Late ceramicist Beatrice Wood has been called "The Mama of Dada"—a title she scoffed at during her life, even denying that she was an artist herself at all.

But she was part of an avant garde movement—starting when she became lovers with art collector Henri-Pierre Roché and then his best friend Marcel Duchamp, a love triangle that was said to have inspired Roché's novel Jules et Jim (which Truffaut later made into a film).

One of her lasting creations is the nose-thumbing stick figure, Blindman—a reference to The Blind Man Dadaist magazine in New York City, which Wood helped create and publish in 1917, and the illustration that appeared on the poster for the Blindman's Ball masquerade event at New York's Webster Hall. (The sculpture version above was created by a different artist, based on Wood's illustration.)

In 1937, at the age of 40, Wood started selling her wares out of a pottery shop at Crossroads of the World on Sunset in Hollywood to make some money, having taken adult ed classes at Hollywood High. Decades later, she found herself exhibiting at world-class institutions like LACMA in Los Angeles and The Met in New York City.

From 1948 until her death in 1998, she lived and created pottery in Ojai, California—for her final 24 years, at what's become known as the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts.

She felt most at peace in Upper Ojai—under the shadow of the Topa Topa Mountains of Ventura County, her "end of the rainbow."

Part of that might've had to do with her neighbor. She'd intentionally secured property across from Theosophical spiritual leader Jiddu Krishnamurti, whose teachings she'd followed.

She'd even traveled to India—and had gotten into the habit of wearing saris (for both comfort, she once explained, and convenience).

Hers was a rare case of the artwork declining in value after the artist's death—with pieces being sold at a tenth of the going rate when she was alive.

Perhaps because so much of it was sold off following her death, much of the art at the Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts today isn't actually hers...

...but of her former studio assistant Nanci Martinez, sculptor Allison Newsome, and other contemporary ceramicists (many clearly inspired by Wood).

In many ways, Beatrice Wood has become a footnote in contemporary art—despite having been worth millions in the 1980s (and attracting celebrity visitors and collectors). And despite her pieces being part of the permanent collections of the likes of the Smithsonian. (Some may only know her as the real-life inspiration for the character of Rose in James Cameron's Titanic, although Wood herself wasn't on the ill-fated voyage.)

Wood's presence at the center is perhaps most felt in her former studio, where various workshops for the public take place.

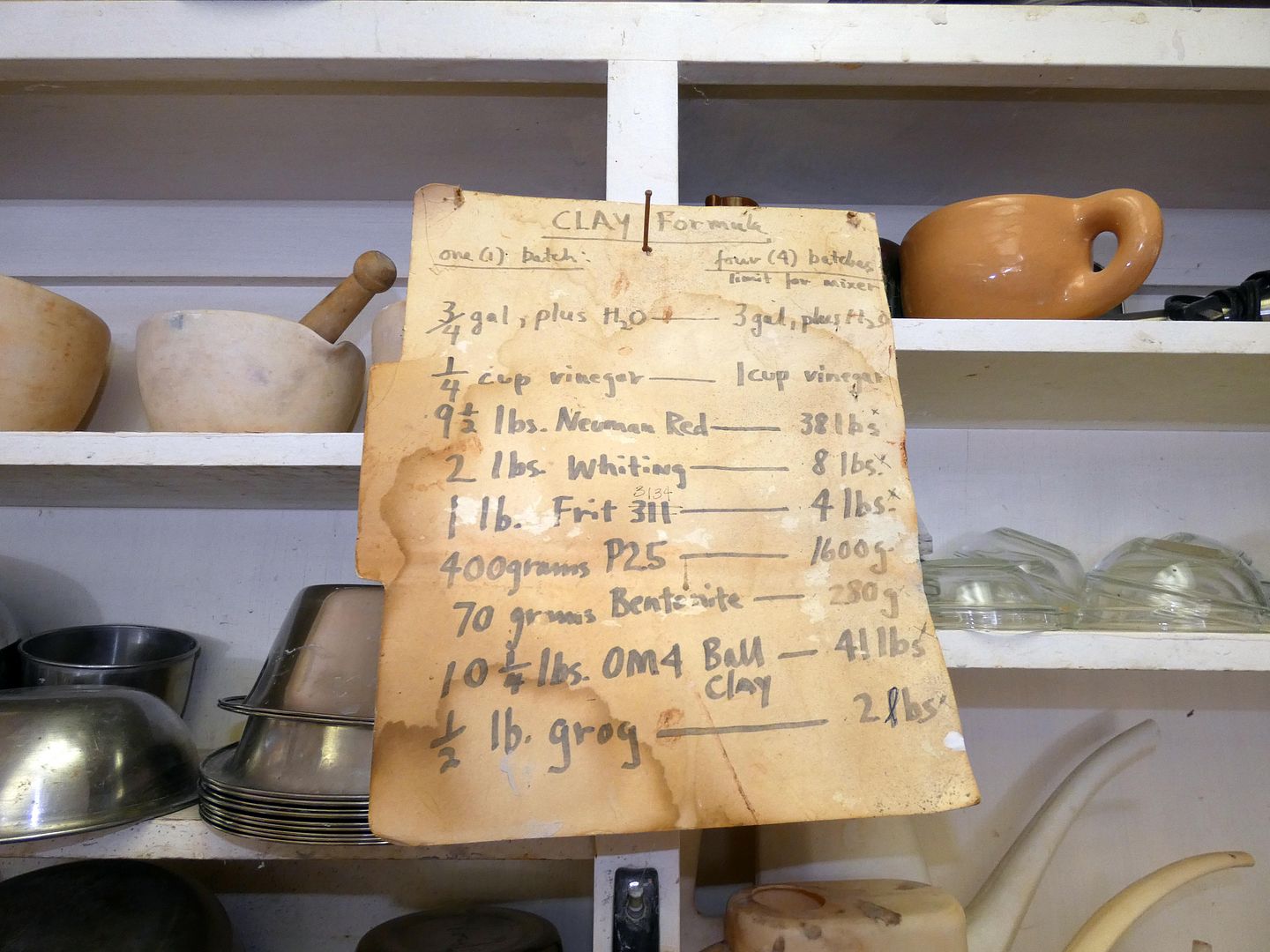

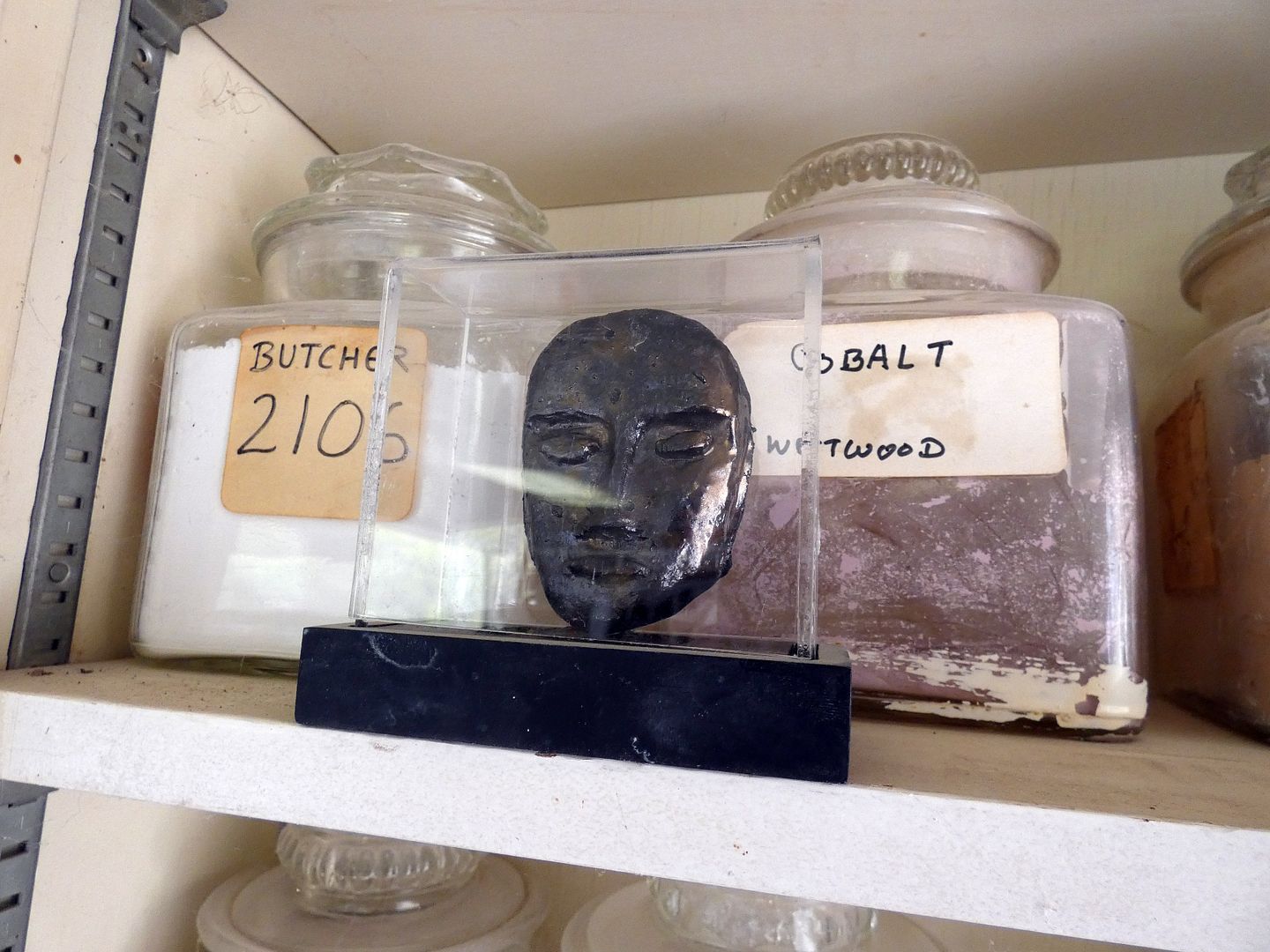

Many of her original materials for creating clays and glazes are still in there...

...although some new additions include ash from the 2017 Thomas Fire, which got dangerously close to the center but was (mostly) kept at bay by crews who used the property as a staging area.

That's not that surprising, given that Wood allowed a portion of her own ashes to be used in a ceramics glaze (the other half being scattered in the nearby mountains).

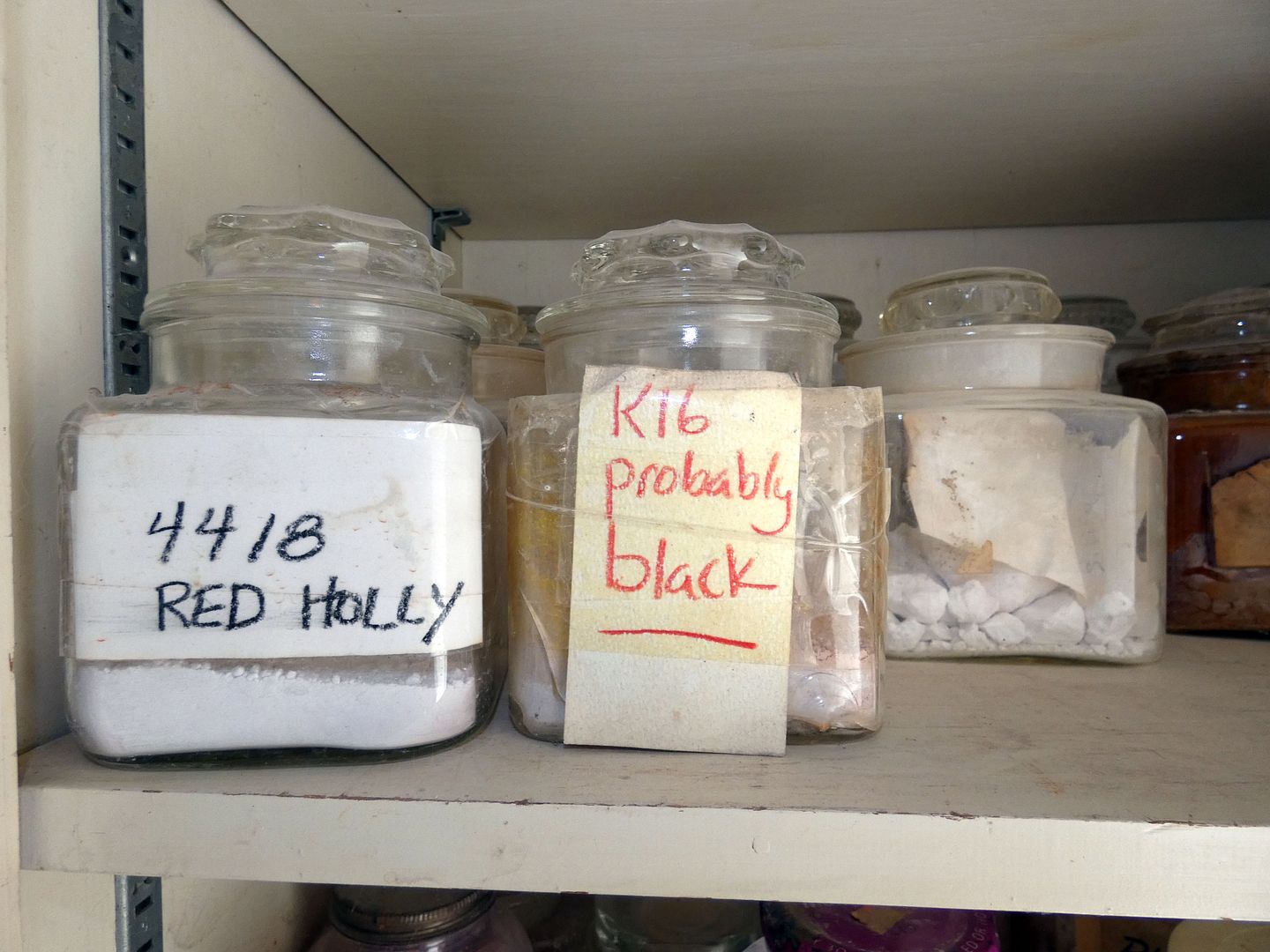

Among the mason stains (above)...

...and glaze chemicals in plastic tubs, lidded jars, and maybe even repurposed milk bottles...

...some somewhat vaguely labeled...

...there are also tiny pieces that appear to show Wood's own technique of luster glaze.

Any works in Wood's former studio that aren't hers at least appear to have been created somewhat in her style.

Reportedly, not much has changed since she stopped working in there herself, a year before her death.

Her unique sets of carving tools, knives, and other pottery equipment remain in their pots. Even the grime on the telephone (which doesn't have a dial tone, but rings sometimes) hasn't been scrubbed off.

After all, why would it be? There's a physical and spiritual patina that Beatrice Wood followers and fans wouldn't want to get rid of. It was palpable even to me, though I'd been as yet uninitiated to Wood's legend and legacy.

After two sexless marriages that followed a string of broken hearts (reportedly, seven men she loved but did not marry), Wood died leaving no children behind—no one to inherit her work, besides the center itself (which is managed by the Happy Valley Foundation, created in 1927 by Annie Besant).

The Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts now operates as a non-profit educational resource, where you can see the last bowls that the potter ever threw on the wheel, frozen in their unglazed state.

There's also the nude, unfinished figure perched on a shell—similar to a style that Wood had become famous for, attaching figurative forms to rocks, crystals, and other natural materials.

Out of the entire compound, the studio was Beatrice Wood's favorite place—and is still the heart and soul of the center.

There, you can see Wood's original plaster molds for some of her folk-art-inspired figures (a.k.a. "Sophisticated Primitives")...

...also just as she left them.

Her kilns are still there—and still used today—including the electric-powered one (above) where she fired up chalices, goblets, footed bowls, and various other types of gilded vessels via reduction firing, a process in which the oxygen supply inside kiln is cut off.

Wood was perhaps more alchemist than potter—as she really hit her stride experimenting with different glaze chemicals and firing approaches to bring metallic elements to the surface, creating an iridescence that came from within rather than being painted on top. Some say she was turning mud into gold.

gas kiln

Beatrice Wood a.k.a. "Beato" found her true calling in midlife—and wrote her first book at the age of 90. She saw her greatest success in her 80s and 90s, long after most people give up on their true passion.

There's hope for the rest of us yet.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment