Riverside, California has got plenty of historic architecture—from Victorian to Mid-Century Modern—but one of its most intriguing historic homes defies definition when it comes to architectural style.

And what's more, it's located in the most unexpected of places: in the parking lot of the Courtyard by Marriott Riverside UCR/Moreno Valley Area hotel on University Avenue (a.k.a. Old Highway 395), in a former orange grove.

The Weber House was named after and designed by Peter J. Weber, who worked as chief designer for architect G. Stanley Wilson's firm. Weber had helped design the Mission Inn's International Rotunda, where the firm eventually moved its office—but his family home and office was his magnum opus, built between 1932 and 1938.

The brick-clad house, a Riverside city and national landmark, exhibits an unusual blend of Moorish, Craftsman, and Art Deco architectural styles...

...brought to life through many recycled and reclaimed materials (including a circa 1935 solar-powered rooftop water heater, which was constructed out of car windshields, though it's since been removed and was recently repaired and put back into place).

Nearly all the building materials in the house were salvaged—including the bricks, which came from the demolished Riverside High School, having been damaged in the 1933 Long Beach earthquake. Salvaging and reusing was just a necessity during the Great Depression, when pretty much everyone was too poor for new materials.

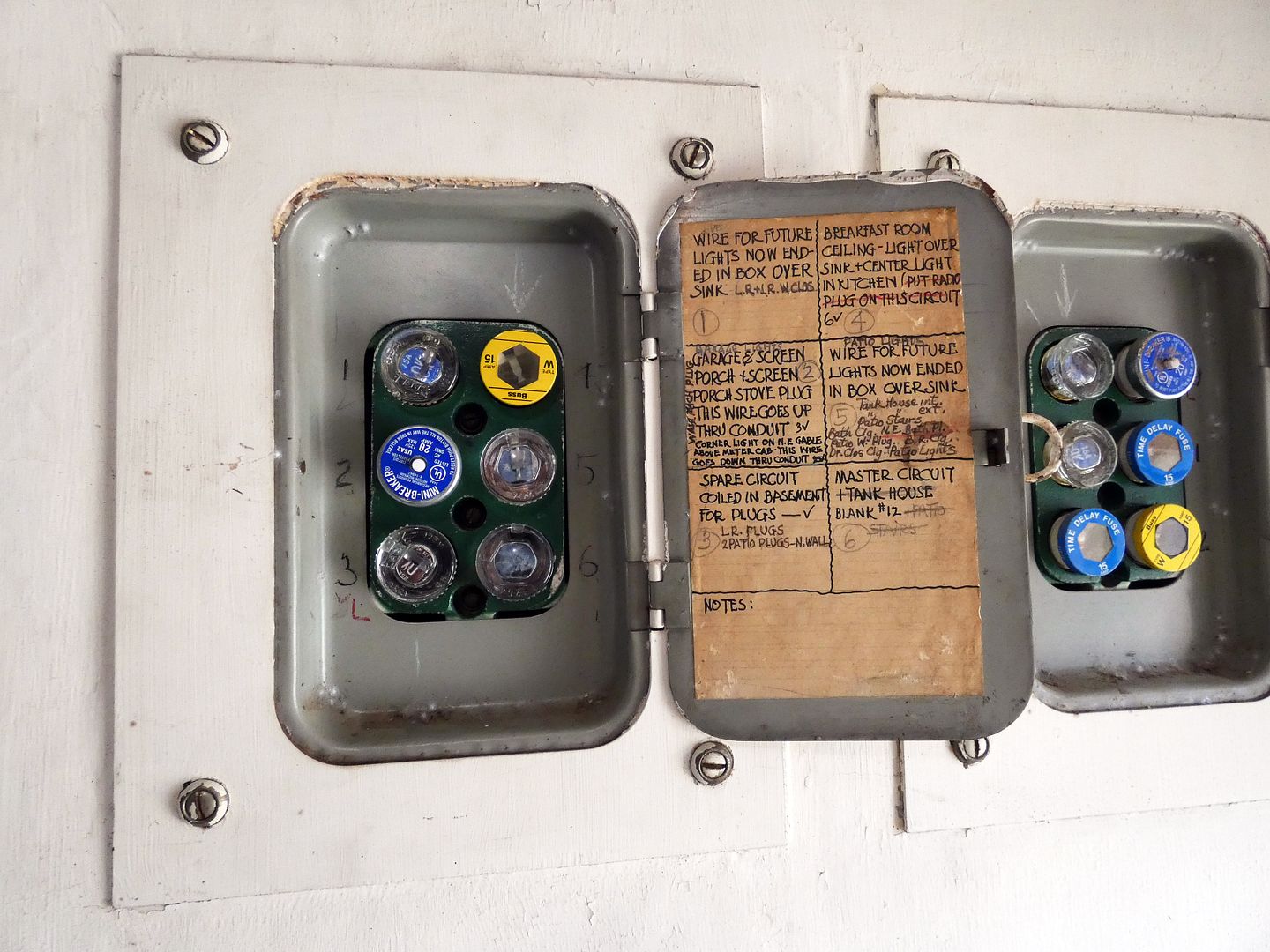

The current front entrance of the Weber House, which is open by appointment as a historic house museum run by Old Riverside Foundation, was once the back door. It takes you into the former wash house and laundry room, where you'll find an old fuse box with original handwritten descriptions.

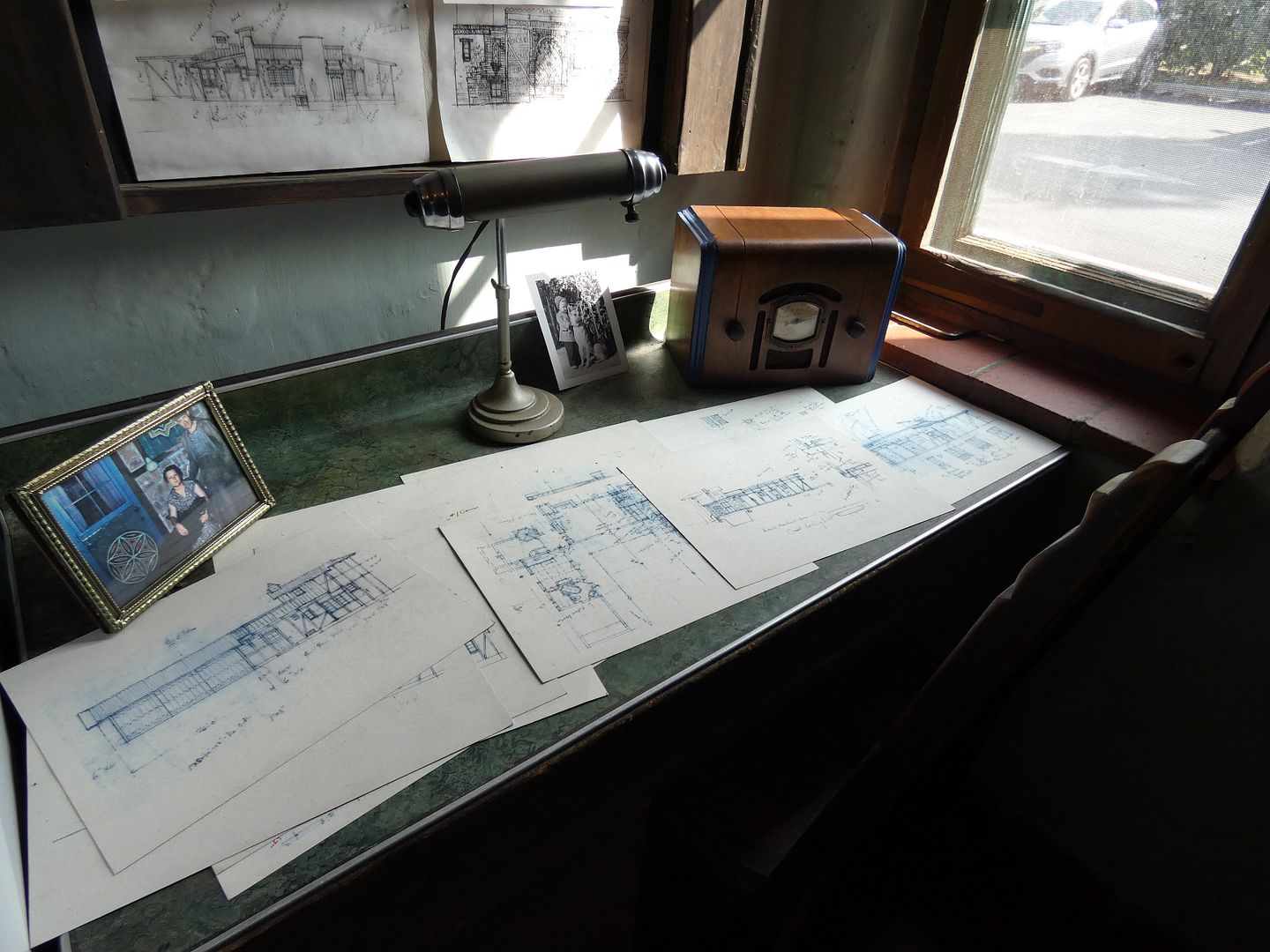

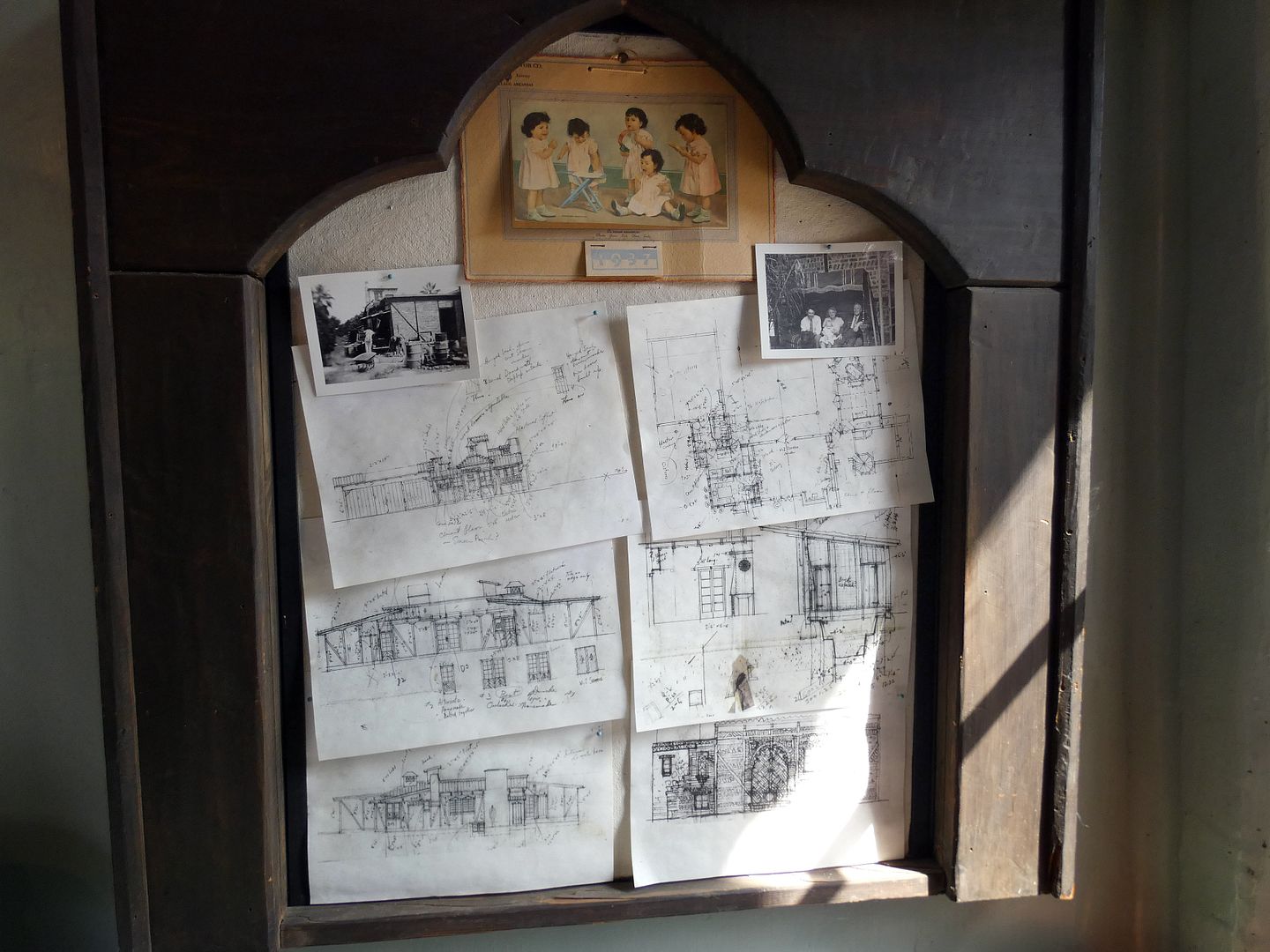

From there, you proceed past Weber's old drafting desk...

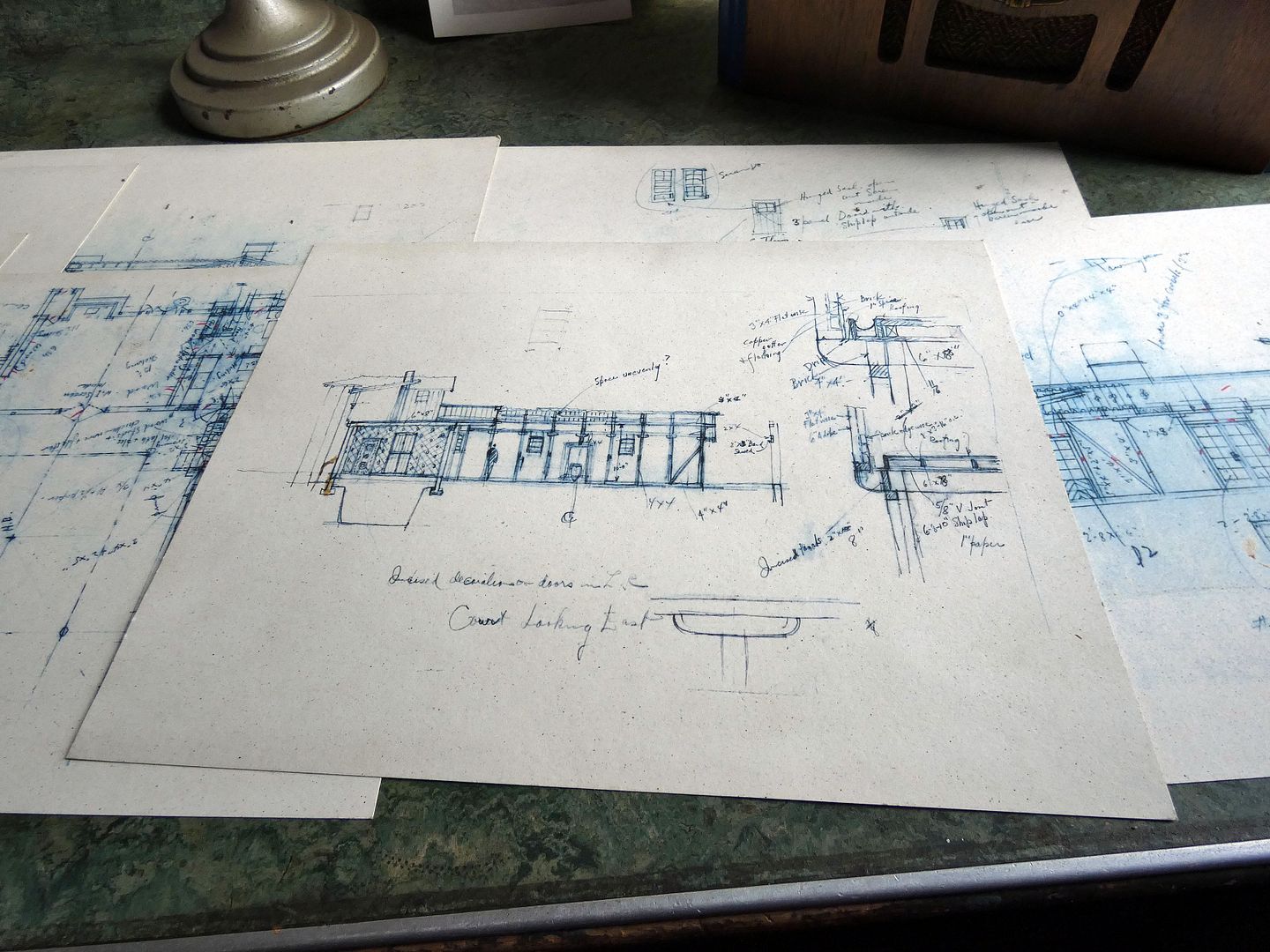

...where architectural drawings are still scattered about...

...showing Weber's original vision for the home.

In the adjacent kitchen, cabinet doors feature reclaimed hardware and decorative nail heads—like all doors in the Weber House.

All the carvings were done by Weber himself, with a hammer and chisel.

At the kitchen sink, Gladding McBean tiles are shaped to allow any water to drain directly into the sink and colored in Weber's chosen palette of blue (some combination of Cobalt Blue, New Blue, and French Blue) and Emerald Green.

In the dining/breakfast room, a hand-painted ceiling (whose pattern matches the floor below) looms over a wood-burning stove that was later converted to oil...

...and whose sheetmetal encasement was designed and hand-forged by Weber.

A carving above reads, "Welcome is the best cheer."

The living room's carved walls bear Moorish designs and hide compartments of storage behind panels of wood that was oiled with used motor oil (which was in abundant supply at the time, especially on a citrus ranch, though not exactly fire-safe).

There are also renderings of the Weber House showing its current footprint overlaid with the original plans to build extra bedrooms and a tower.

Oversized double doors let in plenty of light (and the illusion of space under the pine-plank ceiling)...

...while fixtures lend a sense of intimacy on the other, darker side of the room, by the fireplace.

The outdoor courtyard serves not only an extension of the family room...

...but also as something of an architectural showcase...

...to demonstrate to clients of G. Stanley Wilson's firm what kinds of materials and patterns might be available for their projects.

Many of the same patterns found inside continue to the outside...

...in the exterior of the U-shaped building that surrounds the courtyard (and in the shadow of the Courtyard by Marriott).

A dizzying display of patterns abound, from chevrons and zig-zags to 12-pointed stars.

The bedroom wing can be accessed through a mosaic tile-covered bathroom (actually the last room in the house to be built)...

...whose walls and floor are covered in Gladding McBean "factory seconds" of tile fragments that Weber bought for $5 per barrel and then sorted by color.

Weber also fastidiously tracked his weight in white pencil on the window frame, as a parent might document a child's height in a doorway.

Above the bathroom, there's a hand-painted, stepped pyramid-style ceiling...

...and below, an inviting sunken tub.

There's only one bedroom that was completed in the house—despite plans for more and despite the fact that Weber and his wife Clara lived there with their son, Peter N. Weber ("Pete"), who was born in 1938 (and died in 2020).

Peter, Clara, and Pete actually slept on a parapet on the roof all year long, accessible via a staircase off the courtyard—which Pete reported got pretty loud during WWII with the big planes flying out from March Air Field and all the air raid sirens going off. During that time, this was where Grandma moved in and stayed (hopefully shielded somewhat from all that noise).

Weber's primary influence in the design of his family home was from a trip he and Clara had taken to North Africa—but you can find plenty of other architectural elements, too, including Tudor.

To see it for yourself, book a tour with Old Riverside Foundation or attend one of their regularly-held salvage sales. (True to the tradition of the home, there are many salvaged items stored in the basement of Weber House—from windows and doors to hardware, lighting fixtures, and even appliances.)

For a personal tour given by Pete Weber of his boyhood home, watch the video below:

Adapted somewhat from my article "5 Can't-Miss Riverside Art and Culture Destinations" on KCET.org.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment