If you know where to look, you can find remnants of California's Mission Period throughout the state—whether it's old dams and aqueducts, or even a former winery for communion wine.

And sometimes, you find an actual mission in the most unexpected of places—like the former Santa Margarita de Cortona Asistencia (founded 1787-90), which is hiding in plain sight in the now-privately-owned Santa Margarita Ranch in California's Central Coast.

Photo: Library of Congress (Public Domain)

Photo: Library of Congress (Public Domain)

.jpg)

Photo: Library of Congress (Public Domain)

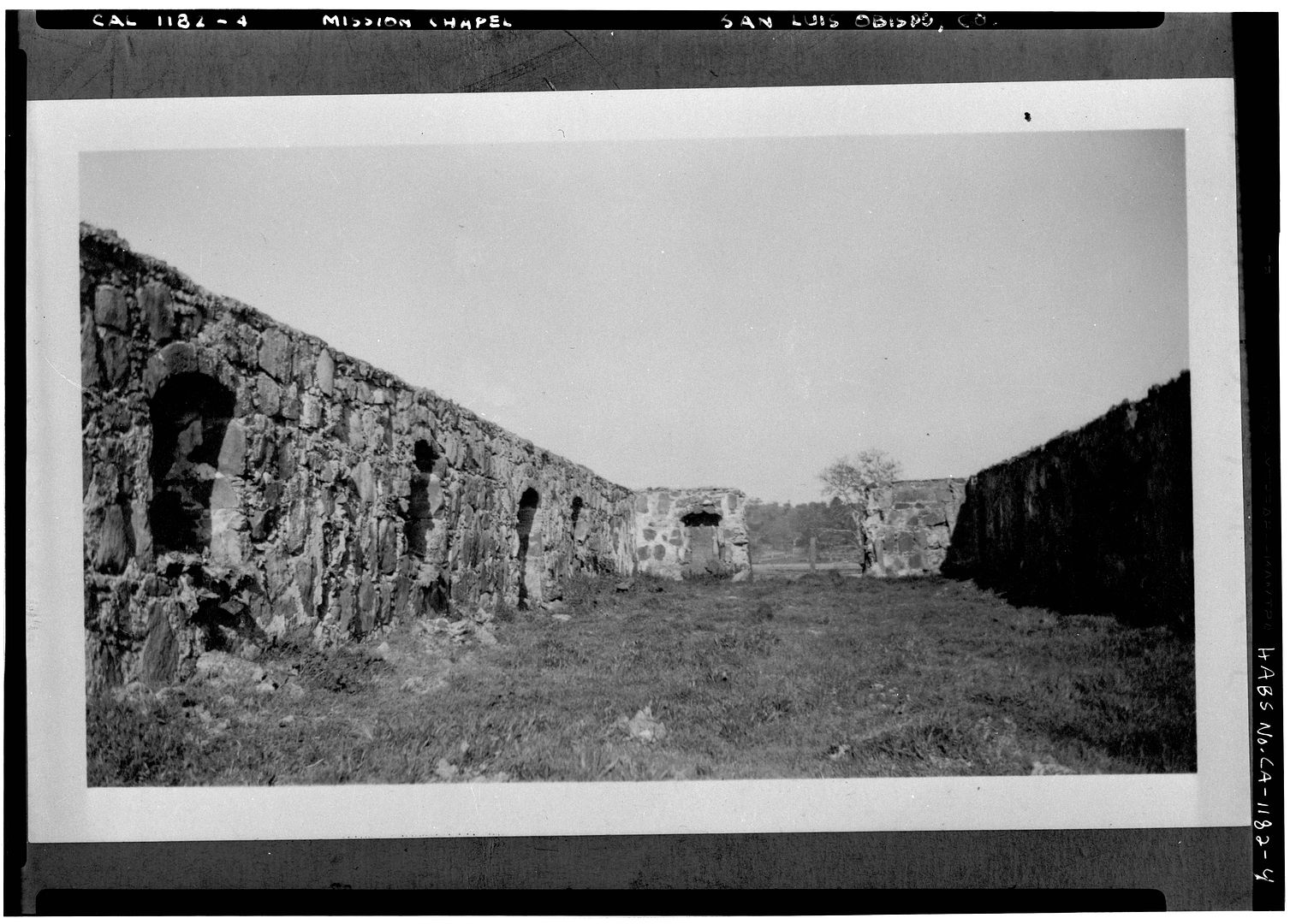

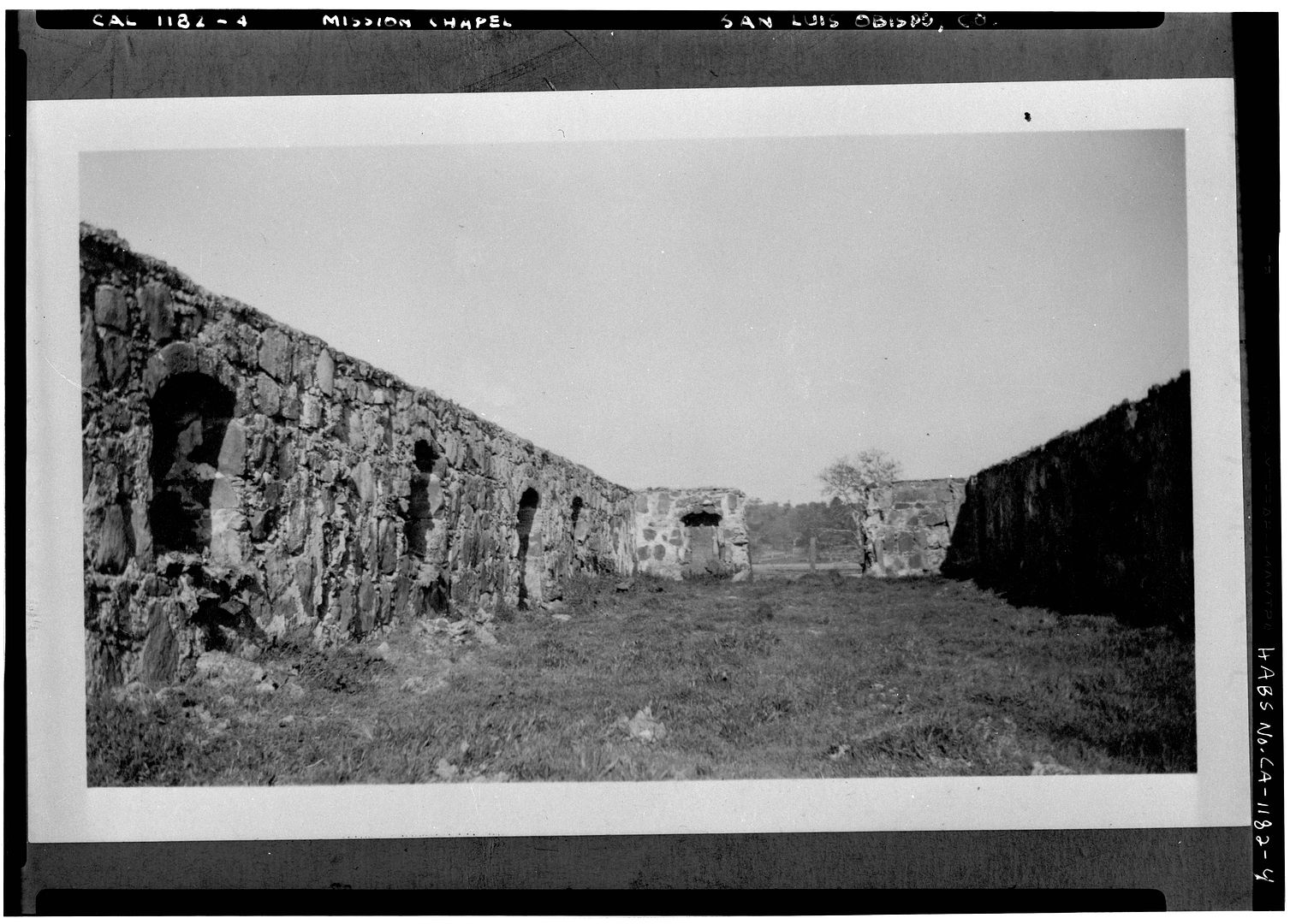

Photo: Library of Congress (Public Domain) It was actually an assistance mission (or sub-mission) of Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, which used it for agricultural purposes like raising pigs. All that's left of it now are the brick and stone walls that once enclosed it, dating back to 1817.

Fortunately, a barn superstructure was built (around 1904 to 1907?) to protect the historic site from the elements. Some historical accounts attribute that act to Paul W. ("P.W.") Murphy—a general in the California National Guard, who took over the ranch in the 1860s—but during that timeframe, the ranch was under the control of the Reis family.

.jpg)

Photo: Pierce, C.C. (Charles C.), 1861-1946, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons, California Historical Society Collection at the University of Southern California, USC Digital Libraries

According to the South County Historical Society, the original 120-by-20-foot building used to contain a chapel; a granary for storing mission crops like wheat (and, later, hay); and eight rooms for the head of the ranch, his servants, and visiting priests (since there was no resident priest, and many padres were making the trek along El Camino Real between the missions).

The open interior space is now used for events, like wedding receptions and "Christmas at the Ranch," despite the fact that its unreinforced masonry could take a tumble during seismic activity. (The interior walls were reportedly removed by pick and crowbar long ago.)

They were already seriously damaged in an 1830 earthquake—and their condition continued to degrade after the mission secularized in 1834 and granted to rancher Joachin Estrada in 1841. The Spanish tile roof may have already collapsed by then (perhaps around 1837). The entire thing was swept by multiple wildfires over the course of history.

However, the walls had been constructed under the direction of Padre Luis Antonio Martinez (likely using Indigenous labor) to withstand brute force—combining brick, sandstone, and fireproof mortar (made from locally-sourced oyster shells) into a kind of fortress.

Should those at the main mission closer to the coast be threatened by attack (by pirates or anything else, I suppose), it could serve as an "inland retreat" for those who needed to flee to safety.

Although functional, the walls were also decorative...

...particularly the archways and window openings, which each had their own ornamental patterns in the stonework.

Today, the barn is a nod to the current agricultural use of the present-day Santa Margarita Ranch, which is used for cattle grazing and grape-growing. (There was even a full sheep pen next to the barn during my visit.)

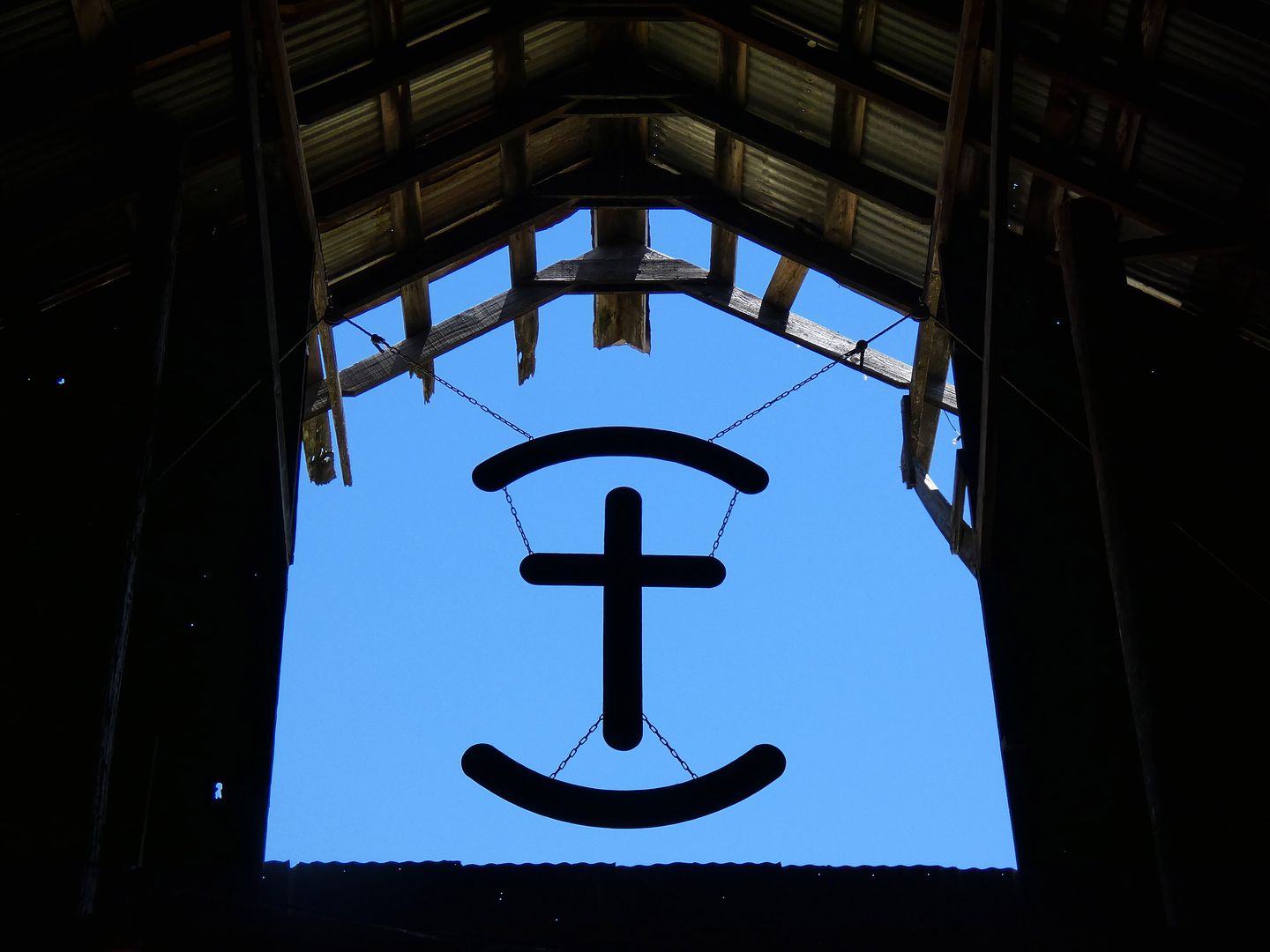

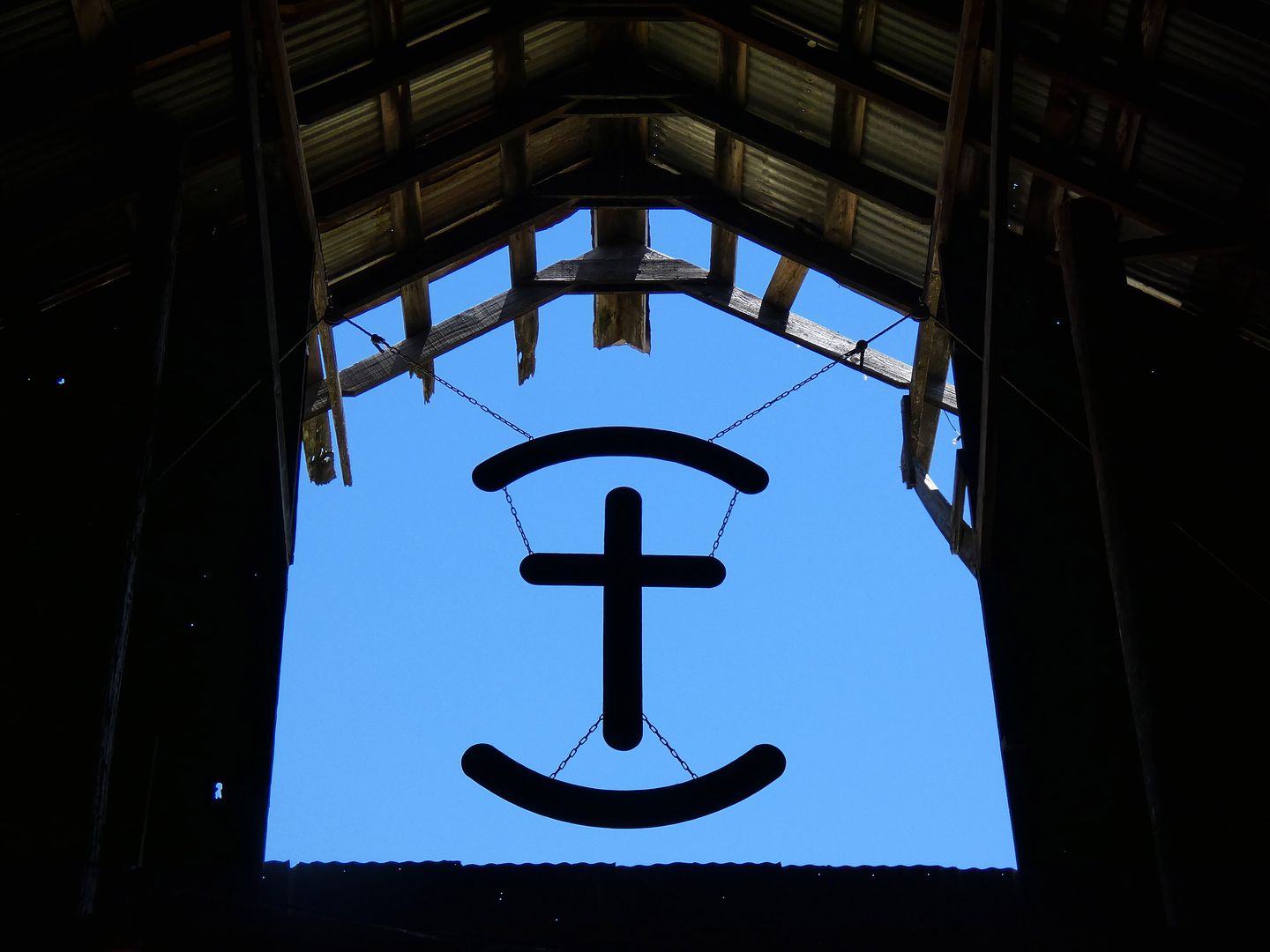

And although there is a cross hanging from the roof towards the back of the barn, that was added during the Rancho period—not the Mission period.

I'm actually really glad that this mission was preserved in place rather than being rebuilt like other California missions. In fact, it's seeing the earthquake-damaged chapel at Mission San Juan Capistrano that I treasure most, among all of the other replicas I've experienced.

Funny enough, even the hay barn itself has been rebuilt somewhat—originally constructed of corrugated sheet metal, and now reinforced with vertical wood siding. And although the barn is "new" compared to the mission that's hiding inside of it, it's still 120 years old and a major part of the ranch's history.

Lots more has been lost. Although the stone walls inside the barn have become known simply as the "asistencia," that was just the main building of the sub-mission—one that used to be surrounded by other buildings in an entire complex of small adobe houses and other support structures.

Today, the ranch has got a railroad, multiple wedding venues, private residences, Arabian horses, and more. But Santa Margarita Creek is still there—and the current ranch owners celebrate the hidden history within those barn walls.

Note that there's NO TRESPASSING on the property. The gates to the ranch are locked when it's not open for a public event.

The best way to see the barn (and ride the trains) is during the annual Best of the West Antiques Show, which takes place every Memorial Day weekend. (That's when I snapped these photos and began to learn the history from the South County Historical Society.)

Related Posts:

No comments:

Post a Comment