After visiting all of the other Southern California Spanish missions—including some of the sub-missions (or asistencias)—over the course of my 11 years living out here, I finally got to Mission Santa Barbara (in the Central Coast city of the same name).

Founded in 1786 by the "forgotten friar" Friar Fermín de Lasuén—successor to Junípero Serra—as the 10th of 21 Franciscan missions, it's the only continuously operating mission in the California system. Even after secularization in 1833, the Franciscan friars were allowed to stay—helping this mission avoid the neglect and vandalism that plagued the others that were abandoned.

It became known as the "Queen of the Missions"—a title it has retained, having never fallen into ruins.

Designated a national landmark in 1935, its famous visitors have included Babe Ruth, the Von Trapp family, and Queen Elizabeth.

Situated between the present-day rose garden and the mission church, the great expanse of lawn used to be the site of a vineyard—which was removed when German friars arrived in 1885.

The Germans were also the ones to erect the cross out front in 1913.

Also in front is a relic of daily life at the mission—the lavanderia (a.k.a. "Indian Community Laundry"), which was completed in 1818.

The laundry facility was carved by indigenous prisoners out of native sandstone (although the bear figure is a modern-day replica).

An original carved mountain lion punctuates the other end of it.

Even older is the Moorish fountain, completed in 1808.

The present design of the mission church is based on the Greco-Roman church completed in 1820—the fourth such church constructed on that site. It was actually built over the adobe of the 1794 church, which had been destroyed in the 7.0-magnitude Ventura earthquake of 1812.

The church's Neoclassical style was inspired by the the designs of Roman architect Vitruvius, as found in the book Los Diez Libros de Arquitectura de Marco Vitruvio Polión in the mission library. Much of the stonework was contributed by Mexican master stone mason Juan Antonio Ramírez.

Although the mission church started out with only one tower in 1820, its twin was added in 1830. After collapsing soon thereafter, the second tower had to be rebuilt in 1833.

By that year, the mission had eight bells—but today, that number has grown to 10 bells. Only three of them toll.

In 1925, the 6.8-magnitude Santa Barbara earthquake destroyed the 1820 church. Using mostly original materials (including the salvaged stones), the Franciscans restored it back to its original look (funded by taxpayers) in 1927.

Other restoration efforts, including a major one in 1953, have secured the structural integrity of the church—but haven't significantly changed its overall look.

Inside the chapel, original chandeliers hang from a ceiling adorned with a cloud and lightning bolt motif—perhaps because of its Roman influence, but also perhaps because the mission's namesake, Saint Barbara, is often invoked against thunder and lightning. (The chandeliers still hold candles, but they've also been retrofitted for electricity.)

The original Spanish altar was used in masses conducted not only for the indigenous people the Franciscans were forcibly converting to Catholicism, but also for anyone in the Santa Barbara area (including soldiers as the Presidio). For a while, the only Catholic church in town. Now, it's home to the St. Barbara Parish, under the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.

Catholic iconography abounds, both in paintings and in statuary—like in the scene depicting Mary Magdalene discovering Jesus emerged from his burial tomb.

To take a tour of the mission grounds, you enter the convento or monastery wing—one of the oldest structures on the grounds.

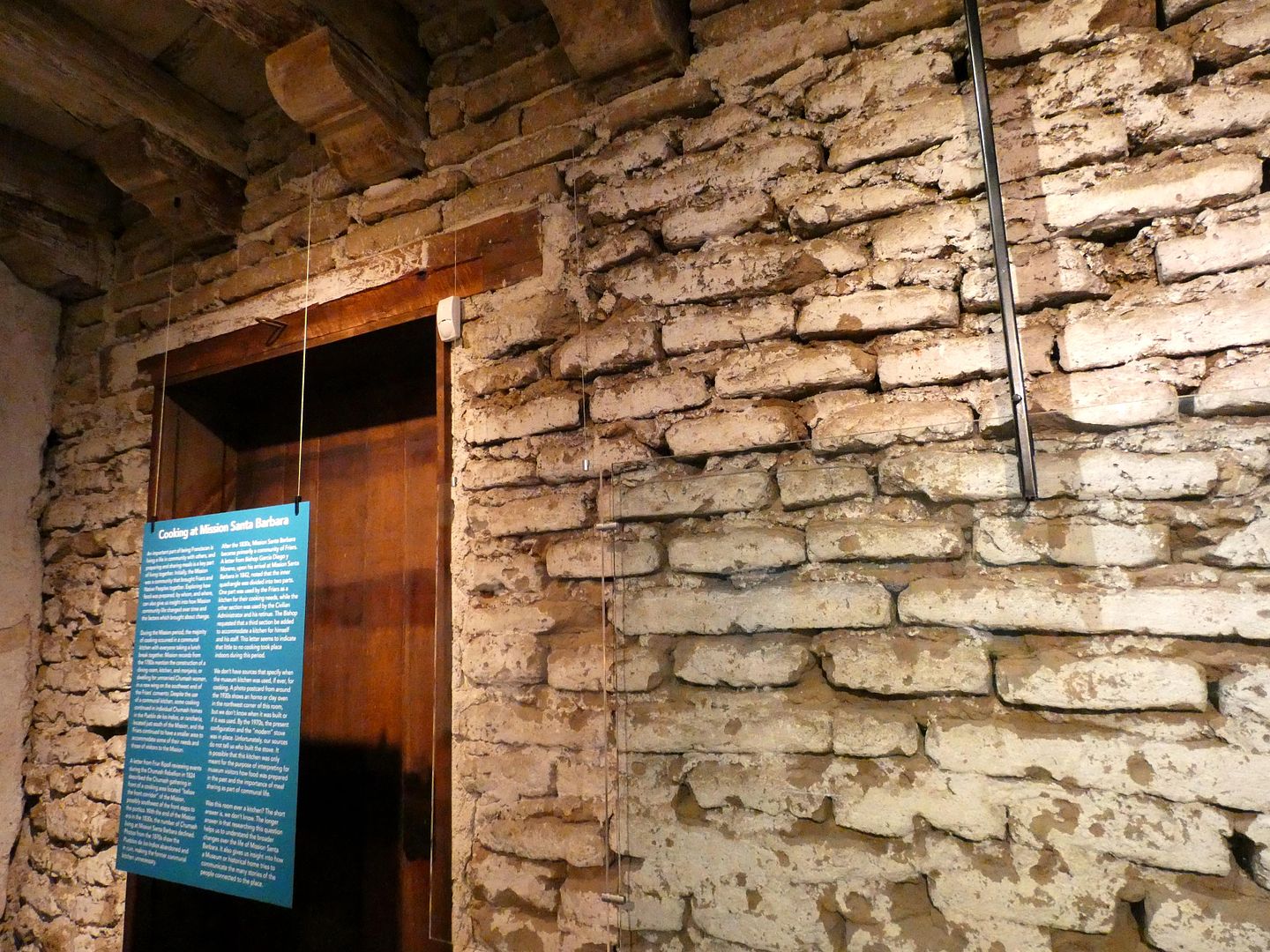

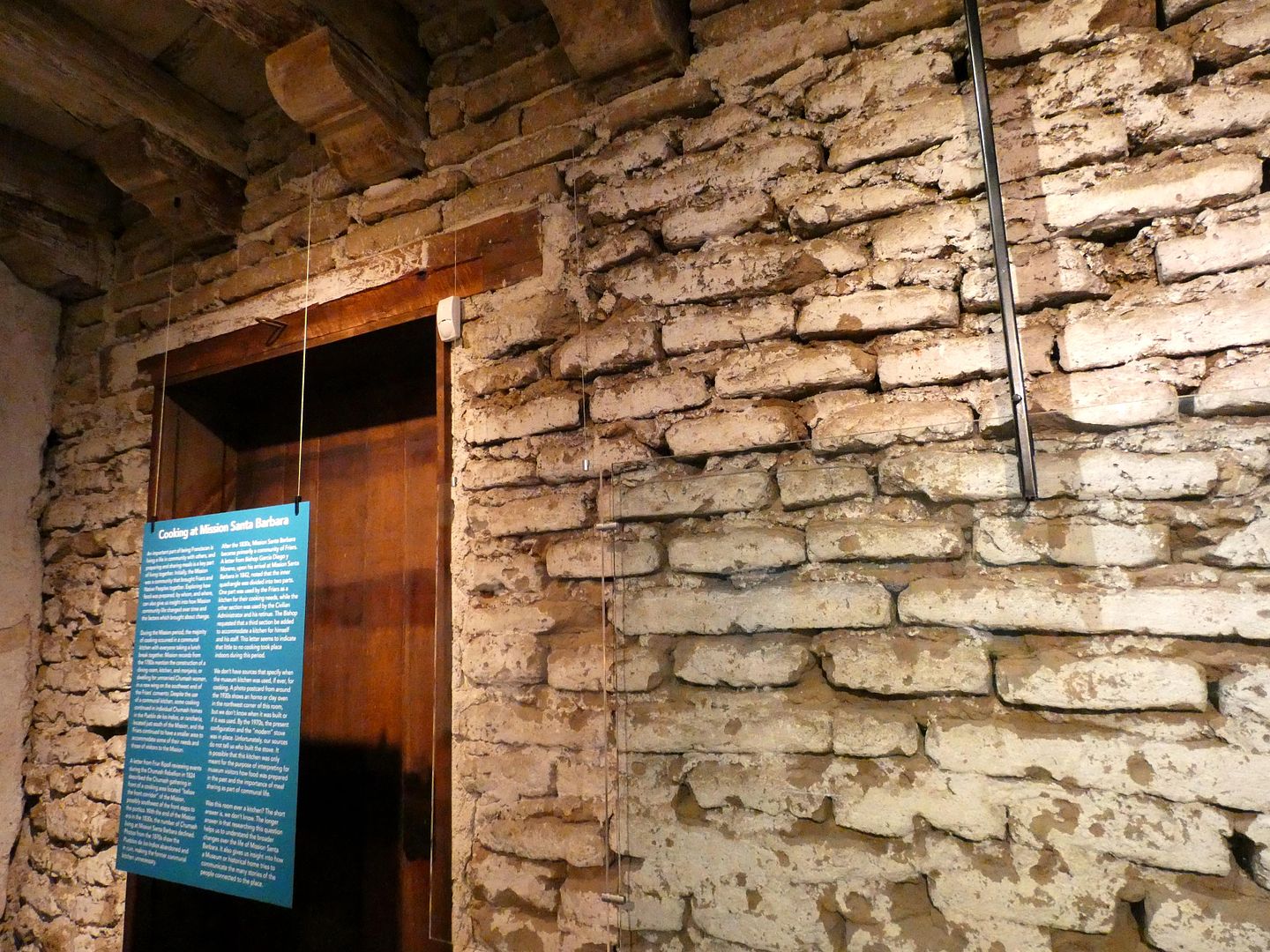

Just beyond the ticket kiosk and gift shop is the museum—the only place at the mission where you can see the historic adobe bricks, circa 1790s. The rest of the convento—beyond the public spaces—is where Franciscan friars lived. Some still live there, even today.

Most of the California missions feature a central courtyard or "inner quadrangle"—a space to gather, complete chores, and create crafts. In 1873, Mission Santa Barbara's "quad" was transformed into a garden with walkways radiating from central fountain (which is actually a Mission-era cistern for water storage).

Now known as the "Sacred garden," the quad surrounded by drainage channels. The mission used to get its water supply from a gravity-fed aqueduct built on the site of the present-day Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, which carried water from what's now called Mission Creek in Mission Canyon.

Some of the other surrounding buildings contain residences, offices, and other spaces not accessible to the public.

Crossing through the mission church from the Sacred Garden gets you to the mission cemetery, established in 1786. Initially, it was where indigenous people (mostly Chumash) who died at the Mission were buried.

Eventually, other community members were laid to rest here, too...

...including non-Catholics.

The cemetery grounds fell into disrepair in the latter half of the 19th century, but they've now been preserved in their historic condition.

In 1893, the former charnel house (a kind of above-ground ossuary) was converted into a mausoleum.

Some of the Mission-era friars were interred in its "old vault," which is also a stop on the mission tour.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the establishment of family mausolea—above-ground structures where relatives could spend all of eternity together.

One of the most famous burials at the Mission Santa Barbara cemetery isn't a friar or early Spanish settler—but Juana Maria, the "lone woman" from San Nicolas Island (a.k.a. The Island of the Blue Dolphins).

And while exiting the cemetery, it's important to take pause at the (replica) skulls and crossbones—an early Catholic symbol for the transition between life and death. At Santa Barbara Mission, as it would at any Spanish cemetery (campo santo), it marks where you're leaving the place of death and reentering the land of the living.

Related Posts:

Helped me with my Santa Barbara project

ReplyDelete