For my first trip back to NYC in five years, staying with a friend wasn't really an option—so I took the opportunity to stay in the weirdest and most historic hotel I could think of.

It's now a boutique hotel called The Jane, located in the westernmost environs of Greenwich Village, just steps from the East Bank of the Hudson River.

I remember its big reopening in 2008, with much fanfare. It then became a huge nightlife destination, though I don't recall ever drinking or dancing in its Victorian-style "ballroom."

But my return visit would be very different—sleeping in a hotel room I vaguely knew had been built for sailors and that one of the Titanic survivors might've occupied in 1912.

Of course, it turned out I was actually going in a little blind—because there was so much I didn't know about The Jane.

You see, it began its life at 507 West Street in 1908 as the American Seamans Friend Society Institute Building—built by the non-sectarian although decidedly religious (and even evangelical) Seamens Institute.

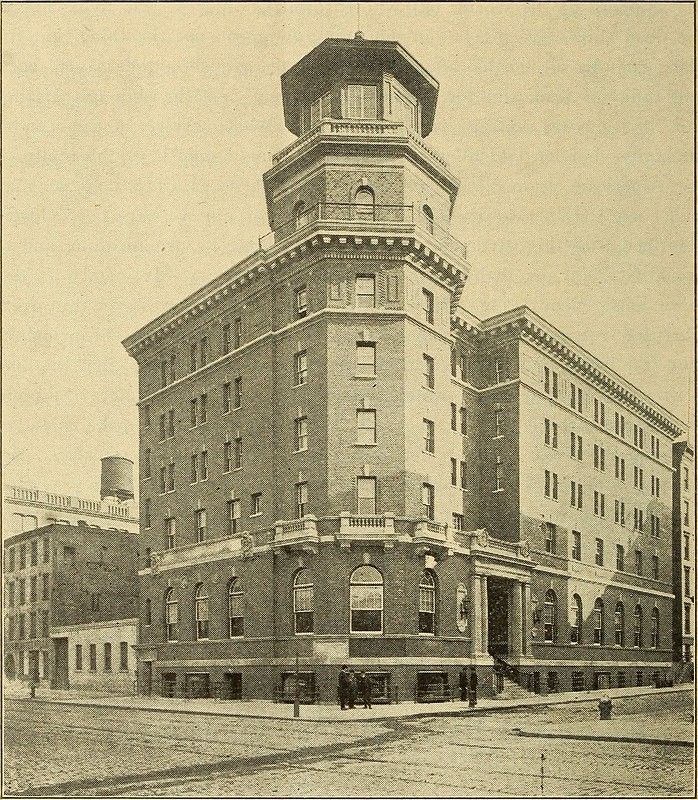

circa 1909 (The Acts of the Apostles of the Sea, page 69) via Internet Archive Book Images (Public Domain)

According to the 1909 book The Acts of the Apostles of the Sea, the institute—whose president at the time was the Reverend Dr. Charles A. Stoddard—stood as "the largest distributor of the Word of God on the waters." Not only that, the book continues, the society "aided shipwrecked and destitute seamen of every race and nation, fed the hungry, clothed the naked, [and] buried the dead."

circa July 2022 (Google Street View)

According to a 1907 article in The Brooklyn Times, it would offer to the half-million sailors who passed through the Port of New York annually "a place where they may find friends and comfort and some of the privileges enjoyed by their more fortunate brothers ashore"—including a bath, a chapel, and even a bowling alley. A 2001 article in The New York Times added that it also offered "a good place to go instead of a brothel."

In 1912, the Seamen's Institute would step in to help the surviving crewmembers of the Titanic—officially designated as "destitute British seamen," who'd been "plucked from the wreck," according to The New York Times.

From what I could see, the exterior of the former Sailors’ Home and Institute looks nearly the same as it did when Titanic survivors were photographed in front of the building. But unfortunately, The Jane Hotel is undergoing yet another renovation after changing ownership in 2022—which meant that scaffolding obscured many of the details during my visit.

The Georgian-style building was the work of architect William Alciphron Boring, who'd also designed the Ellis Island Immigration Station (1897-1901) with his frequent collaborator, Edward Lippincott Tilton.

In 1944, the YMCA took over the building (and removed the beacon at the top of the octagonal tower in 1946).

Sailors once paid 25 cents per night to stay here—but in the 1980s, single guests were being charged $14.57 nightly (with a three-night minimum) to stay at what had become the Hotel Riverview at 113 Jane Street. (The price went up to $39/night by 2001, though at some point it had earned the reputation for being a flophouse, in a complete turnaround from its initial moral fortitude.)

I thought it was an absolute steal for me to pay $103/night in 2023—just a little more than the $99/night it charged in 2009. Maybe it was so cheap because of the construction happening—and the fact that the restaurant, Jane Ballroom nightclub, and rooftop bar were all closed during the renovation.

It felt like The Jane had almost been returned to some pre-2008 state, when celebrities didn't gather there and the only visitors were those who wanted a cheap, safe place to crash for the night with a door that locked.

It was a ghost of a hotel with perhaps more than a few ghosts as its occupants.

I was delighted to receive five-star service at the front desk and the bell desk.

And the lobby features a mish-mash of decor, perhaps Victorian, that reads like a cabinet of curiosities.

Upstairs is a bit more nautical—with porthole windows in the hallway doors leading to the stairwells (although there is an elevator).

Long, narrow hallways are lined with single-occupancy and double-occupancy rooms filled with bunks, some stacked.

A couple of the doors along the way to my hotel room sported old paint jobs, vintage doorknobs and doorpulls, and keyholes instead of electronic key fob readers. Turns out some of the SRO tenants got grandfathered in and were allowed to stay (although others were evicted in the transition to becoming The Jane Hotel).

I was assigned room 349—actually not far from the elevator, but because of construction, a left turn and then a right, a right, and a right to get there.

The room itself was only slightly wider than my full armspan.

The wood-paneled sleeping quarters reminded me of a train roomette, with a smaller-than-twin-sized mattress that wasn't much longer than my 5'4" stature. (The berth was still more comfortable than spending a night on the Battleship IOWA.)

Electrical power required a metal post to be inserted in a slot—which seemed olde tyme at the time but I think may be a more modern amendment for saving energy.

And the stumbling block for most people, I think, is the communal bathroom: two toilet stalls and two shower stalls, both unisex, shared by the entire floor. Fortunately, it was very clean and surprisingly private.

I'd like to go back when the restaurant reopens to see what they do with it—and hopefully get a better look at the outside of the building, which I don't really remember from the one time we had dinner there in 2010.

I also can't recall what I ate back then—but a menu in the New York Public Library collection shows that in 1914, you could get a double porterhouse steak with onions for $1.00. You could also get an oyster omelette for 25 cents, roast mutton for 20 cents, or stewed prunes for 5 cents.

For more historic and contemporary photos before the current renovation, visit this article by the New York Post.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment