms, a cross-axial plan), conjoined by a central staircase (and elevator bank that was added later) at their intersection.

Ruocco is widely considered the "Father of San Diego's Post-War Modern Architecture" (the "war," in this case, being WWII)—and is also known for his work on the San Diego Civic Theatre.

An example of organic Modernism, the Munk Lab is considered one of Ruocco's most significant buildings—and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places after an exterior restoration addressed the deterioration of structural redwood and Douglas fir in 2020.

For the tour, we used the east entrance off the campus road known as "Biological Grade" (part of the California Coastal Trail)—and, once inside, faced a long hallway of research offices. Reportedly, this office wing aligns with the sunset on the spring equinox (which we missed by just one day).

Some of the offices appear to be untouched by time, featuring original built-ins, furniture, cabinetry, and other storage.

In the Reading Room, a library of scientific journals and encyclopedias line the walls...

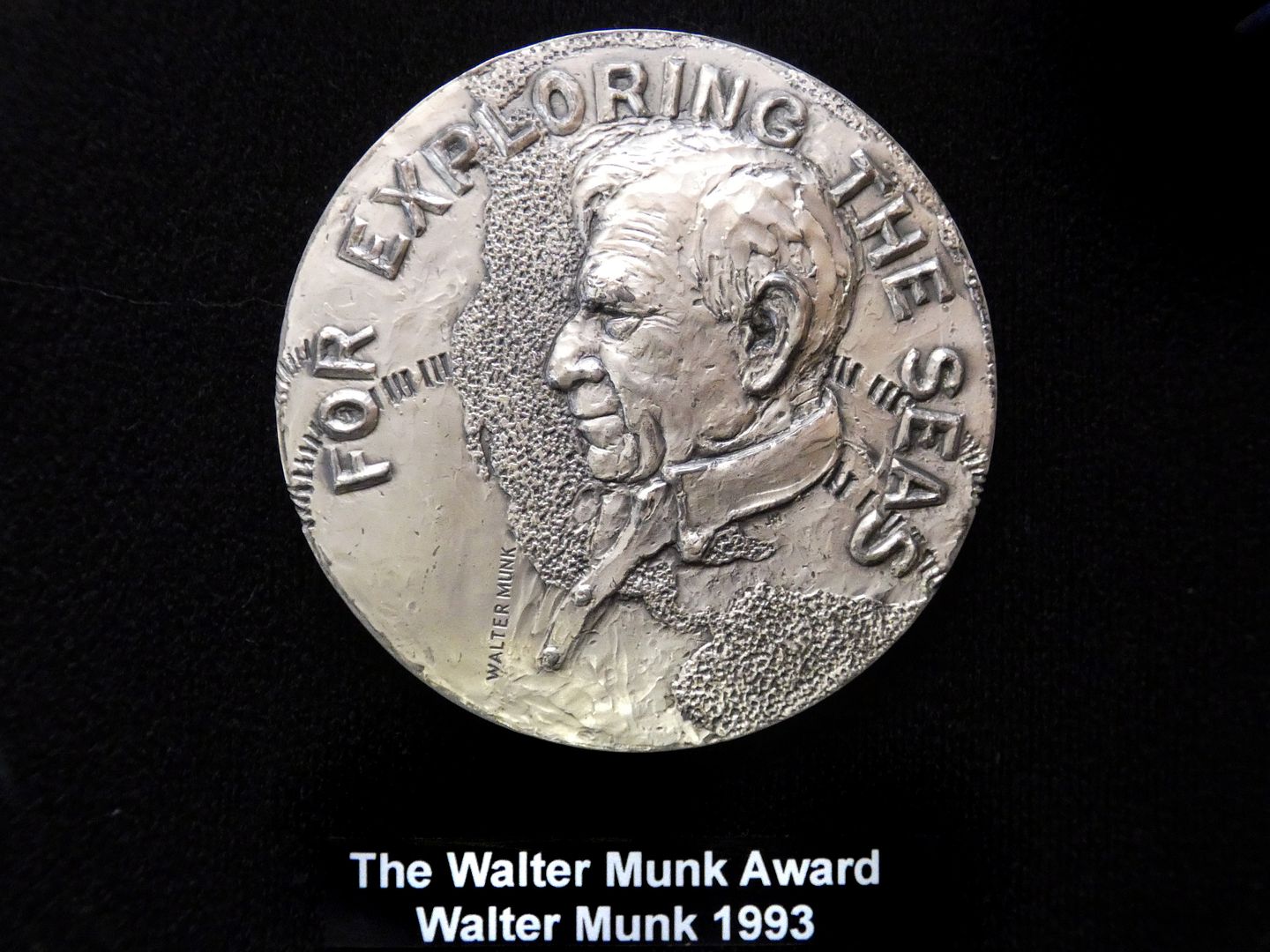

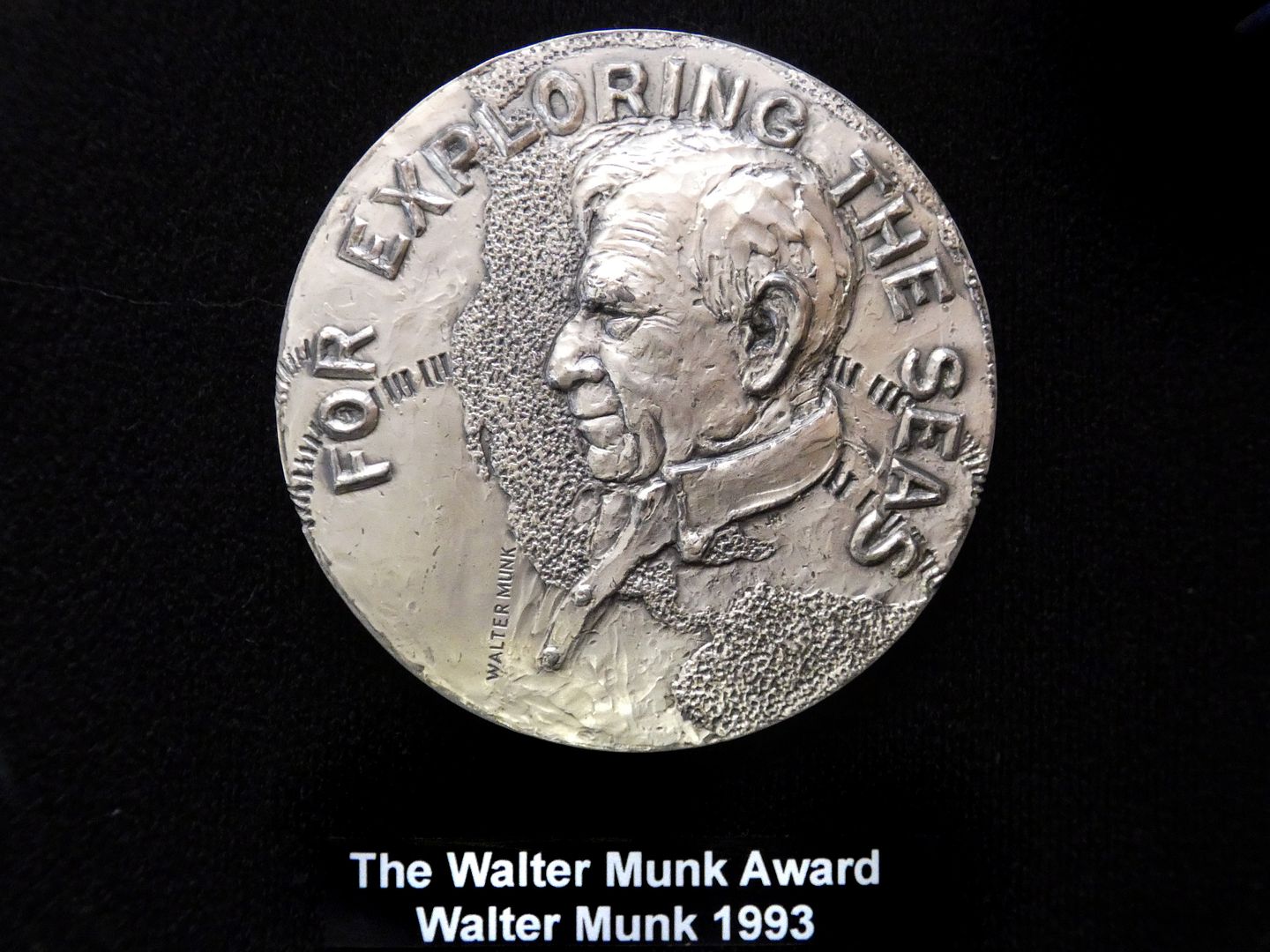

...while a glassed-in display case honors the memory of Walter Munk, the namesake of the Munk Laboratory and widely considered one of the fathers of oceanography as we know it today.

Widely considered the "Einstein of the Ocean," Munk was born in Vienna, Austria but became a famed oceanographer after studying at Caltech and getting hired at Scripps in 1941 while he was still in his early 20s.

During World War II, Munk helped develop methods of predicting sea activity (like the tides) for amphibious battles in the Pacific theater (and even the D-Day landings at Normandy). This same wave prediction technology also revolutionized surfing—and his tide calendars are still used today.

In the 1990s, Munk was testing long-range sound signals in the Southern Indian Ocean—part of his extensive work in ocean acoustics (a.k.a. acoustic oceanography). And he spent the last few years of his career focusing on climate change and monitoring ocean temperatures—even after he'd officially retired, and until his death in 2019 at the age of 101.

Munk was among the university directors who helped establish the IGPP after the war—first conceiving it in 1959 and finally seeing it realized in its new laboratory in 1964. As the institute's first director, he reportedly had a huge input on the design of the laboratory building.

Munk and his second wife Judith chose Ruocco as the project architect—considering the fact that he'd never designed a laboratory before an asset. As Munk said in a 1997 interview, "We thought it should be more like a home than a hall."

In 1993, the IGPP laboratory was renamed in the Munks' honor.

The site-specific laboratory is situated on the Scripps Institute's oceanfront campus—built into a coastal bluff above the ocean, looking out onto the research-only Scripps Pier (which is unfortunately closed to the public).

It has that open floor plan and indoor-outdoor seamlessness that you find on modern-day tech campuses for the same reason: to encourage impromptu meetings and collaborations.

Taking the stairs down one level from the office wing (from floor 3 to floor 2) brings you to the mezzanine above the laboratories...

...where Munk's former office (from 1982, after retiring as director, to 2000) can be found at the end of the hall.

The unfinished redwood paneled walls are adorned with relief maps and other scientific documentation...

...while conference rooms and meeting areas are stacked with books and papers and decidedly non-digital office supplies (and even a photography room for developing film).

The double-height laboratory spaces below each have their own exterior entryways from floor 1.

This is where field crews and equipment are deployed out to the ocean.

Our tour took us into a lab that holds the batteries for their ocean-bottom (OBEM) instruments...

...which measure offshore subduction zones, the impact of water on seismic activity, and the ocean floor (like the SIO seafloor EM receiver, which measures electromagnetic fields).

The Marine EM Lab also deploys Scripps Undersea EM Source Instruments—like SUESI 1 and SUESI 2 (above)—to survey plate tectonics, particularly under the Alaskan peninsula where the the Pacific plate is running into (and under) the North American plate.

During Dr. Munk's tenure, he didn't just join the military effort, working with the U.S. Navy during WWII. He also consulted for multiple U.S. presidents, the Pentagon, and Vice President Al Gore.

But what he loved best was getting out on a boat in the field—and asking questions.

I'm happy to have learned about him on my tour of the Munk Lab—a place that not many people other than oceanographers and geophysicists have gotten to explore.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment