I've been chasing monarch butterflies in California for a few years now. But I've largely failed.

I've never seen the hoards of migrators that used to fill the skies—and trees—of Central and Southern California on their way down to Mexico. I've only heard the stories.

Honestly, by the time I started really looking for them, their population had dipped so much, I'd be happy to see just a single monarch.

But I've kept trying. And I felt a little optimistic this time around, hearing that the declining monarch numbers might actually have begun to rebound a bit.

This past weekend, I was driving to Paso Robles when I decided to get off the 101 Freeway and detour to the Monarch Butterfly Grove at Pismo State Beach along California's Central Coast.

I wondered why it was hard to find parking in the small lot or along the side of the road—and then when I entered the grove, I started noticing fluttering wings flying through the air.

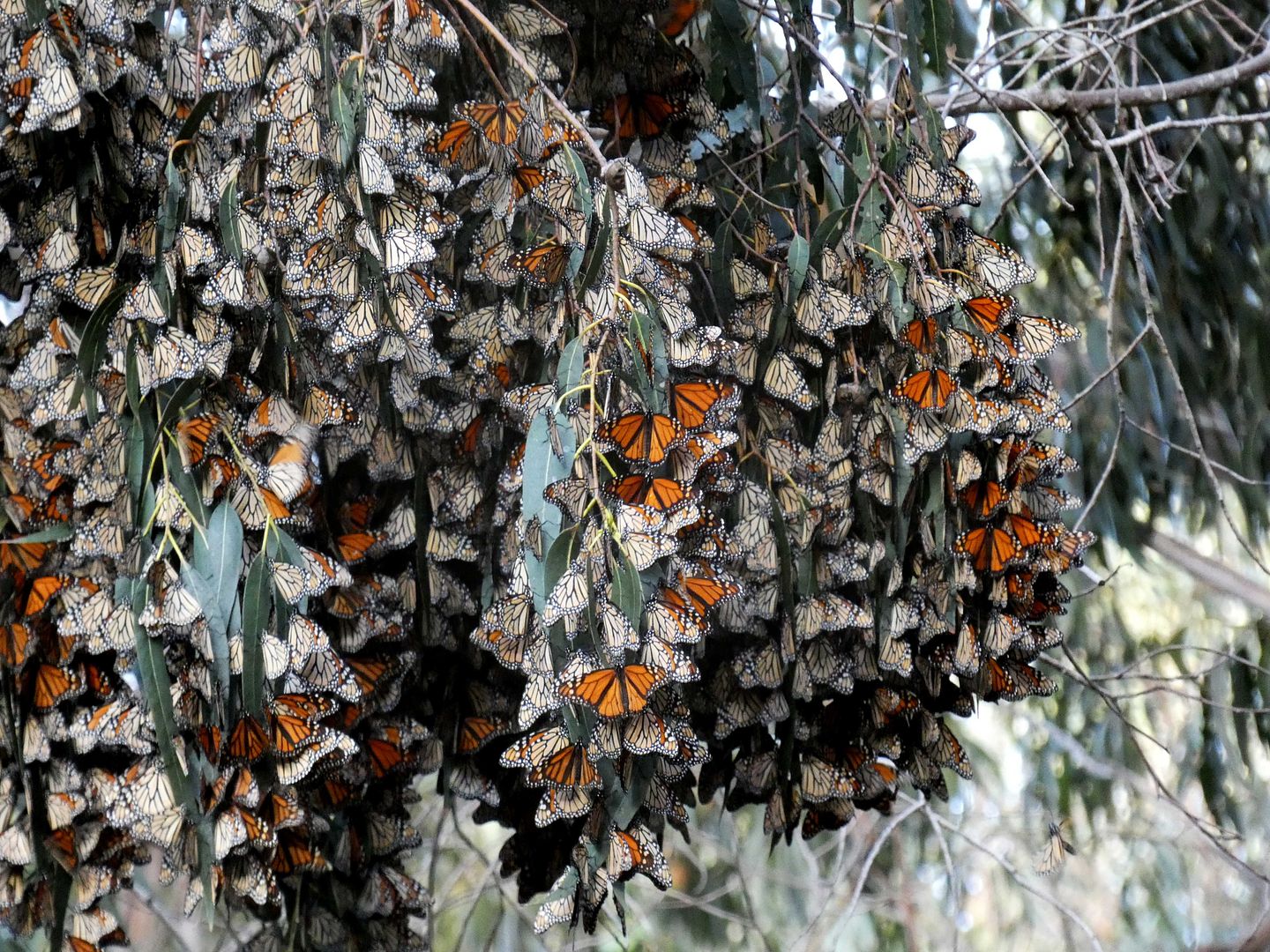

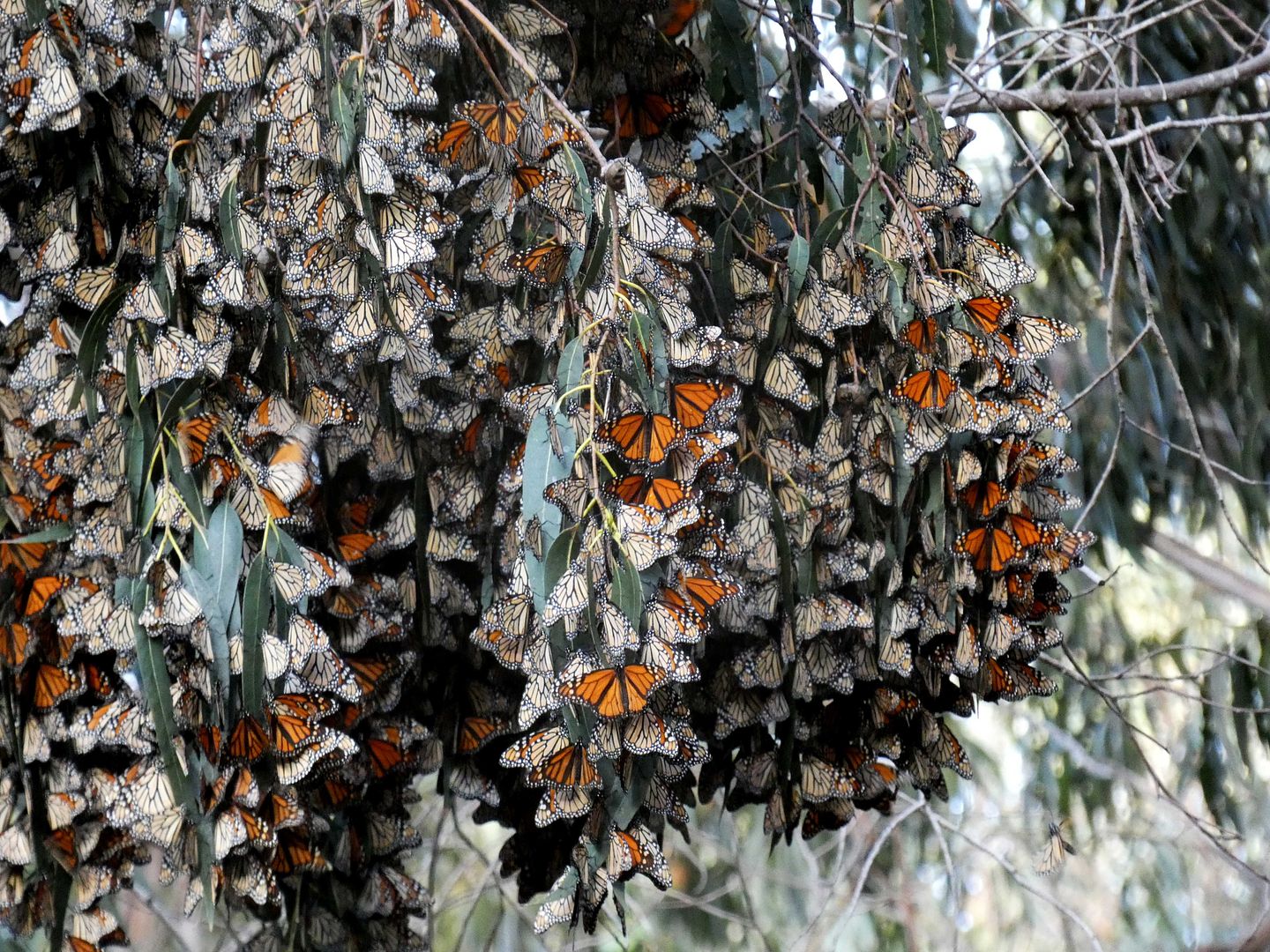

A crowd had formed along the paved path, and everybody was gazing up at one particular area of the eucalyptus trees. It was late in the afternoon on a December Saturday, when the sun would set around 4:45 and we had just about an hour's worth of daylight left.

It was the perfect time to see the monarchs clustering together in a roost as the temperatures began to dip—huddling with each other for warmth.

It was also still early enough—and with enough sunlight remaining—to see plenty of them still in flight.

In previous years, the reports had been dire. Official monarch counts saw numbers only in the dozens, not the thousands or tens of thousands (or hundreds of thousands) that used to occur during peak years.

But this year, I likely saw thousands. A recent official count tallied over 8,000 individuals, according to the SLO Tribune—still down from the 10,000 the grove (one of California's largest) has been known for, but up a lot from a recent year's count of just 2,000.

It made me so happy. I stayed much longer than I'd planned, just to see what they'd do—and to observe how the changing sunlight would make the roost look different.

Native migrating Western monarchs prefer non-native eucalyptus trees for their overwintering roost spots, gaining shelter and warmth and even nutrition from its nectar.

But when it comes to successful breeding, monarch caterpillars need to feed on native varieties of milkweed. When they can't find milkweed, the caterpillars can't metamorphose into an adult butterfly.

And since their lifespan could be as short as a couple of weeks, or as long as maybe 8 or 9 months, the population needs those babies to replace the adults that die off.

Fortunately, between last winter and so far this winter (though the season really runs October through February), we're seeing the highest numbers of monarchs that we have in decades. But nobody really knows why.

It could be weather, sure. But climate change and habitat loss are still major factors in the dwindling of monarch numbers since the 1980s and '90s.

At this point, I'll take what I can get. Especially because I know it may not last.

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment