Earlier this month, Pescadero, California was the site of a sesquicentennial celebration for Pigeon Point Lighthouse—built in 1871 (one of eight built that year that are still standing) but first lit at sunset on November 15, 1872.

Pigeon Point gets its name from the wreck of a commercial clipper ship called the Carrier Pigeon, which got lost in the fog on its maiden voyage from Boston to San Francisco in 1853—surviving the passage around Cape Horn, an area notorious for its shipwrecks.

Initially known as "Carrier Pigeon Point," the nickname for the area got shortened over time to just "Pigeon Point"—and its prime visibility combined with the treacherous waters below made it a great place for a 115-foot-tall lighthouse tower to help guide mariners. Along with the Point Arena Lighthouse in Mendocino County, it's tied as the tallest lighthouse on the West Coast.

Originally built out of 500,000 locally-made bricks and double-walled to protect the interior from the elements, Pigeon Point Lighthouse has been designated a California Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, California State Historic Landmark, and a federal landmark listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

However, the interior hasn't been open to the public since its stability was compromised when 300-pound chunks of its metal bracing (a.k.a. the iron belt course) fell off in 2001. That was because of because of rust and corrosion in the cast iron and masonry—and not because of damage from the two fires and two earthquakes (1906 and 1989) it survived.

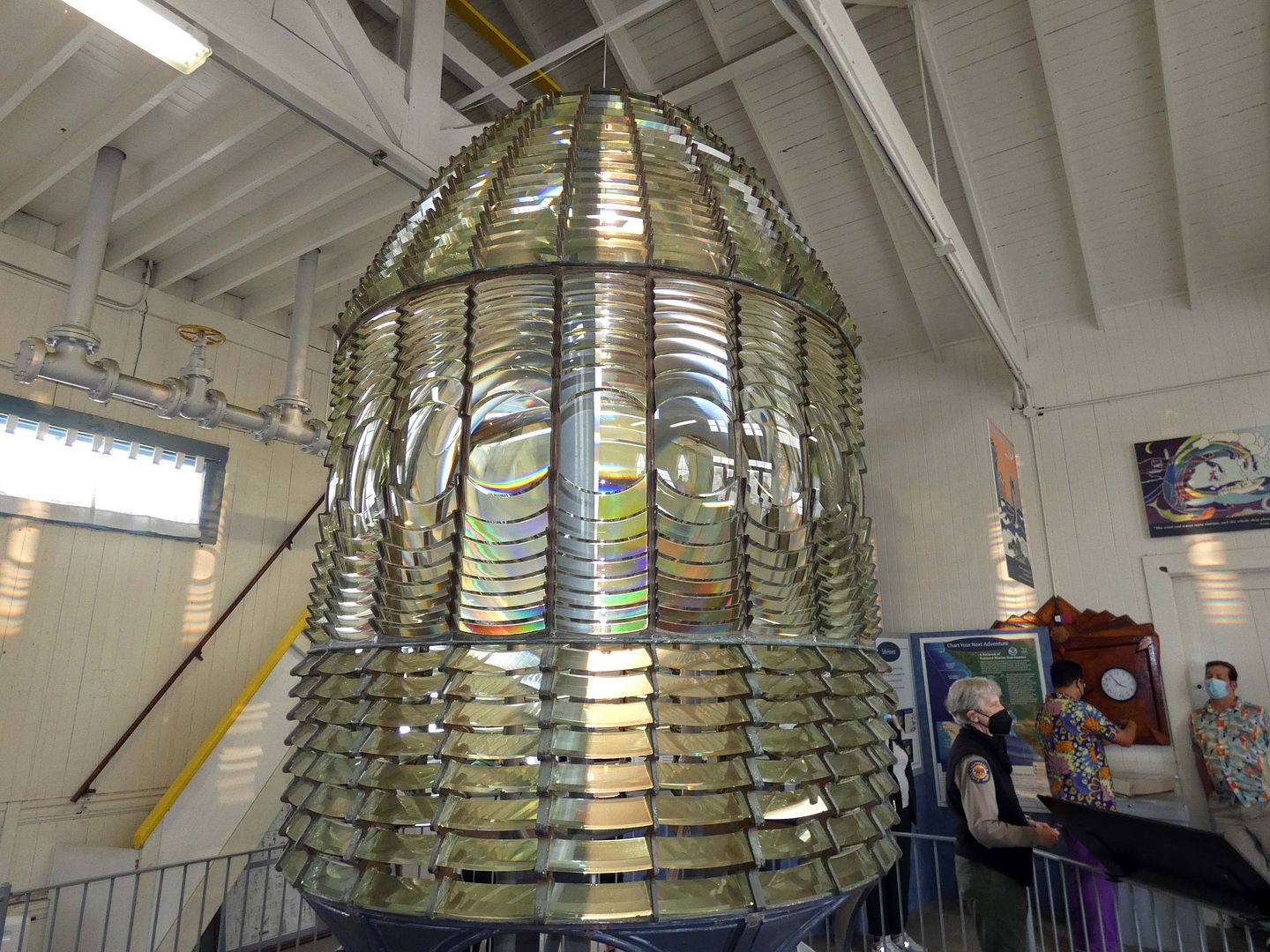

The copper roof needs repairing, too—and, in anticipation of a major upcoming renovation to help the lighthouse regain and retain its original beauty and character, the Fresnel lens has been temporarily relocated from the lantern room to the Fog Signal Building next door.

Fortunately, we got the rare chance to enter Pigeon Point Lighthouse as part of Doors Open California, accompanied by California State Parks docents and volunteers...

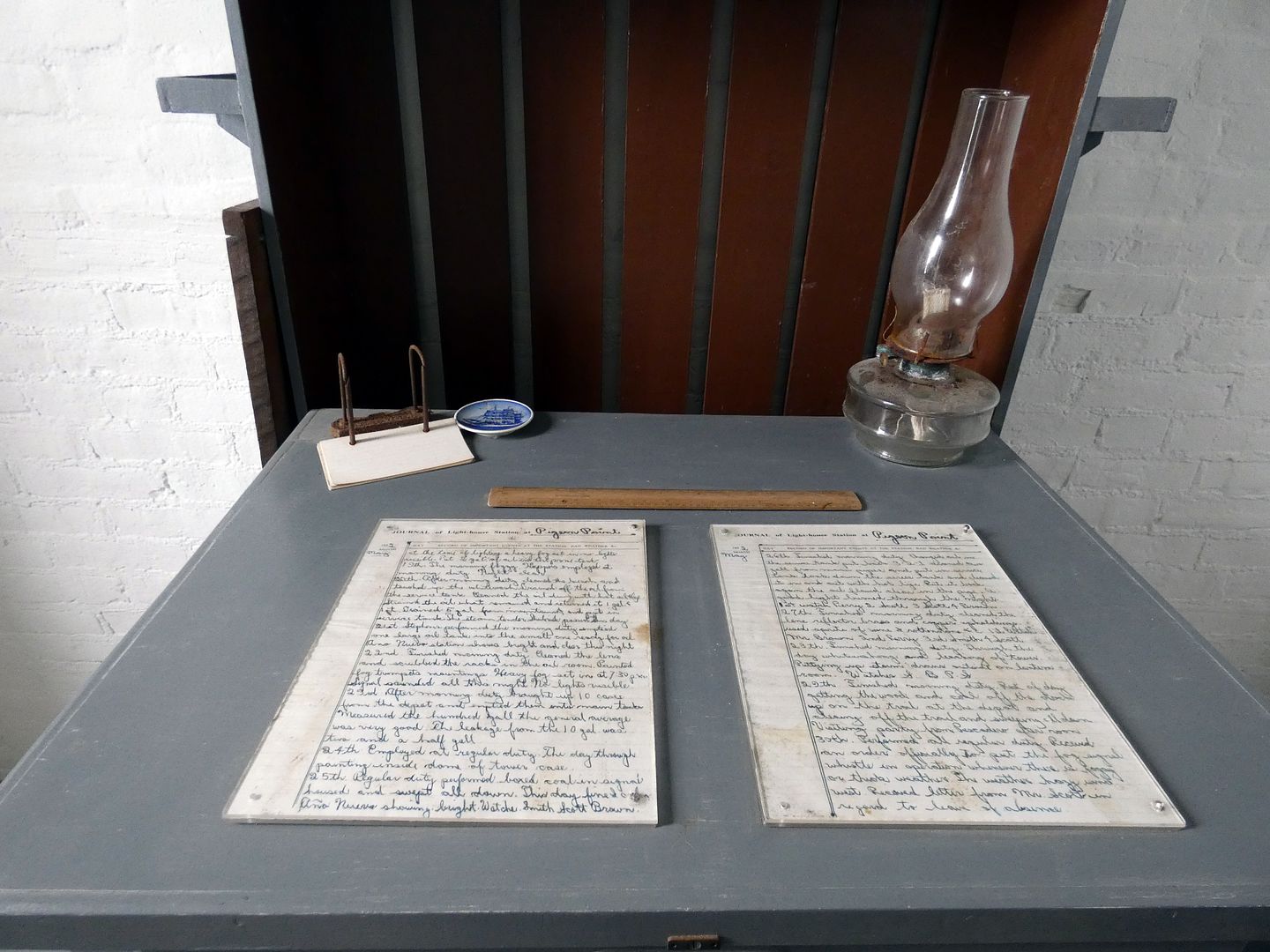

...who took us up to the service room...

...where the lighthouse keepers worked during the day to maintain accounts (they had to be able to read and write), swept the floor, polished the brass, and kept a fresh coat of paint inside and out.

They also served as onsite security for the lighthouse. Past keepers were strong-armed by rumrunners at gunpoint and even saved seamen from a wrecked fishing vessel.

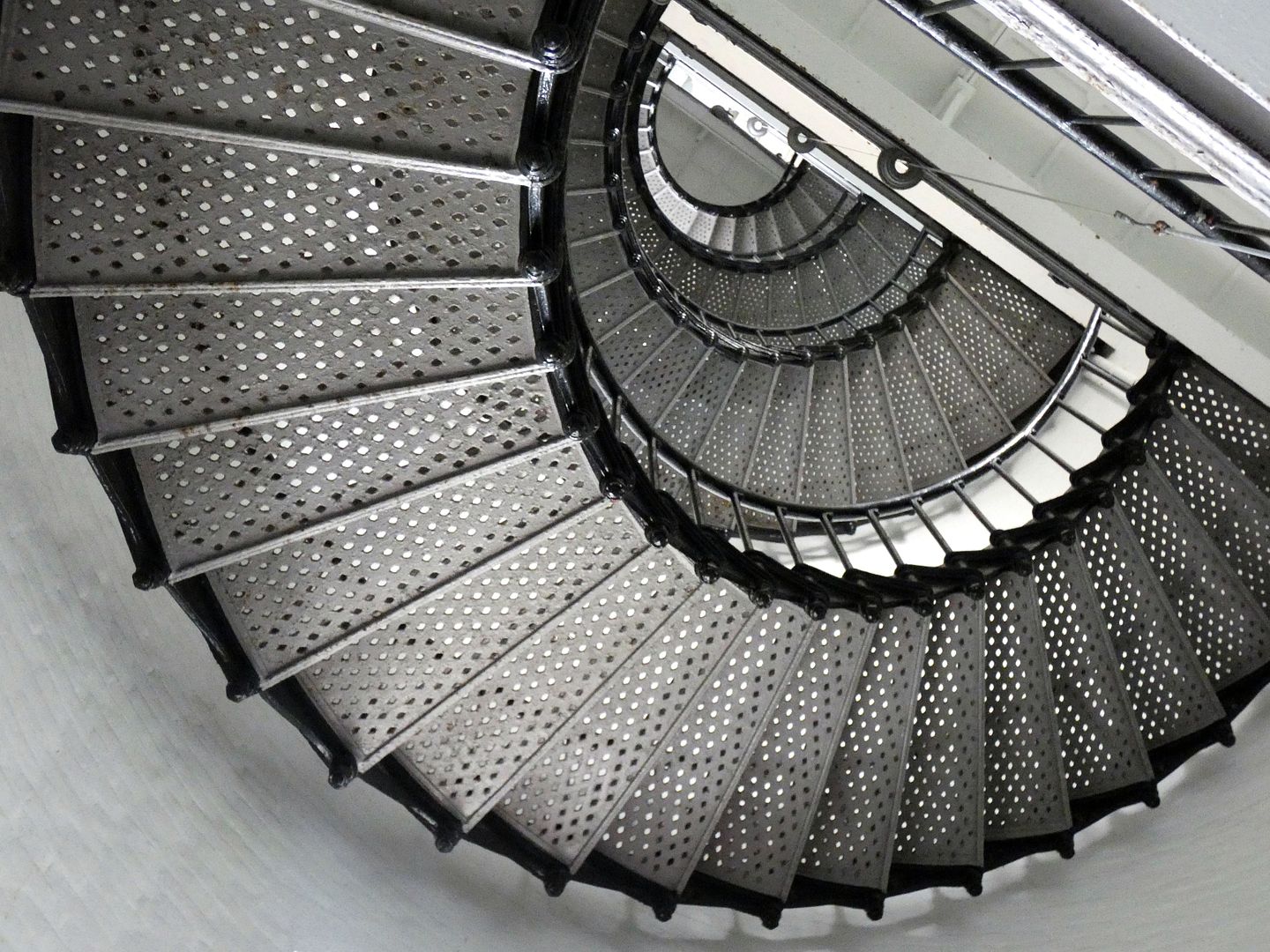

Although we weren't allowed to ascend as high as the upper tower or the lantern room, we got to look up into the lower tower.

The story goes that the builders couldn't figure out how to assemble the 136 iron steps at first—until they contacted where they'd been forged in San Francisco and found out that they were all numbered to demonstrate how they fit together.

Although the light itself is now automated, Pigeon Point Lighthouse once needed three to four keepers (a head keeper and his assistants)—who, at night, initially hand-wound the clockwork mechanism of the lens (which slowly rotates it so mariners see a white flash every 10 seconds). The lens used to sit on "chariot wheels" and rotate by a mechanism similar to a grandfather clock. Time was "kept" with the help of an 80-pound weight, suspended by a cable, which descended 25 feet in four hours and had to be cranked up again.

Those who kept the flame alight on the wick lamps of the lantern—using lard oil from 1872 to the 1880s and kerosene from the 1880s to the 1920s—were known as "wickies."

Aside from the special weekend that we visited, the grounds are always open to the public—as is the Fog Signal Building (not the original, but a replacement circa 1899), where the relocated lens is now housed.

The 10-foot-tall, 2,000-pound First-Order Fresnel lens is comprised of 1,008 delicate glass elements—24 bullseye lenses and 984 prisms—which cast 24 beams of light that could be seen as far as 24 miles offshore.

It had to be carried down piece by piece from the top of the lighthouse tower when they relocated it.

It was electrified in the 1920s. Starting in the 1970s, it was automated with an exterior beacon. Today, mariners are guided by an 80-watt LED beacon, which is visible for up to 14 miles.

It's worth a trip to the back of the Fog Signal Building to take a gander at the now-silent fog horn trumpets—two diaphone horns used from 1935 to the 1960s. They reportedly sounded like "Bee-Ohh" and could be heard as far as 5 miles offshore. The first fog signal, from 1871 to 1911, had been a whistle that sounded like "A cow in distress," powered by steam pressure created from burning wood. From 1911 to 1935, it had been an air siren—compressed air amplified by a horn, powered by a gas engine. In the 1960s, the twin trumpets were replaced by a single-note diaphragm horn, used until 1976.

From back there, you can peer out over the 50-foot rocky bluff covered in flowering ice plant and see the treacherous waters still used by a local crab-fishing fleet and personal fishing boats.

Northern elephant seals poke their noses out from between submerged rocks, swirling currents, back eddies, and a thick haze. When we complained a little that it was raining, the park staff told us, "It's always kind of like this at some point during the day."

California State Parks officially acquired the property from the Coast Guard in 2005 and operates it as a park, but there's another way the public can enjoy the property: by staying in the bungalows that were built later on and are now used as part of a hostel operation.

Watch the guided video tour and click through the 3D tour in the embedded player above.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment